Abstracts

Here you will be able to view abstracts for all the conference presentations.

Thursday 1st July 2021 BST

National Museums Scotland Roundtable: “Images of the Buddha: Collecting Histories and the Displays of Buddhist Material in Public Museums”

Emma Martin (Chair), Friederike Voigt, Marjolein de Raat, Qin Cao, Karwin Cheung.

Research into the nature and the building of public and private collections has been an area of study for scholars and museum professionals for several decades. More recently, the collecting of objects from non-European and indigenous cultures in the context of national imperial histories has come to the front of public and academic discourse. In response, many museums have begun to reflect on how they represent imperial and colonial histories to their audiences and to make changes to displays and labels, broadening the narrative to tell a more nuanced story of their objects and how they came into their possession.

Provenance research addresses these complex issues of ownership and origin, networks and the value systems that have become attached to these items in the course of their colonial and post-colonial histories. This proposed roundtable panel would focus on the provenance issues particularly of Buddhist objects, and on how historical framings and current museum settings have constrained their interpretation and the understanding of their nature and sources. Four case studies will delve into selected object histories to uncover aspects of their social and political entanglements and bring nuance to the existing notions of how colonial collecting took place. The discussion following the presentation of the case studies will seek to understand how the identities and histories of Buddhist objects in museum collections and their transcultural roles can be used to address current issues of display, interpretation and public perceptions of Buddhist material culture. A summary of the presentations and the discussion points might be published in a blog.

Collecting and displaying Buddhist objects from South Asia at National Muse-ums Scotland (NMS) – Friederike Voigt, Principal Curator Middle East & South Asia

The multidisciplinary displays at Scotland’s national museum in Chambers Street fea-ture a substantial number of Buddhist objects, and particularly, small and larger-scale images of the Buddha. Although in different thematic galleries, they are primarily pre-sented as objects of art with a religious connotation, an interpretative approach that was established in the 1970s in Edinburgh with the exhibition ‘Asiatic Sculpture’. Re-search into the provenance of this ‘fine but little-known collection of Indian sculpture’, that was displayed on this occasion, shows that most of these images of Hindu and Buddhist deities were collected by Edinburgh’s learned societies between 1800 and 1830 rather than by NMS, or the Industrial Museum as it was originally known. Using a few key objects, I will trace the different meanings that Buddhist items in the collection have assumed in the course of their lives outside the context for which they were made – as subject matter of Orientalist and antiquarian interests, as examples of su-perior craftsmanship and as objects of art. Reinterpreting collections for contemporary audiences is an ongoing concern of museums and curators. How can the collecting history of these sculptures be used to inform their display and interpretation, challeng-ing existing conventions and addressing current issues?

Taking the Buddha out of Buddhism: provenance of two Japanese Buddhist statues – Marjolein de Raat, Japan Foundation Assistant Curator

National Museums Scotland have two large Buddhist sculptures in their collections: a statue of Amida Buddha that is on display in the Grand Gallery, and a statue of Sho-Kannon in the East Asia Gallery. Provenance research on these statues has shown that both were imported into the UK at the beginning of the 20th century and were used to decorate houses of the Scottish elite. However, while the Sho-Kannon was created for the Japanese Choshoji temple in 1787, research by Prof Kawai Masamoto of Keio University in 2013 suggests that the Amida Buddha was probably specifically produced for the export market in the late 19th century. This shows the Japanese agency involved in the export of Buddhist objects, and the creation and marketing of such items specifically for Western consumers.

The difference in origin invites reflection on how these statues are displayed and interpreted. Studying the provenance of these sculptures can give a more nuanced picture of how and why these Buddhist statues arrived in Europe. This will help to increase our understanding of the multitude of relations, networks and contacts involved in the trade in Buddhist materials. Distinction between the different origins will help to review our current notions on cultural appropriation and agency.

Yellow flag with dragon patterns – a Buddhist object with imperial associations in the National Museum of Scotland – Qin Cao, Curator: Chinese collection

Yuanmingyuan, also known as the Old Summer Palace, is infamous for its destruction by Anglo-French military forces in 1860. Numerous imperial objects were looted and subsequently dispersed throughout various public, private and royal collections outside China. These imperial Chinese collections had a significant impact on the perception of Chinese art in Europe in the 19th century, in contrast with the items produced for export that were available previously. In the last several decades, studies of high profile or well provenanced Yuanmingyuan objects have explored their biography, collecting contexts, artistic merits, and influences on decorative art.

