In their short film Fuori Programma, PhD student Irene Ros looks at the collective memory of Italian right-wing political violence (1969-1980) through interviews with Italian women who were young adults at the time.

Fuori Programma [Unscheduled or Off Plan] is a short experimental documentary film, that edits together the memories of the first nine participants of the SGSAH-funded PhD project ‘Performing Stragismo and Counter-spectacularisation: Italian right-wing Terrorism and Its Legacies’. The project investigates the divided collective memory of the Italian right-wing terrorist attacks (1969-1980), through the under-represented narratives of Italian women who were young adults in the Seventies, and who belonged to the majority of the population, (i.e., people who were not involved in political violence).

Academic research on Italian terrorism usually engages with the main actors of these events, namely: the victims, their families, and the former terrorists. Furthermore, the media’s discourse about terrorism calls women into question only to play the role of victims (grieving mothers, wives, daughters), or sexually deviated former terrorists. My project intends to offer an alternative to the predominantly male-centred discourse.

My practice draws from Dwight Conquergood (2002), who defines the practice as “participatory epistemology” or “engaged knowledge” and builds on Phelan’s (1996) distinction between marked and unmarked.

“As Lacanian and Derridean deconstruction have demonstrated, the epistemological, psychic, and political binaries of Western metaphysics create distinctions and evaluations across two terms. One term of the binary is marked with value, the other is unmarked. The male is marked with value; the female is unmarked, lacking measured value and meaning”. (Phelan 1996, 5)

I argue that, as a result of the binary division that characterises Western knowledge, oral history is a domain that pertains to the feminine, in contrast to the written page. My project employs oral history as a methodology; the conversations were designed as semi-structured interviews, and this flexibility allowed me to take into consideration the participants’ need to feel listened to and to connect (the conversations with the participants started in February 2021, when Italy was going through a Covid-19 lockdown), and at the same time to develop a methodology that aimed at the co-creation of knowledge. The semi-structured interviews proved to be the right choice when, during the conversations, I realised how the collective memory of the right-wing attacks was not only divided but lacking and often erased. Through this method, I could collect broader points of view about the 1970s and question what memories ‘over-wrote’ those of the right-wing bombing attacks.

Each participant sat through three one-hour meetings: the first focused on their background, revealing the relationship of their family of origin to the legacy of the Second World War, as well as their childhood, youth and adulthood. The second unravelled from an object that they were invited to bring in, as a memento of their lives in the 1970s. From the object and the memories connected to it, I encouraged them to identify some starting points (characters and events) to narrate life in Italy in the 1970s. Each participant unfolded the narration differently, some entangled their personal stories with historical events, whereas others outlined a more conventional narration of the historical facts or merely described those years only through personal memories.

In the third conversation, the daughters or sons were invited to join, and I addressed some of the same questions I asked the women to their children (Did you talk about politics in your family? Were people profiled according to their political beliefs?), exploring the recurrent patterns linking how politics was discussed in their family to the way in which they talked about it to their children.

