The brain appears to integrate simultaneous information from all the senses from birth. (See our blog for Multisensory processing.) However, when the infant is fully sighted, vision most often takes the lead. So what happens when vision is impaired?

This time, I have invited Stefania Petri, Unit for Visually Impaired People (the UVIP Lab), the Italian Institute of Technology, to write about the integration of tactile and auditory cues in infants. Stefania is part of the MySpace project, which investigates how infants and children who are blind process audio-tactile information. The project is led by Dr Monica Gori, Head of the UVIP Lab, and Stefania contributes to the development of the early intervention system iReach.

For newborns, vision is not only about recognising faces and objects. Sight guides movement, play, and exploration. It allows infants to coordinate their actions, interact with caregivers, and gradually make sense of the world. When vision is missing or severely impaired, these basic experiences are disrupted from the very beginning of life. Indeed, infants with visual impairments often face delays in motor development, difficulties in social interaction, and challenges in learning how to explore space.

Why Touch and Sound Matter

Vision usually guides the other senses, helping infants build a coherent sense of space. For a sighted child, seeing a toy, hearing its sound, and touching it all come together to form a single, integrated experience. To construct this spatial map, infants who are blind must rely on other senses, such as touch and hearing.

Both senses are present from birth, and both provide spatial cues: touch gives direct, body-centered information, while hearing allows orientation toward events and objects at a distance. Understanding how these two senses work together in the absence of vision is crucial for developing strategies that support the growth of children who are blind.

Studying multisensory spatial perception

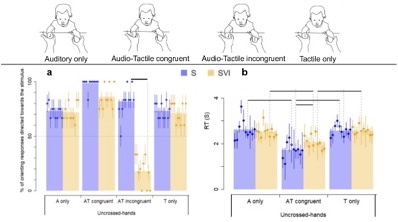

To explore this, we used a well-established paradigm – presenting auditory and tactile stimulations on the hands of the infants. We used a non-invasive device and collected behavioural data. The stimulation could be presented in a congruent way, with touch and sound on the same side of the body. Or, in an incongruent way, for example, touch on the right and sound on the left-hand side. By comparing the responses from infants who were blind and infants who were sighted, it became possible to explore how the two groups oriented and how quickly they reacted under different conditions.

This method may seem simple, but it addresses a fundamental question: when vision is absent, how do infants resolve conflicts between touch and sound? And do they still benefit when both cues point in the same direction?

What We Found

The results revealed clear differences between the two groups:

- When touch and sound are in conflict — for example, when a vibration is felt on one hand, but the sound comes from the opposite side — infants who are blind are less likely than their sighted peers to orient toward the sound. This suggests that they rely more strongly on tactile cues when making spatial decisions.

- When touch and sound are congruent, infants who are blind show evidence of multisensory integration. Specifically, their reaction times are faster when both cues are presented together compared to when they are presented separately. While sighted infants tend to integrate such cues more efficiently, infants who are blind nevertheless reveal that they can combine information across senses in a beneficial way.

(Top) Four experimental conditions: auditory stimulation alone, congruent audio-tactile stimulation, incongruent audio-tactile stimulation, and tactile stimulation alone. (Bottom) Results: (a) percentage of orienting responses directed toward the auditory stimulus and (b) reaction times to the stimulus. Blue bars represent sighted infants (S), and yellow bars infants who were severely visually impaired. Bold black lines indicate statistically significant differences between conditions.

(Top) Four experimental conditions: auditory stimulation alone, congruent audio-tactile stimulation, incongruent audio-tactile stimulation, and tactile stimulation alone. (Bottom) Results: (a) percentage of orienting responses directed toward the auditory stimulus and (b) reaction times to the stimulus. Blue bars represent sighted infants (S), and yellow bars infants who were severely visually impaired. Bold black lines indicate statistically significant differences between conditions.

Published with permission. Gori, M., Campus, C., Signorini, S., Rivara, E., & Bremner, A. J. (2021). Multisensory spatial perception in visually impaired infants. Current Biology, 31(22), 5093-5101.e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2021.09.011

These findings highlight an important message: even without vision, multisensory stimulation, particularly the integration of sound and touch—can enhance performance and support the gradual development of spatial and motor skills.

Practical Implications

These insights are not just theoretical. They guide the development of both habilitation and rehabilitation strategies and supportive technologies. For instance, play-based training sessions that combine vibration with sound in congruent way could strengthen early sensorimotor skills and might help infants who are blind practice reaching and moving toward objects.

One practical example inspired by this research is iReach. iReach is a small, wearable system made of two units, or tags that communicate via wireless. By attaching an anchor tag to a bracelet on the child’s wrist and another tag to a toy, the device allows infants to sense changes in vibration and sound as they approach the object: As the child moves closer to the toy, the bracelet changes its vibration and sound, giving intuitive feedback about distance.

An early prototype has been tested in a safe, playful setting with sighted children who were blindfolded. In one of the activities, the children had to place objects into a box positioned farther away, which contained the spatial reference tag.

a) iReach units: Tag (left); Anchor (right). b) Example of Tag positions: Anchor on infant’s body midline (left); external object (right). c) Example of use of iReach: The sound emitter and waveform icons represent the auditory and tactile stimuli, respectively. An increase in icons size indicates a corresponding increase in feedback intensity and frequency.

a) iReach units: Tag (left); Anchor (right). b) Example of Tag positions: Anchor on infant’s body midline (left); external object (right). c) Example of use of iReach: The sound emitter and waveform icons represent the auditory and tactile stimuli, respectively. An increase in icons size indicates a corresponding increase in feedback intensity and frequency.

Published with permission: Gori, M., Petri, S., Riberto, M., & Setti, W. (2025). iReach: New multisensory technology for early intervention in infants with visual impairments. Frontiers in Psychology, 16(May) https://do.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1607528

When wearing the iReach bracelet, the children completed the task both faster and with more accurate movements. These early observations suggest that iReach can make exploration more intuitive and engaging for children who are blind.

Importantly, iReach is not a sensory substitution device, which often overload users with complex signals, it uses a child-friendly “language” of touch and sound to encourage active movement and exploration.

Conclusion

Infants who are blind grow up in a world where touch and hearing are the main senses that support their exploration of the world. Our studies show that they rely more on touch than on sound when the senses are in conflict, but they also benefit from integrating the two when the information is aligned. Recognizing how touch and sound work together, we can take important steps toward creating early interventions that respect children’s natural abilities and provide them with the best possible start in life.

See our blog for Activities; especially 79-81.

Some suggestions for further listening and watching:

Baby’s Fine and Gross Motor Skills

Get “Inside the Mind of a Baby”

Multisensory spatial perception in visually impaired infants

The Tactile System & Body Awareness In The First 3 Months

Vision Development: Newborn to 12 Months