Despite this, there are many museums across the UK with objects tentatively attributed a Yuanmingyuan or imperial provenance. Some undoubtedly deserve closer scrutiny to ascertain their identity and origins. Using a Buddhist flag with dragon patterns as a case study from the Chinese collection at the National Museum of Scotland, this presentation will present its provenance history of imperial associations when it entered the Museum in 1903. It intends to discuss the popularity of imperial objects in the UK since the looting of Yuanmingyuan from a post-colonial perspective.

Moving the immovable: Nezu Kaichirō and Buddhist sculptures from Tianlongshan – Karwin Cheung, Assistant Curator Asia

In 1937, the Japanese politician and industrial magnate Nezu Kaichirō (1860-1940) gifted a total of 19 Chinese Buddha heads dating from the Northern Qi (550-577) and Tang (618-907) dynasties from the cave temples of Tianlongshan to the governments of the Netherlands, Germany, Italy, and the United Kingdom. The majority of these sculptural fragments are today held in the various national museums of these respective countries.

Their removal from their original architectural and religious context was made possible through entanglements of cultural and international politics, the global art trade, and art history. By tracing the provenance of four heads, held today at the Dutch National Museum of World Cultures, I historicize the contexts through which these sculptural fragments moved. In addition, I consider the diverging ways in which museums have displayed these objects and recent developments in digitization.

Panel “Visions of Deities”

‘A Divine Vision on Earth: One Thousand Images of Kannon from Kōfukuji’- Yen-Yi Chan, Postdoctoral Fellow, Institute of Philology and History, Academia Sinica, Taiwan

The construction of one thousand images (sentaibutsu) of a single deity flourished in Japan in the second half of the Heian period (794-1185). This paper examines the one thousand wood statues of Shō Kannon (Āya Avalokiteśvara) from Kōfukuji in Nara, the tutelary temple of the Fujiwara clan. Dated to the twelfth century, this group of Kannon, also known as the Kōfukuji sentaibutsu, has received little scholarly attention. This is due to the fact that images from this set of the sentaibutsu are scattered around museums and private collections in Japan, Europe, and the United States. The construction of sentaibutsu may have been inspired by the images of Mañjuśrī and his retinue of ten thousand at Mt. Wutai in China, reflecting a craze for grandiose displays of accumulation of merit and manifestations of the buddhas in the past, present, and the future as described in scriptures such as Sutra of Buddha Names. By investigating the religious environment in which the Kōfukuji sentaibutsu were produced and rituals of chanting buddhas’ names, this paper elucidates the connection of this type of image ensemble to Pure Land belief, revealing that they were made to manifest visions of deities that were expected to appear through the performance of replications and repetition. In other words, the Kōfukuji sentaibutsu group was not intended to show an abstract realm of infinity, but rather a transformative scene that was within the reach of devotees—a vision of which would lead to salvation in Amida’s Pure Land.

‘Iconography and Efficacy of the Kannonkyō-ji Niō Ofuda’- Hillary Pedersen, Assistant Professor of Aesthetics and Art Theory, Doshisha University, Kyoto

Kannonkyō-ji, a Tendai Buddhist temple located in Chiba Prefecture in eastern Japan, houses a pair of late fourteenth-century Niō guardian sculptures inside its temple gate. These deities are featured on the numerous ofuda (printed talismans) that have been distributed by the temple since at least the mid-Edo period. Known for their efficacy in preventing fires and theft, they were typically placed in the entryways of businesses and residences. Focusing on a selection of nineteenth and early twentieth century ofuda distributed by the temple, along with accompanying narratives, this presentation will introduce the iconographic, stylistic, and textual changes in these objects over time. Emphasizing the connection between the printed medium and sacrality of ofuda in general, I demonstrate how the visual similarities between the Kannonkyō-ji ofuda and the Niō sculptures are secondary to their function and numinous power. Their efficacy is further enhanced by the inclusion of temple seals and the names of imperial family members and priests connected to the temple. In addition, the seemingly innocuous performance of placing these talismans in entryways extended the protective power of the Kannonkyō-ji Niō into new spaces via the two-dimensional depiction of the deities on the sanctified ofuda. These components functioned together to create a locus of Buddhist protection in secular spaces.

‘Saved by Kannon: Mourning, Memorials and Remembrance at Iwo Jima’ – Yui Suzuki, Affiliate Associate Professor of Japanese Art, Dept. of Art History and Archaeology, University of Maryland

The Battle of Iwo Jima (19.2.1945‑26.3.1945) is arguably the most recognized battle fought in the Pacific Rim and its legacy is firmly rooted in the collective memories of the American and Japanese people. Despite significant mass-media coverage on the battle, most people are unaware of the grim fact that even today, an estimated 10,000 Japanese soldiers remain unrecovered after more than 75 years.