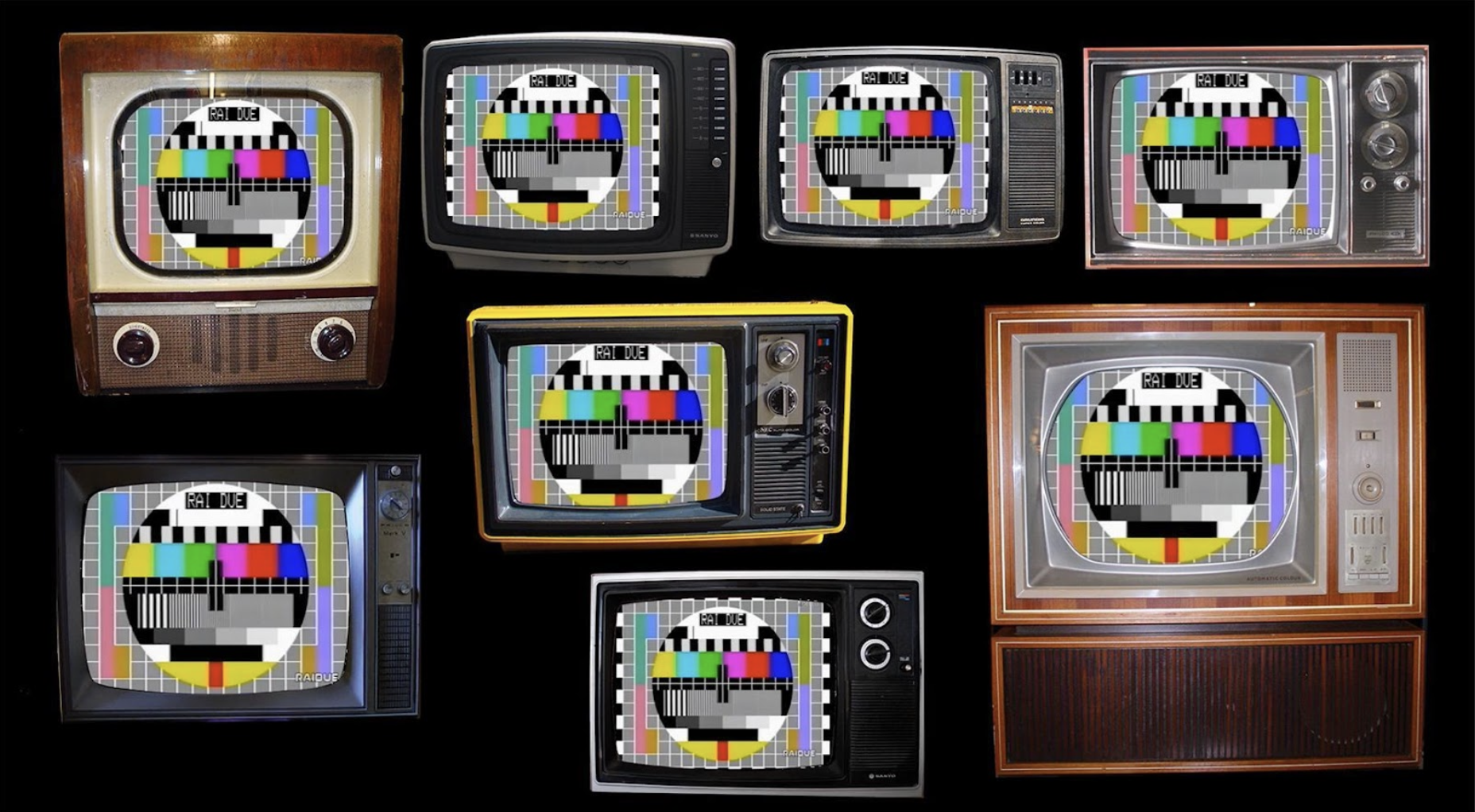

The shape and content of the film were informed by the participants: the aesthetics sprang out from the first conversation I had with the first participant (Figure 01) and accompanied me throughout the creation. While talking about her childhood, the participant mentioned the social impact of owning a tv at the end of the 1950s, explaining how her family home’s garden became a sort of community centre when some tv programmes were broadcasted.

“I remember that we had, at one point… we were the only ones with a television – you know there were those famous tv shows – so they came in the summer… we put the tv near the window and the courtyard – it looks like a movie but it was like this – it was full: about fifteen, twenty people with their chairs to watch the tv with us.”

Participant A, 25 February 2021

Figure 1: frame from the film Fuori Programma

Initially the centre of social gatherings, televisions became the main source of any memory about the right-wing bombing attacks, and as a result I decided to visually highlight their relevance, yet at the same time create a sense of subversion. Moving the participants to the foreground (each framed by an old television) and everything else to the background (footage showing the aftermath of the attacks), the aesthetics challenge the concept of ‘political subject’ and represent (or, better, create a space to self-represent) the participants as such. Through the televisions’ “vintage vibe”, the low quality of the videos finds its reason for being. The dialogue emerged from comparing the transcriptions: the sentences I found more interesting, or that resonated with those of other participants, were copied into a document, with a different colour assigned to each participant, to give equal representation to everyone (Figure 2).

Figure 2: dialogue from the participants

Editing all of the memories together, I could, on the one hand, begin to theorise a difference between spectacular and memorable. On the other hand, I could identify a pattern amongst the memories that overwrote those of the right-wing terrorist attacks. Although the participants’ fathers were the ones experiencing the spectacularity of the Second World War (as fascist soldiers or as partisans), they often did not talk much about their experience. Instead, the mothers and the women in the family were the ones talking about the everyday life during the war. Similarly, the spectacularity of right-wing terrorism was carried through the images of the news, but often the participants could not find connections between these spectacular images and their personal stories, whereas their embodied memories of every day were the ones they wanted to talk about.

During the Seventies, women were not only threatened by the right-wing attacks as citizens, but also (more or less consciously) by the fascist ideology as women. This second threat felt more urgent and pressing, involving the women’s bodies directly, and was not only expressed by violent episodes (such as the bombing attacks, but also group rapes like the infamous one perpetrated against theatre maker Franca Rame), but by a creeping culture that was not ostracised and antagonised by Italy’s unofficial state religion, Catholicism, which on gender-related issues was on the same side as the right-wing militants, against divorce and abortion. If, as Foucault (1989) theorises, history is the unravelling of forces driven by individual bodies, it seems fair enough that the participants over-wrote the memories of the right-wing political violence with those that embodied their response to this violence, and performed new ways to be women, where gender performativity is understood as “a repetition and a ritual, which achieves its effects through its naturalization in the context of a body” (Butler 2006, 203).

