Certain information is associated across the senses. Some of these crossmodal associations are shared by most people. For example, in the Bouba/Kiki-effect, more than 95% of people around the world match the spoken word “Bouba” with a rounded shape and the spoken word “Kiki” with an angular shape. Other crossmodal associations are subjective; while some people see colours when hearing music, others read braille in colour. And it seems these subjective associations between the external senses may be closely related to the internal senses. (See our blog for How anxious individuals perceive odours, Emotional perceptions associated with sound environments, and Growing into one’s own body.)

I have invited Dr Marina Iosifian, School of Divinity, University of St. Andrews to write this post about crossmodal associations between visual paintings and sounds. Dr Iosifian has contributed to several scientific papers and public outreach events on how the internal senses might create crossmodal associations between vision and hearing.

Have you ever noticed that certain colours seem to “fit” certain sounds? For example, dark red might feel like it matches a low, deep voice, while pink feels more like a high, light voice. These kinds of connections between different senses—such as sight and hearing—are called cross-modal associations. Researchers study them to understand how our brain brings together information from different senses to form a unified picture of the world, even though each sense works separately (our eyes only see, our ears only hear).

Why do these associations happen? One possible explanation involves emotion. For instance, dark red and a low voice might both feel connected to sadness, while pink and a high voice might both be linked to happiness or playfulness.

But emotions aren’t the only reason. Another explanation has to do with the body’s movements and sensations. For example, when people are asked to name two round tables—one large and one small—they often call the large one “mal” and the small one “mil.” This may be because of how our mouths move when saying these sounds: “mal” requires a wider, more open mouth shape, similar to something large, while “mil” involves smaller, tighter movements, like something small.

In our study, we explored these bodily mechanisms—the ways our physical sensations and actions might shape how we connect sights and sounds—to better understand how cross-modal associations arise.

To explore these associations, we collected a set of sounds produced by the human body, such as the sound of someone drinking. We called these embodied sounds. To provide a contrast, we also included sounds that cannot be produced by the human body, such as electronic or synthesized sounds, which we called synthetic sounds.

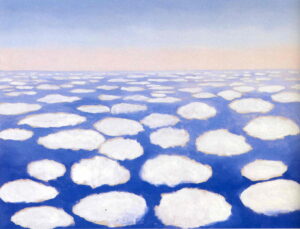

Because we were interested in how sounds are connected with visual experiences, we also gathered a collection of images. These included two types of paintings: figurative paintings, which show recognizable subjects like people or objects (eg, The Garden Walk by Emile Friant), and abstract paintings, which do not represent specific things (eg, Sky above clouds by Georgia O’Keefe). We then paired the paintings with the sounds and asked our participants a simple question: “Does this sound and this painting fit together?”

We found that embodied sounds were more often associated with figurative paintings, while synthetic sounds were more often linked with abstract paintings. This suggests that the body—and the way we experience sensations physically—plays an important role in how people connect what they see with what they hear.

Why might these associations occur? One possible explanation lies in the difference between concrete and abstract ways of thinking. Figurative paintings depict familiar, tangible things—people, objects, and scenes—so they may evoke more concrete thinking. Abstract paintings, on the other hand, invite a more imaginative or distant mindset.

Interestingly, previous research has shown that people tend to associate abstract art with more distant situations—whether in time or space—compared to figurative art. This idea is related to the psychological concept of psychological distance, where concrete things feel close to us and abstract things feel farther away. Our results suggest that this distinction between the concrete and the abstract may also shape how we connect sights and sounds.

Some researchers believe that psychological distance is one of the main concepts which can help us understand how the mind works. They developed the Construal Level Theory or CLT – which explains how our mental distance from things – called psychological distance – affect the way we think about them. Psychological distance can take many forms: something can feel distant in time (happening in the future or past), in space (far away), in social distance (involving people unlike us), or in hypotheticality (something uncertain or imaginary). It is suggested that people think about things that feel close to them—such as events happening soon or nearby—in a more concrete and detailed way. In contrast, things that feel distant in time or space, are understood in a more abstract and general way.

If abstract thinking is linked to distant, less embodied experiences, and concrete thinking to close, bodily ones, then the way we perceive and connect sounds and images may depend on how “distant” or “close” they feel to us psychologically. In other words, our sense of distance—both mental and sensory—may shape how we integrate what we see and hear.

Thus, the concept of abstraction offers valuable insight into how people interpret and understand the world around them. Art, in particular, provides a powerful way to explore these processes. Recent research suggests that engaging with beauty in art can encourage people to think in more abstract ways, making art an especially meaningful tool for studying perception and the connections between our senses.

See our blog for Activities; especially 85-87.

Some suggestions for further reading, listening, and watching:

Applying Bodily Sensation Maps to Art-Elicited Emotions

How Does Your Body React to Art?

Processing Internal Sensory Messages

See What Your Brain Does When You Look at Art