Director Jane Campion regularly champions female protagonists in her work, situating her characters, such as Ada McGrath (The Piano, 1993), Frannie Avery (In The Cut, 2003), or Robin Griffin (Top of the Lake, 2013) in hostile environments.

In each of her cinematic worlds, Campion’s female protagonists battle to have their voices heard (quite literally, in Ada’s case) above the clamour of those of her male characters. This time, by keeping the focus squarely on her women however, Campion manages to tell their stories, without necessarily channeling them through the viewpoint of their male counterparts.

Her most recent film, Academy Award nominated The Power of the Dog (2021), gently unfolds the story about Burbank brothers, the wealthy ranchers in Montana. After his brother brings home his newly married wife, Phil Burbank (Benedict Cumberbatch) finds himself exposed to the possibility of love with this woman’s son. In The Power of the Dog, Campion and cinematographer Ari Wegner instead focus on male protagonists negotiating their own inhospitable surroundings. The sole female lead, Rose (Kirsten Dunst), is still the victim of cruelty dealt out by her new brother-in-law and she undeniably suffers. Nevertheless, Rose’s story is secondary to that playing out between three men – Rose’s new husband George (Jesse Plemons), her brother-in-law Phil, and her son Peter (Kodi Smit-McPhee). In shifting this focus towards a male narrative, Campion is able to do something different. She deliberately desexualizes Rose (and the few other peripheral female characters) and concentrates on the male body, ultimately leading the film to imagine a broad, inclusive audience.

In cinematic terms, the male gaze refers to the sexual positioning of women, whereby their bodies are objectivized and fetishized specifically for the pleasure of the supposed male viewer. The female gaze on the other hand is not simply a reversal of this power dynamic, where a supposed female viewer fetishizes the male body, but is more concerned with the agency of that onscreen female body.

The Power of the Dog refuses to fetishize Rose. She reminisces about being praised in school as a child for her schoolwork and for her beauty. In this, she admits that her self worth is tied up with how others see her. Look, however, at how Campion presents Rose, not as an object, desired and praised by others but choosing instead to dress her in shapeless clothes and present her with limp, flyaway hair. She is ordinarily without make up on her red and wind-chafed face. Even on the occasions when she does dress up (her wedding, meeting George’s parents) she can’t be described as glamorous, with only a smear of lipstick and an inexpertly pin-curled hairstyle. Campion simply does not permit the sexualization of Rose – even George’s courtship of her is more soulful than sexual, placing emphasis firmly on his gentleness rather than her desirability.

In place of this fetishization however, Rose is not granted agency. She may be financially more secure as George’s wife, but she cannot control her surroundings or any perceived threat to herself and her son. Campion is not therefore presenting an exclusively female gaze. What she instead chooses to do is to deny an exclusively male or female gaze in favour of a sensitive and tender examination of the male body, where nakedness is not lascivious but beautiful, not seedy but appreciated. In revealing men as vulnerable and gentle, she imagines a quieter and more reflective form of masculinity.