In the film, these overwritten memories were edited to remark on the conscious and unconscious connections with the main topic of my research. Although this is more evident in the second outcome of my research (figure 04) (an installation including five tablets from which some of the newer participants answered some questions, giving the audience an interview-like experience), in Fuori Programma, the process of creation is exposed. The dialogue results from assembling different conversations, laying bare in front of the audience the incompleteness and partiality of the material which they can ultimately see. Furthermore, the cuts reveal the power structure, and encourage a reflection on agency in participatory practices.

Even though the participants were subject to what Loughran, Mahoney and Payling describe as the “online disinhibition effect” (Oral History, Spring 2022, Vol.50), they were aware of being recorded, and hence were, to different degrees, performing themselves. However, I shaped their visibility as political subjects, based on what I determined to be representable, but also relatable.

Figure 3: frame from the interactive installation Siamo in Linea

The participants’ virtual presence gives the audience the sensation of authenticity and truth-telling, similar to what happens in many testimonial theatre plays, in which the presence of the witnesses is at the centre of the work. In her Performing the Testimonial: Rethinking Verbatim Dramaturgies, Amanda Stuart Fisher asserts:

The discourses of authenticity associated with verbatim theatre tend to circulate around two interconnecting ‘promises’ that disclose different kinds of truth claims. (Stuart Fisher 2020, 81)

The two promises are first to show the audience a source of truth and, second, the sincerity of the personal narratives. These claims do not consider the possibility of faulty and altered (i.e. performed) memories, which could be mitigated if they are put in conversation with original documents, a strategy I only partially employed in the Fuori Programma. Recognising the memories’ limitations, and still wishing to work with under-represented subjects, I have often been questioning: what constitutes a legitimate historical truth?

During the SGSSS-SGSAH-funded Symposium Doing Feminist Research (4-6 May 2022, Edinburgh), Rashné Limki suggested, “It is better to do good work than legitimate work”. Without disavowing the existence of historical truth, I hope his project will allow me to do some good work. I am currently employing the participants’ memories in creating a live performance; this will enable me to include controversial memories not included in Fuori Programma, giving them context. Since the participants’ stronger memories originated from a physical engagement with the senses, I wish to offer the audience the gift of presence and to re-present memories through the ephemerality of the performance. Fuori Programma has been presented so far during a Being Human café at the Scottish Oral History Society in Glasgow (November 2021, as well as at the Connect-Fest at the Centre for Contemporary Art in Glasgow (June 2022), and at the Davamot Symposium in Sweden (December 2022).

Fuori Programma, the live performance, will take place on Tuesday, 28 March, at 7 pm, at The Pleasance Theatre, Edinburgh.

Link for the seats: https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/e/fuori-programma-tickets-539031637137

To watch Fuori Programma, click on this link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_ZZmgHGhvik&embeds_euri=https%3A%2F%2Fireneros.net%2F&feature=emb_imp_woyt”

References:

Amanda Fisher Stuart. 2020. Performing the Testimonial: Rethinking Verbatim Dramaturgies. Manchester: Manchester University Press

Dwight Conquergood. 2002. Performance Studies. Interventions and Radical Research. The Drama Review, Vol. 46, No. 2 (Summer, 2002), pp. 145-156

Guy Debord. 1990. Comments on the Society of the Spectacle. London and New York: Verso

Guy Debord. 2014 [1967]. The Society of the Spectacle. Berkeley: Bureau of Public Secrets

John Foot. 2009. Italy’s Divided Memory. New York: Palgrave Macmillan

Judith Butler. 2006. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. Routledge

Judith Butler. 2011. Bodies that matter. Routledge (PDF)

Michel Foucault. 1989 [1966]. Order of Things. London and New York: Routledge

Michel Foucault. 2000. Power. New York: New Press.

Peggy Phelan. 1996. Unmarked: The Politics of Performance. London, New York: Routledge

Ruth Glynn. 2013. Women, Terrorism, and Trauma in Italian Culture. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan

Tracey Loughran, Kate Mahoney, Daisy Payling. 2022. Reflections on remote interviewing in a pandemic: negotiating participant and researcher emotions. Oral History, Spring 2022, Vol.50

by Irene Ros

University of Edinburgh

University of Strathclyde, Glasgow