Some of the earliest public monuments (ireihi) erected in memory of the Iwo Jima war dead were not secular memorials but Buddhist icons of worship: two Shō Kannon (Āryā Avalokiteśvara) statues (fig. 1- 3). Wachi Tsunezo, the founder of the Iwo Jima Association and an ordained Tendai Buddhist priest, installed the statues in 1952, when he accompanied a government mission to collect the remains of the dead soldiers. Wachi had the statues enshrined on carefully selected areas of the island and performed Buddhist mortuary services there. He also placed personal mementos (letters, poems, hair, photos) entrusted to him by the bereaved families inside one of the Kannon’s pedestals (fig.1). Over the decades, these two Kannon statues underwent dramatic vicissitudes of fate with one being stolen and the other given a new identity as a Buddhist-Christian “Maria Kannon,” as proclaimed by its pedestal inscription (fig. 2). This presentation will address the significance of Kannon on Iwo Jima and the reasons behind the dramatic conversion of the Shō Kannon statue, into a Buddhist-Christian amalgamate symbol of peace, in the context of public memorials honoring the war dead and acts of remembrance on the islands ravaged by the Pacific War.

Panel “Materiality”

‘A Deep Dive and Rare Resurrection of a Buddhist Bell’ – Sherry Fowler, Professor of Japanese Art History, University of Kansas

In 1822, a bronze temple bell was pulled from the ocean by a fisherman in Yokosuka, Japan. When a wooden plug that sealed the bell was broken open, two scrolls with the text of the Lotus sutra in remarkably good condition were revealed. More astoundingly, the bell and scrolls have inscriptions that explain they were sent to the bottom of the sea as an offering to the Dragon King’s palace by a monk-patron named Ryōshō in 1330. This paper will discuss why the bell was thrown into the sea and how combinations of performance and text worked to reconfigure the functions and perceptions of this bell and its sutras.

After surfacing from the sea, these treasures were given to Lord Matsudaira who deposited them in his storehouse and only showed them to curious peers. A year after the discovery, Matsuura Seizan described these treasures and their discovery within his series of essays. In 1857, the bell and scrolls came into the possession of Enshōji, a temple that faces Miura Bay where the bell was discovered, and become the subject of a woodblock printed text by temple abbot Myōnichi that told of their discovery and lengthy stay at the Dragon King’s undersea palace, as well as recast their origins from the perspective of Nichiren School Buddhism. For example, one of the scrolls was purported to be in Nichiren’s own hand. Now the bell functions as Enshōji’s main image of worship, dubbed “okanesama” with a reputation for improving health and money matters.

‘Embodied Objects: Chūjōhime’s Hair Embroideries and the Transformation of the Female Body’ – Carolyn Wargula, Visiting Assistant Professor of East Asian Art, William College

The female body in medieval Japanese Buddhist texts was characterized as unenlightened and inherently polluted. While previous scholarship has shown that female devotees did not simply accept and internalize this exclusionary ideology, we do not fully understand the many creative ways in which they resisted or sidestepped this discourse. One such method Japanese women used to expand their agency was through the creation of hair embroidered Buddhist images. Women bundled together and stitched their hair into the most sacred parts of the image—the deity’s hair or robes and Sanskrit seed-syllables—as a means to accrue merit for themselves or for a loved one. This paper focuses on a set of embroidered Japanese Buddhist images said to incorporate the hair of Chūjōhime (753?CE-781?CE), a legendary aristocratic woman credited with attaining enlightenment. I argue that temples promoted the veneration of such objects in the fifteenth century as a direct response to the popularization of The Blood Bowl Sutra. This apocryphal text produced in China during the eleventh or twelfth centuries emphasized the impurity of the female body due to menstruation. Chūjōhime’s hair embroideries served to show that women’s bodies could be transformed into miraculous materiality through corporeal devotional practices and served as evidence that women were capable of achieving enlightenment. This paper emphasizes materiality over iconography and practice over doctrine to explore new insights into Buddhist gendered ritual practices and draws together critical themes of embodiment, materiality, and agency in ways that resonate across cultures and time periods.

