Sometimes the brain gets confused by visual information, in the same way as with sensory illusions and magic tricks (see our blog for Sensory illusions before and after vision and Magic without vision).

In this post, life-long magician “The Fantastic Kent Cummins!” reflects on how his brain is sometimes tricked when he has lost more vision. And on how this is similar to when it is fooled by sensory illusions and magic tricks. Kent Cummins has been a magician for more than 75 years. Amongst other things, using the fascination and fun of magic to teach children about their eyes. And winning the international Auditory Challenge in 2024. About 25 years ago, Kent was diagnosed with Age-related Macular Degeneration (AMD). AMD affects people’s central vision. For example, making it difficult for them to recognise faces and read regular print. Loss of eyesight is gradual: the first symptom is often blurred or distorted vision. AMD rarely leads to blindness.

“The hand is quicker than the eye. That’s why there are so many black eyes!”

It’s a very old joke…and it isn’t even based on fact. The hand is not actually quicker than the eye … unless, like me, you are visually impaired.

Losing one’s sight is not a laughing matter.

It must be magic!

I have been a magician for more than 75 years. (I performed my first magic trick in 1949, at age six.)

As a young man, I had better than 20-20 vision, which probably helped me learn and perform sleight of hand and other magic tricks and illusions. At age 60, I was diagnosed with AMD (Age-Related Macular Degeneration). For many years, it was just a diagnosis … I had not lost enough vision to even notice it.

But in my seventies, I started noticing the decreasing vision more and more. I needed stronger reading glasses, and better magnifiers. Fortunately, I am retired from the US Army as a Lieutenant Colonel, and the Veterans Administration (VA) provides all of my vision care.

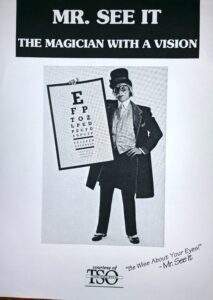

The Magician with a Vision

When I became a full-time professional magician in 1986, I was hired by Texas State Optical (TSO) to be the third of three magicians who taught kids about their eyes through performing specially-themed magic shows. Our character was called, “Mr. See It, the Magician with a Vision,” and we also each had a small rabbit named, “Iris the Eye Bunny.”

During the next three years, Iris and I did more than 500 shows throughout four states. (Texas State Optical also had stores in Arkansas, Louisiana, and Oklahoma.) I wrote a song called “The Eyeball Rap” which taught kids about the parts of the eye, and I was well-paid … until TSO was bought out by an international conglomerate, and all of these programs were cancelled.

Ironically, nearly forty years later, I have become “The Magician with LOW Vision.”

I wear a button that says, “I Have Low Vision.” But for several years, I did not wear it on my magician costume, because as a magician, I should be all-powerful. Then last year I realized that even Superman had his Kryptonite. When I started wearing the button during my magic shows, and doing an Eye Chart trick while explaining why I wore the button, I discovered that kids related to me better … even sharing their own stories of needing to wear glasses.

Seeing is believing

Magic is typically a visual performing art. Although magicians will use all of the senses to entertain (and fool) their audiences, magic tricks are usually understood by the spectator’s vision. That’s why they came up with the expression, “The hand is quicker than the eye.”

But as I already noted, saying that is just another way to fool someone. The real secret is more likely to involve misdirection than quickness of the hand.

Auditory Illusions

A popular auditory illusion is that created by a ventriloquist, when they make it appear that sounds are coming from somewhere other than their vocal cords. When watching a skilled ventriloquist, we forget that the “dummy” is not real. It’s called suspension of disbelief, and it explains why we also cry at sad movies…even when we know that it is just a made-up story.

But ventriloquists do typically rely on the audience being able to see the prop being manipulated. A ventriloquist named Ian Varella was fond of blowing up a balloon and squeezing the neck of the balloon as the air went out, making a distinctive squealing sound. But the audience laughed when the sound continued even after there was no air left in the balloon! That’s right, Ian was making the sound with his mouth…not the balloon. (Ian was also an accomplished magician.)

The Magic of AMD

I see things which are not there…and sometimes don’t see things that are definitely there.

The first time I noticed this was more than ten years ago, when I was getting ready to exit my driveway onto the road ahead. I looked both right and left, confirming that I saw no cars in either direction. But just as I started to enter the road, a car came zooming by from my right, honking its horn and no doubt cursing at me.

Why didn’t I see the car? Because at first it happened to be in my blind spot, the portion of my macula which no longer provides information to my brain. So, the brain just filled in more empty road!

The next episode happened when I walked out of my front door to check the mail in the mailbox on the front curb. But the mailbox was gone. I was not too surprised, since boisterous teens sometimes had fun by driving down the street and hitting mailboxes with a baseball bat. But I was surprised when I blinked my eyes and the mailbox reappeared…just like magic!

No, I do not drive any more. You’re welcome.

A less dangerous but perhaps humorous thing happened when I needed to use a public restroom. I clearly saw the sign, which said, “MEN.” But as I started to enter, I noticed women exiting. That’s right, the “WO…” had been in my blind spot!

It has been fascinating, learning how my brain can fool a life-long magician!

See our blog for Activities; especially 73-75.

Some suggestions for further listening, reading, and watching:

The Magician’s Code – Kent Cummins