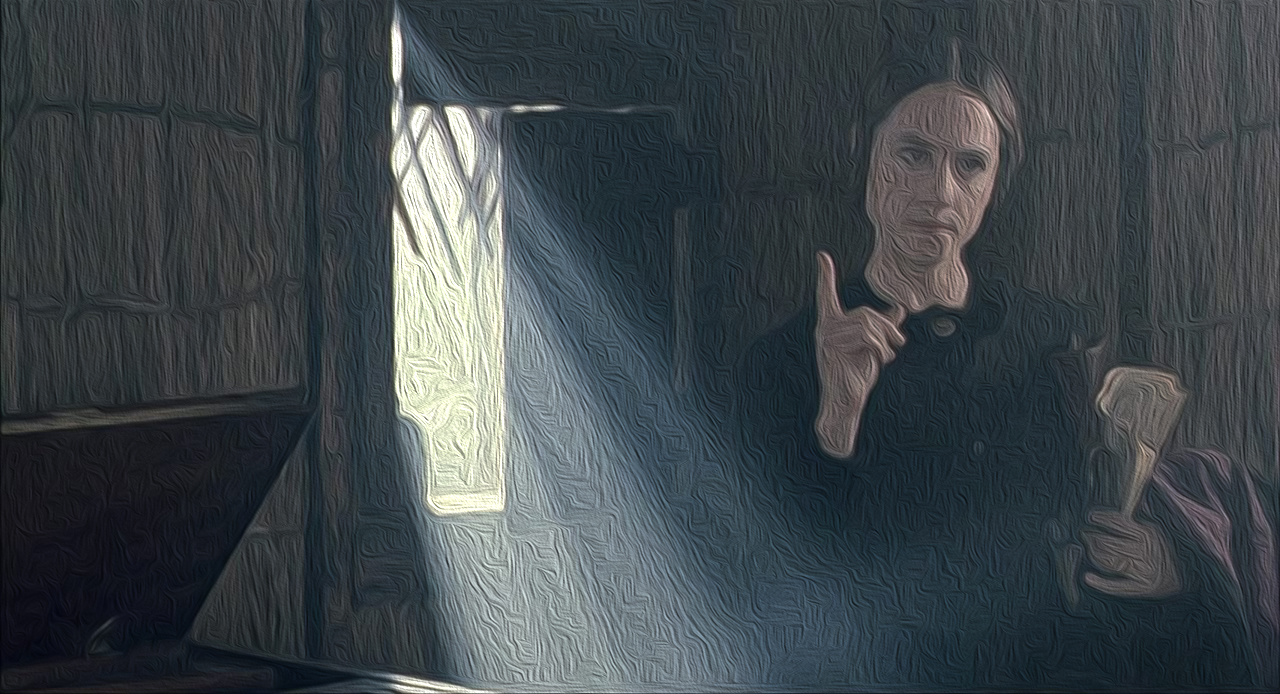

Several times during the film, Campion frames the most recognizable image from hyper-masculine Ford westerns – a sole male figure silhouetted in a doorway. This signals traditional masculinity – singular, powerful, rugged. In direct contrast however, Campion presents a joyful sequence of the cowhands as they bathe together in the river after a dusty cattle roundup. The bathing men are not to be salivated over, but appreciated, like a marble Florentine sculpture. Yes, the gaze here can still be read as voyeuristic but it is not in order to disempower the object, instead it is imbued with tenderness, as the cowhands wash the dust and grime from their bodies and lie down on the riverbank. Phil rides away to be alone and in the sequence that follows, his body is filmed with care and tenderness. He removes his shirt and kneels down, as dust motes swirl around him. Removing a scarf from his pack, he gently caresses his torso with it. Wegner’s lighting softly filters through the scarf, emphasizing its softness and delicacy juxtaposed against Phil’s taut muscles, as it drifts through his fingers. The camera is patient, lingering on his body as every inch is stroked, caressed, and appreciated. In these shots, Phil’s gloveless hands are examined in close-up, again suggesting the Florentine marbles and inviting the viewer to enjoy their beauty and form, without objectification. Johnny Greenwood’s score heightens the solemnity of the sequence, connecting the images to other valued arts such as classical music, and detracting from any objectifying gaze.

These scenes can be appreciated by women and men, straight and queer, but not as a site for sexual titillation. Something else happens here – an appreciation of the male body as a site of tenderness and value. In doing this, Campion and Wegner rid the screen of the power imbalance always at play through the male gaze. This in turn allows for a wider audience: women can enjoy the scenes of male nudity without being disempowered and queer men can enjoy them without feeling othered. Indeed, these scenes speak directly to a universal pleasure in and appreciation of beauty and, in this film, the gaze extends beyond gender.

Does it necessarily take a female creative team to achieve this? Perhaps not. It is notable that both Campion and Wegner have both been recognized by the Academy – a notorious boys club – for their work. Nevertheless, the determination of their artistic vision to avoid the genre norms of the Western has successfully produced a film of great emotional power, which speaks to a desire and need for inclusive texts that can reach the widest possible audience. The film’s potential success at the Academy Awards ceremony at the end of March will establish whether their universal gaze is appreciated by their peers.

Written for The Film Dispatch by Lesley Finn