‘The Fifth Garden of Ryūgen-in’ – Amy McNair, Professor, Chinese Art History, University of Kansas

Five gardens surround the abbot’s quarters in Ryōgen-in, a sub-temple of Daitoku-ji, the Rinzai Zen temple in Kyoto. Four are included in every guidebook and tourist blog, yet the fifth is never discussed. The first is a tiny karesansui (dry rock garden) contained by the architecture. Alleged to represent a Zen saying, it was designed in 1958 by Nabeshima Gakusho. On the north side is a walled karesansui garden called Ryūgin-tei, or “The Roar of the Dragon.” The rock composition may represent the cosmic mountain Shumisen or a dragon rising from the sea. Purportedly, the shogunal painter Sōami designed it when the sub-temple was founded in 1502. On the south side is Isshidan, named after a sobriquet of Ryōgen-in’s founder, Tokei. Reconstructed in 1980, its rocks represent the mythical islands of the immortals. The fourth garden, Kodatei (or Hutuo River), is a narrow enclosed rectangle containing flat stones laid in concentric rings of gravel, said to represent the sounds “ah” and “om.” The fifth garden sits between the abbot’s quarters and the founder’s hall, unbounded and unmarked. Maps call it Keizokusan, the semi-legendary Mount Kukkutapāda in India, where Śakyamuni’s disciple Mahākāśyapa, esteemed as the founder of Zen Buddhism, dwells in suspended animation. Kukkutapāda is a site of unparalleled importance to Zen. Yet Keizokusan is just three small lumpy stones. Is it really a garden? Is it a Zen jest? Or a profound statement? Does it participate in Zen ideas of microcosm/macrocosm? Does it manifest a Zen aesthetic? Why doesn’t the temple explain it to visitors?

Roundtable “Aesthetics of Buddhist Belonging in/through Objects and Action”

Erica Baffelli and Paulina Kolata (Chairs), Trine Brox, Jane Caple, Gwendolyn Gillson, Levi McLaughlin, Frederik Schröer, Dominique Townsend, Elizabeth Williams-Oerberg

How do people craft, experience, and narrate Buddhist belonging through sound, smell, taste, touch, movement, and performance? How are belonging and Buddhist commu-nity formation transformed through time and space? Drawing from Buddhist contexts in China, Japan, India and Tibet, this roundtable will explore the generative and dis-ruptive force of affects that circulate through words, images, objects, bodies, and per-formances to guide our understanding of how Buddhism is done. Informed both by ethnographic and textual research, our discussions approach the notion of aesthetics as sensorial processes of meaning-and-value-making (rather than in the narrow sense of beauty), asking not only how Buddhism feels but how Buddhist belonging is gener-ated through the affective labour involved in and around rituals, scriptures, statues, food, and music (among others). By exploring such aesthetic practices, we will open up a discussion about how affective bonds and emotions shape Buddhist adherents’ material practices and existential concerns relating to, for example, individual and col-lective temporalities. In particular, our focus on aesthetics and emotions, and the con-nections they enable and disable, will allow us to explore how notions of authenticity are constructed, negotiated, and contested in the everyday by a wide range of Buddhist actors. This roundtable will present reflections and case studies that emerged from an annual seminar on “The Aesthetics of Religious Belonging,” hosted by the University of Copenhagen and The University of Manchester, inviting other conference partici-pants to join the conversation on how aesthetic and emotional forms and practices transform Buddhist institutions and individual senses of belonging.

Organizers: Erica Baffelli, The University of Manchester and Paulina Kolata, Man-chester Metropolitan University

Participants: Trine Brox, University of Copenhagen: Buddhist objects, commodification and authen-ticity in Chengdu, China.

Jane Caple, Independent Scholar: Everyday aesthetics of belonging in monastic-lay communities in Tibet.

Gwendolyn Gillson, Illinois College: Food and Pure Land Buddhism in contemporary Japan.

Levi McLaughlin, North Carolina State University: Music and Soka Gakkai in Japan.

Frederik Schröer, Free University of Berlin: Absence and Tibetan diasporic community formation in India.

Dominique Townsend, Bard College: Autobiographical Treasure narratives in Tibetan Buddhism.

Elizabeth Williams-Oerberg, University of Copenhagen: Buddhist rituals and media performances in Ladakh, India.

