In Park Chan Wook’s Oldboy, memory seems to be a way of navigating a mystifying present. Ethan Radus argues that in remembering something we do not transport ourselves into a fixed history so much as we begin to reckon with our present day lives.

Often, we subjugate the present to the past, and memory assists us in this operation. The present is pre-determined, lacks affective complexity, and can be rationally explained. The past is oneiric, transcendent, and feels visceral to us. It is emotion heightened beyond the bounds of what we could possibly feel now, always far better or worse than what we experience in the moment. Memory thus taunts the cold, banal present with sepia-toned warmth, with sights and sounds that seem lost or archaic, stuck in the context of their origin, never again to be felt or experienced. The past is poetic and beautiful, while the present is prosaic and boring. But why is memory an abstracted version of reality and not reality itself? Perhaps it isn’t an agent of the past either, quietly acting on us as we stare blankly at our unfolding lives. Instead, maybe it is simply the word we use for our inability to understand our confusing lived experience: memories helping us to reckon with (and decipher) our present, not retreat from it.

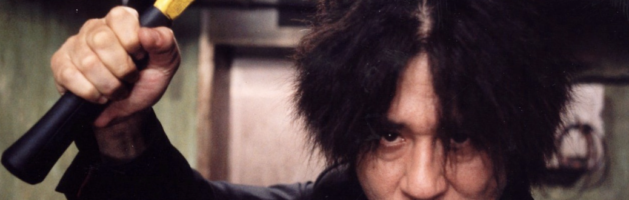

Oldboy is a film about a man who does not remember something he has done that is insignificant to him, but extremely important to somebody else. For this, he is sentenced to 15 years abduction and imprisonment, wherein he is incarcerated in a hotel room with only a television for company. Upon release, he is an entirely different man. Woozy drunkenness has metamorphosed into wizened insanity, pathetic grumbling into a silent, animalistic violence. His initially diminutive physicality has been shed, leaving an arched, hulking strength. We do not know why Oh Dae-su was imprisoned and, like him, we are trying to figure this out. As our protagonist sifts through his memory for clues, we intuitively hunt and collate them too, exercising our own faculties of memory over the course of the film.

Memory is therefore the fundamental engine of narrative. Once released, Dae-su is given 5 days to work out his wrongdoing, lest he be punished once again. The story recalls Kafka’s The Trial, in which an innocuous clerk is approached unexpectedly by government officials who tell him he is under arrest and sentenced to death. The ensuing nightmare is less a fear of the present than a frantic clawing toward some obscure answer lurking in the past. Why me? What have I done? Memory, which often offers explanatory feedback to real-time experience, sits back out of view, silently watching, perhaps not even there at all. Dae-su’s captor, Lee Woo-jin, embodies this temporal voyeurism as he silently surveils, dropping breadcrumbs whilst disappearing from view. Dae-su becomes Woo-jin’s plaything, as the latter coaxes half-formed memories from our protagonist.

Maybe, then, memory does not draw us away from our present. Instead, maybe it is urgent, contemporary, and current. Park Chan-wook’s stylistic direction emphasises this, as images from the present bleed into the past, and seemingly linear sub-plots suddenly veer backwards, forming self-contained episodes. Visual motifs recur like poetic refrains, constantly threading the past back into frame, as though only one temporal frame exists: the now. Watching as the film develops its own memories, we become accustomed to thinking of them as native to the present, rather than as a long-lost past. Chan-wook trains us into thinking in, and through, memories. Desperately looking back, then, is not the answer for Dae-su; his memory is a thought process native to the present, both shaping it and being shaped by it.

Like Proust and his madeleine, much of Dae-su’s past is condensed into sensory phenomenology. This is most evident when he seeks out the dumpling restaurant that fed him during his imprisonment. Unlike Proust’s involuntary experience of sudden recollection, Dae-su devours dumpling after dumpling, eating his way into his past. Dae-su’s first meal after his release is a live squid – “I want something alive” he demands of the sushi chef, an order that recalls his persistent threat to devour the flesh of his captor. As Roger Ebert pointed out, Dae-su wants the squid’s life, not its meat, and this enunciates his critical mistake. Voraciously looking into his past and seeking to restore the life he has lost, Dae-su neglects what is right before his eyes. The sushi chef, Mi-do, whom he will soon fall in love with, is his daughter.