Roundtable “Decolonisation and Buddhist Studies”

Alice Collett (Chair), Daud Ali, Elizabeth Harris, Salila Kulshreshta, Patrice Ladwig

In the current UK academic environment, moves to decolonise the curriculum are growing. Presently, around one fifth of UK universities have an expressed aim to make efforts to decolonise their curricula. In this environment, for Buddhist studies scholars – historians, archaeologists, anthropologists – it seems apposite to pose the question afresh, “Should we use the work of colonial scholars and colonial archaeologists to help us understand the history of Buddhism and the history of Asia?” In this roundtable discussion, six scholars from around the globe offer short presentations relating to this question. These presentations will be followed by a thirty-minute roundtable discussion which will then open to questions. The theme of the conference is ‘Word, Image, Object, Performance’ and different aspects of this theme will be taken up by panellists. What if, for instance, you are trying to translate a difficult word and the translation of a colonial scholar helps you to understand the passage? What if a colonial archaeologist photographed and published an image of an inscription that had now eroded away when you revisit the site a hundred years later to photograph anew? Or what if a colonial art historian had published the only photograph of an artefact now lost? Panellists may focus on certain countries, such as Sri Lanka or Laos, or on disciplines, such as archaeology or museology.

Panellists: Daud Ali (University of Pennsylvania), Elizabeth Harris (University of Birmingham), Salila Kulshreshtha (NYU Abu Dhabi), Patrice Ladwig (Max-Planck-Institute)

Friday 2nd July 2021 BST

Roundtable “Buddhist Materialities in Premodern Japan”

Cynthea J. Bogel (chair), Miriam Chusid, Michael Como, Hank Glassman

Roundtable description

This roundtable brings together scholars of premodern Japan to discuss our research on Buddhist materialities of object, word, image and concept across the disciplines of Buddhist studies, art history, and religious history. It will consider the state of research in these fields today; raise questions about the nature and complexities of materiality in Buddhist objects, icons, and texts; and consider what new understandings can arise by foregrounding this approach when studying and teaching a vast range of artefacts, manuscripts, and rituals, including ones where the material dimension has not been previously considered. We cannot hope to define materiality across diverse regions and time periods, practitioners and practices, but we offer the roundtable as a corral within which to isolate dynamic models of inquiry. Each panelist will open with remarks on a specific topic that interrogates the question of Buddhist materialities, followed by a panelist discussion about points of mutual interest within the presentations, integrating and ending with audience participation.

Miriam Chusid (University of Washington)

The remains of Oikawa Zen’emon’s deceased wife rest in a painting at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The composition, which depicts the Buddha’s welcoming descent to greet the newly dead, bears fragments of ash from this seventeenth-century woman. A representation of her likeness is also found in the painting; she is depicted sitting with her hands in prayer in the bottom right corner awaiting the Buddha’s arrival. The inclusion of this woman’s portrait, along with her physical body, perpetually places her in the Buddha’s embrace and merges her memory with the divine. In this talk, I will offer reflections on the nature of Buddhist materiality by examining the relationship between corporeal relic veneration and portraiture, and by considering how the act of emplacing Mrs. Oikawa’s remains inside a painting served to recover her memory every time the object is displayed.

Hank Glassman (Haverford College)

That Buddhism puts great emphasis on the impermanent nature of life, and especially on the frailty and unreliability of the human body, goes without saying. And yet, in the creation of the gorintō in early medieval Japan and its increasingly widespread adoption as a grave marker in the centuries following, we see an attempt to create an adamantine, changeless stand-in for the human body. In the interplay between permanent stone monuments marking the corporate family and ephemeral wooden elements commemorating the deaths of its individual members, we can find in the iconography of the Japanese grave a fruitful ambivalence towards bodies, families, salvation, and the passage of time.

Cynthea J. Bogel (Kyushu University)

Scholarly discussions of large-scale 3D buddha icons typically feature the represented body of the divinity and its iconography. Para-sculptural components such as the pedestal, nimbus, and canopy, however, hold a dynamic space together with the buddha figure and generate meanings, form, and visual dynamism in the temple hall. Conceptual or visual strategies not easily expressed in the sculpted buddha-body component may be expressed in the para-icon components; these may include narrative, comparison, elaborate signification and symbolism, color, and even text. These para-sculptural forms convey something akin to “the before-the-buddha,” “the becoming-the-buddha,” or” the paradise of the buddha,” notions more dynamic than the terms “Buddhist iconography” or “attribute” typically convey. And more: I will highlight a few early surviving Japanese icon pedestals (7th to mid 8th c.) and consider an emerging Japanese imperium’s self-representation and the “galactic polity” (S. Tambiah) inherent in Mt. Sumeru representations. The pedestals of this period, in particular, offer a window to understanding more about the worldviews and beliefs of the viewer/patron of the day.

Michael Como (Columbia University)

When during the 7thcentury the Buddhist tradition first began to proliferate within the Japanese islands, there was virtually no basis for the Buddhist material and textual culture that had developed across East Asia during the previous half millennium. As a result, managing the development of technologies and material resources necessary for the production of temples, icons and texts became a central concern for Japanese Buddhists for centuries thereafter. Concurrent with these developments, archeological evidence from the 8th-and 9thcenturies has also established that this period also witnessed the developed of new, entextualized ritual media for the engagement of the super-human world such as small human effigies or scapegoat dolls (hitogata), spell-bearing wooden tablets (mokkan), and clay pottery (bokusho doki). In my talk, I will discuss how these entextualized objects, when read together with such texts as the Nihon ryōiki, shed invaluable light on non-elite as well as elite Buddhist strategies for securing benefits both in this world and in the afterlife.

Panel “Illustrated Manuscripts”

‘Searching for Images of Protectors with Sacred Script’ – Anne Bancroft, Senior Book & Paper Conservator V&A Museum

This short paper discusses an interesting quest, of an initially in-house technical analysis project on nagthangs that lead to an exciting discovery of a group. The date, the group consists of a refuge tree and four protectors spread across three museums in different countries. It is a detailed examination of the least studied of the Vajrayana Buddhist array within the context of the wider historical and religious origins. How were they commissioned, made, the materials used, their use, and how they came to be in museums. A range of scientific analysis was carried out focusing mainly on the painted element. This original research has joined objects that were disassociated and reconnected through understanding the fabrication of the images, the inscriptions, dedicatory texts and how these deities perform in their duties. The findings have added to the knowledge of commissioning nagthangs. On four of the nagthangs it has tighten the dating because of the discovery of the artist Kyenrab Jamyang (1650-1700) and the benefactor Manga Ratna. It is now known that these are of the Sakya and Lama Butön Rinchen Drup lineage. (1290–1364), 11th Abbot of Shalu Monastery.

There will be an explication of the methodology and findings that combines technical art history and iconography. It advocates the merits of provenance files, the fortuitous leads to be found in old exhibition catalogues deciphering secret and sacred iconography and text. Given the increase in exhibitions focusing on Buddhist and tantric art it is of intrinsic and topical interest.

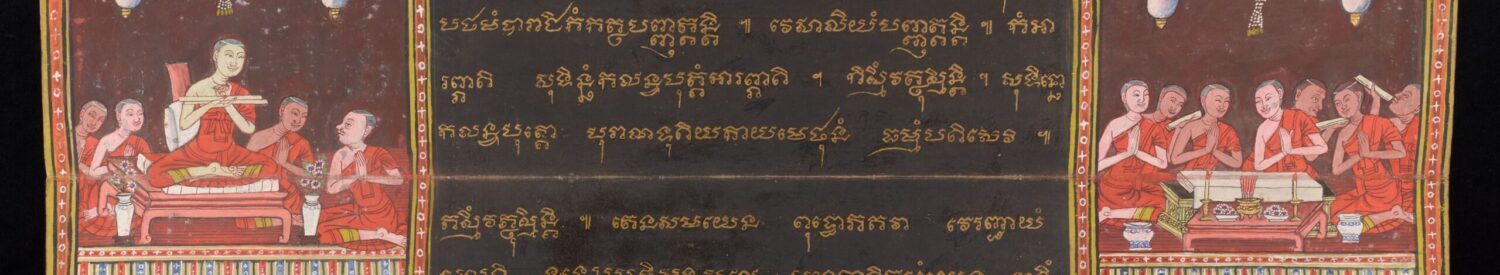

‘Illustrated YogāvacāraManuals from the Khmer, Thai and Lao Buddhist Traditions’ – Jana Igunma, Ginsburg Curator for Thai, Lao and Cambodian Collections, British Library