The Ancient Greeks believed that one stands with one’s back turned to the future, facing the past. We do not look towards the future, because how can we? It is oblique and unknowable. Dae-su stands thus, and unwittingly falls in love with his own daughter. Chan-wook twists the past and present into a knot, tying Dae-su into a contorted, tortured position. Dae-su’s sexual mesalliance is ultimately explained to him, and he becomes a wretched creature, cutting his own tongue from his mouth. Better not to talk at all than to talk with the loose tongue that incited this chaos, in the mouth that kissed his own daughter’s. The strength and hardness he achieved through his imprisonment is gone. He is now a blood-soaked, incestuous dog, crawling on all fours. The pull of the past and present has rent and ravaged him. Dae-su’s tragedy is his inability to see memory as indistinguishable from his present. His life is partitioned by his imprisonment, constituted by a “before”, (which he can no longer relate to), and an “after” (which is consumed by his vengeful anger). This temporal partition blindsides him. Even though Woo-jin sneeringly reminds Dae-su to ask not why he was imprisoned, but why he was released, implying that his past infractions somehow exist before his eyes in the present, Dae-su cannot oblige: his back his turned. Woo-jin’s plan mobilises this; he anticipates Dae-su’s blind rage, because he shares it. “How’s life in a bigger prison?” he asks Dae-su over the phone, soon after his release. The question seems directly mocking, but bears a hidden irony: Woo-jin is similarly incarcerated in that bigger prison, living in a temporal deadlock with his past. By engineering Dae-su’s incest he reveals his own sexual liaison many years earlier with his sister Lee Soo-ah, destroying himself too, as the two men revisit this sin.

Memory is gestation. It develops and changes. Sad memories can become happy. Happy memories can become sad. For Soo-ah, this is literalised by her phantom pregnancy. Filled with retrospective guilt at the consensual affair she had with her brother, her belly grows and brings forth evidence of their illicit relationship. Evidently, memory is not a place we retreat to by choice, or a static museum of experience: it is an active, flexing, organic presence that imposes itself on us constantly. Soo-ah’s guilty memory brings about her death, and Woo-jin’s obsession with punishing Dae-su for spreading rumours of the incestuous affair dictates his cruel life henceforth. Woo-jin does not move on or eradicate his memory, nor does he purge Dae-su of the memory of witnessing the sibling’s sexual affair; all he does is transfer these intense feelings into the next chapter of his life, where they equally dominate and destroy. That’s life in a bigger prison.

We are left feeling sorry for Mi-do, Dae-su’s poor daughter. She does nothing wrong but suffers immensely. Perhaps she is the emblem of memory’s illusory distance: an idealised past that doesn’t exist anymore, that is in fact rooted in the disappointing terrain of present reality. This is how memory works. It lies to us that our lives are split between the now and the then. But it is all now. When we think we are escaping the present, we are just extending it in a different direction. Oldboy takes a page out of Samuel Beckett’s book in that way, constructing life around a temporality outside of the one you inhabit, which only seems to fracture and pollute the present, turning it into an absurd, purgatorial nightmare. Beckett’s purgatory is linguistic, Chan-wook’s is physical. The former thickens language into a senseless mass where characters aimlessly wait for things to happen, whilst the latter does so anatomically, as bodies violently collide, atomise, and breach sexual taboos. Escaping the present through memory enables this destruction of its order and stability.

It is all present. That is the journey, and the meaning of it all, and, perhaps, the meaninglessness of it all. As Dae-su says himself, in true Beckettian fashion: “You need not worry about the future. Imagine nothing”. The same can be said of the past in Oldboy. Facing the past for too long means submitting to this nothing-ness; Dae-su does so, and we find him vacantly staring into a snowy wilderness, unable to speak at the end of the film. The emptiness of his past has dictated the emptiness of his present. He no longer imagines nothing, he lives it.

by Ethan Radus