Yogāvacara practice was an integral part of Theravāda Buddhism in Southeast Asia until monastic reforms of the 19th century discouraged these practices. Focusing on meditation, Yogāvacara manuals incorporate teachings from canonical as well as post-canonical literature: for example, the Navasivathikapabbaṃ (Nine charnel-ground observations) of the Mahāsatipaṭṭhānasutta as well as Buddhaghoṣa’s explanation in the Visuddhimagga on meditation on the foul are reflected in the Sinhalese “Yogavacara’s manual of Indian mysticism as practised by Buddhists” examined by Rhys-Davids (1896). Illustrated Yogāvacara manuals from the 18th and 19th centuries found in Southeast Asian Buddhist traditions highlight meditation practices including contemplation of core Buddhist teachings like dependent origination, four attachments, three marks of existence, contemplation of the decaying corpse, the fruits of entering the stream, saṃsāra and nibbāna etc. Three such illustrated manuals will be introduced in this paper: one fragmented example from the 18th-century Khmer tradition, and two 19th-century manuscripts from the Thai and Lao traditions. While it is thought that the Sinhalese version is a copy of – or was strongly influenced by – an older Thai version brought to Sri Lanka when the Siam Nikāya was established there (1753), the three manuscripts give insight into Southeast Asian Yogāvacara meditation practices, and how knowledge about these practices may have been disseminated in form of graphic images rather than text.

‘Walking Meditation in a Painted Landscape Scroll’ – Elizabeth Kindall, Director of Graduate Studies, Associate Professor, Department of Art History University of St. Thomas

This presentation will examine the reception of the somatic elements of a unique scroll of painting and poetry depicting the Yandang mountain range, just south of Hangzhou, China. I argue these elements allowed viewers to transcend “armchair travel” through the scroll to engage in “walking meditation” and “seated meditation.” The Yandang scroll, made by the government official Li Zixiao in 1316, combines his paintings of monasteries, topographical forms, and Buddhist icons with prose and poetry inscriptions that immerse viewers in a visual and literary journey into the multi-sensory experiences of the mountains. Later viewers, such as Zhu Jian (1462-1541), responded accordingly with colophons they added to the scroll. I will first examine the sensorial and apperceptive reports of travelers found in the topographical, historic, and literary traditions recorded by Zhu Jian in his Yandang Mountains Gazetteer. I will then explore how the style and structure of the scroll encouraged viewers to imagine they had been transported to the range physically, enabling them to perceive the somatic elements of a journey there. I will conclude by arguing that Zhu Jian’s reception of the Yandang scroll was intentionally mediated through his senses, as part of his beholder’s share. In this way, a knowledgeable and experienced viewer like Zhu Jian might physically immerse himself in the topography of the site, a necessary requirement for those who wished to engage in the practice of seated or walking meditation in the painting.

Panel “Fragments and Calligraphy”

‘Material and Immaterial Transformations: Thoughts on Sūtra Fragments in Tekagami’- Edward Kamens, Sumitomo Professor of Japanese Studies, East Asian Languages and Literatures, Yale University

Of the 139 calligraphy specimens in the “Tekagamijō” album (Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University), only four—and possibly a fifth—are fragments of sūtras: this is far fewer than in other albums of a similar kind and quality: for example, the Kyoto National Museum’s “Moshiogusa” tekagami has at least 32 shakyō dankan out of 242 total specimens, and the Idemitsu Museum’s “Minu yo no tomo” tekagami has 36 shakyō dankan out of 229 specimens. The first specimens in all of these albums (and many others like them) are presented as writings in the hand of Shōmu Tennō and of his consort Kōmyō Kōgō, but shakyō dankan attributed to writers in other social strata are included as well. In this presentation, I will focus on the examples of sūtra fragments in the “Tekagamijō” to consider their place and function within the larger schema of tekagami as such. How are the nature and the cultural significance of sūtra copies changed, materially and immaterially, when they are cut up, dispersed, and their parts then reused in tekagami? What is the meaning of these transformations?

The “Tekagamijō” is one of several such albums that are the subject of increased scholarly scrutiny. In addition to the collection of metadata on this album’s content (see The Tegakamijō Project), I am interested in thinking about how the constituent parts of tekagami produce meaning through their collective interaction and arrangement. In that connection, this presentation will delve into the Buddhist material and textual aspects of “tekagami culture.”

‘Burning Still: Calligraphy Collecting and the Appreciation of “Burnt Sūtra”’ – Akiko Walley, Maude I. Kerns Associate Professor of Japanese Art, Department of the History of Art and Architecture, University of Oregon

On the fourteenth day of the second month, 1667, a fire broke out in the Nigatsu-dō Hall at Tōdaiji, Nara prefecture. A set of eight-century handscrolls with the Flower Ornament Sutra done in silver ink on lush indigo-dyed paper was salvaged from its wreckage but with significant damage. The temple preserved the half-burnt sutra, remounting them onto a new backing paper. These so-called “burnt sutra” (yakegyō 焼経) with mesmerizing wave-like scorch pattern became collectables among tea practitioners and calligraphy afficionado. In order to mount them as hanging scrolls or paste them into calligraphy albums (tekagami 手鑑), these damaged sutras had to be cut further but in a way to carefully preserve the brutal marks of the initial fragmentation caused by fire. Adopting Susan Stewart’s observation concerning the two speeds of ruination, “furious” and “slow,” this presentation considers the symbolic implications of the double fragmentation we observe in the appreciation of yakegyō. It will argue that while the burn marks had the effect of accentuating the simultaneous presence and absence of the Buddha’s words, the fact that the scrolls were fragmented twice sheds light on how people during the Edo period might have perceived the act of cutting calligraphy for collecting and exhibiting. In the collectors’ minds, the fragmentation for collecting may not have appeared as an act of destruction or a violent dislocation of the part from the whole, but instead an act sanctioned by the perceived indestructability of the idea of wholeness.

‘Fujiwara no Toshinori, Shinjaku, Master of Words and Images’ – Michael Jamentz, University of Kyoto

The mid-ranking aristocrat Fujiwara no Toshinori, has largely been forgotten, but in his own day, he was seen as rivaling the most celebrated scholars of the Heian period, Sugawara no Michizane and Ōe no Masafusa. In this paper, I demonstrate that Toshinori, whose Buddhist name was Shinjaku, composed the text of the national-treasure Heike nōkyō ganmon, which has usually been attributed to Taira no Kiyomori. First, I establish that Toshinori was a prolific and accomplished author of this genre of kanbun literature, which required skill in creating elaborate couplets and a profound knowledge of Buddhism and Chinese history. After documenting the existence of many, overlooked works written by Toshinori, including those composed for Ike no Zenni, the stepmother of Kiyomori, who some postulate was the driving force behind the creation of the Heike nōkyō, I demonstrate that passages from the ganmon can be found in generally neglected works, proving that the ganmon was authored by Toshinori.

Toshinori thus played a leading role in the recreation of one of the most striking examples of the artistic amalgam of words and pictures created in the 12th century. His contribution echoes the accomplishments of other members of his immediate family, who are thought to have been involved in the creation of landmark pictorial works such as the Kunōjikyō, Gensōtei e, and the Genji monogatari emaki, as well as various collections of Buddhist iconography. Toshinori’s role in producing emaki for the imperial court is precisely analogous to that of his brother, the monk Jōken, who produced the Go-Sannen gassen emaki for Retired Emperor Goshirakawa.

Roundtable “Performing scripture: Text Meets Art, Music and Drama”

Eviatar Shulman (Chair), Pia Brancaccio, Natalie Gummer, Trent Walker

This roundtable panel aims to bring together a number of relevant perspectives for the assessment of the performative nature of Buddhist scripture, mainly in relation to the category of Sutta/Sūtra. Together the presentation will join in suggesting that in order to understand the idea of scripture at work in the (relatively-) early Buddhist world, we must approach the performative dimensions of these texts in a much more confident way than is currently prevalent in scholarship. The “meaning” of these texts, in their indigenous contexts, is couched more in their emotive, aesthetic, sonic, sensual, somatic, dramatic, and visionary contents, than in any doctrinal content they may convey. Again, and in new ways, we must learn to bracket our Protestant instincts, and allow philosophy to connect with these more concrete and embodied dimensions.

In the first presentation, Eviatar Shulman will address the question of “What is Recitation? Between Text and Performance”, in which he will share his experiences as an emerging Saṃyutta-bhāṇaka, emphasizing the importance of rhythm and prosody to memorization, recitation, and to the very meaning of the texts. Thus, the supposedly meaningless particles as kho or kho pana often convey the key meanings of a discourse. Next, Pia Brancaccio will speak of “Art and Performance in the Buddhist Visual Narratives of Bhārhut”, highlighting how the depictions of the Buddha’s life at Bhārhut are connected to a tradition of Buddhist recitation, local storytelling and performance. In the following talk, “Buddhahood as Performance Art: Normativity, Performativity, and Impersonation on the Bodhisattva Path”, Natalie Gummer will demonstrate that the path to Buddhahood envisioned in some Mahāyāna sūtras entails embodying and enacting buddha-speech in the manner of an actor learning a part—but with the difference that one is attempting to become that part. Finally, Trent Walker will address musical dimensions of the texts by speaking of “Pali-Vernacular Bitexts in Performance: Language, Phrasing, and Melody”, and showing how Pali and vernacular Buddhist texts are recited with a wide range of melodies and vocal styles in Cambodia, Thailand, and Laos.

Comments are closed

Comments to this thread have been closed by the post author or by an administrator.