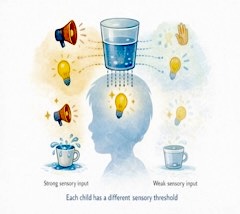

Although all brains perceive and process sensory information, people differ in how much sensory input it takes for their brain to respond. For example, some only notice vivid colours, while others are overwhelmed by soft pastels – without trying to actively change the colour by adding or removing light. These groups simply respond passively. Other people seek sensory input, sometimes even creating it themselves by fidgeting, and some become overstimulated by certain types of input and withdraw. Both of these groups respond actively. (See our blog for the crossmodal correspondences between the senses, Crossmodal brain plasticity and empowering of sensory abilities, Multisensory processing, Growing into one’s own body and How the internal senses may connect sight and sound). And, how the brain responds to sensory information, may also affect how well people sleep.

In this post, I have invited Assistant Professor, Büşra Kaplan Kılıç, University of Health Sciences, Turkey to write about how people’s responses to sensory information can affect their sleep. She calls it: “the hidden link between sleep and sensory processing.” Her research includes several scientific publications on sensory integration, sensory processing, and sleep.

The Hidden Link Between Sleep and Sensory Processing in Toddlers

When a baby or toddler has trouble falling asleep, it is often thought to be due to fussiness, habit, or excessive activity. However, science tells us that sleep is not only a state of rest, but also a process closely related to how the baby perceives the world. Especially in the first years of life, the connection between sleep and sensory development becomes quite important.

So, the question we should be asking is not, “Why aren’t they sleeping?”. But rather: Do children perceive the world the way we think they do?

How Do Children Perceive the World?

We constantly receive information from our surroundings: light, sound, touch, movement, taste, smell… Our brain filters and organizes this information and ensures we behave accordingly. This process is called sensory processing. Each individual has a different threshold value for these stimuli. Some of us can comfortably read a book in a crowded environment, while others may be disturbed by even the ticking of a clock.

Similarly, some young children notice environmental stimuli immediately and experience them very intensely. Others notice stimuli later or ignore them. Some become distressed and prefer to avoid them. All these differences are part of children’s sensory profiles and are not problems in themselves. However, when these sensory characteristics are combined with a sensitive process such as sleep, challenging situations may arise. This suggests that sleep is not only a behavioral problem, but also deeply connected to the child’s biological makeup and sensory world.

We therefore conducted a study1, with 220 children aged 1-3 years, half with and half without sleep problems, to explore two key questions:

- Do children with and without sleep problems have different sensory responses?

- In which areas do these differences appear?

The results were quite surprising

Compared to their peers, the sensory profiles of children in the group with sleep problems differed from typical development in three areas.

- They had excessive sensory sensitivity

Children with sleep problems can be much more sensitive to sounds, visual stimuli, or touch. These children become irritated more quickly by stimuli in their environment and react more intensely. This can cause them to wake up at the slightest sound during sleep. Even small movements during sleep, such as turning or stretching, can cause rapid arousal in some children and make it difficult to maintain sleep.

- Their sensory avoiding tendencies were high

Some children may feel sensorially overwhelmed because they notice stimuli very quickly. This situation can increase the child’s tendency to avoid daily activities, starting with bedtime routines. A constantly avoiding and alert profile can cause the child to become restless during bedtime routines. For example, brushing teeth, putting on pajamas, and the characteristics of sheets and blankets can be overly stimulating.

- They exhibited intense low awareness behaviour

Another notable finding in the study was the low registration behaviour exhibited in response to sensory stimuli. In other words, some children needed more intense input to notice stimuli from their environment. These children may struggle to notice the calming stimuli in their environment (such as lullabies or gentle rocking). In this case, they may miss the relaxation signals needed to fall into sleep. Consequently, the transition to sleep can naturally take longer.

This study tells us that we should approach infant and child sleep problems from the perspective that “sleeping is difficult for them” rather than “they don’t want to sleep.”

Understanding sleep through the lens of sensory processing offers everyone a more nuanced and compassionate framework for supporting children and their families.

Recommendations

- Consider sensory processing as part of sleep assessments. When observing a child with sleep difficulties, it may be valuable to reflect on their sensory profile. How does the child respond to sound, light, touch, or movement throughout the day? Sensory sensitivity, avoiding, or low registration patterns may help explain why falling asleep or staying asleep is challenging.

- Think developmentally, not diagnostically. Sensory differences are part of typical developmental variability. Rather than labeling sleep difficulties as “problematic behavior,” interns and professionals are encouraged to view them as signals of how the child interacts with their sensory environment.

- Reflect on the role of the environment. Sleep does not occur in isolation. Lighting, noise levels, textures, and routines can all interact with a child’s sensory thresholds. Understanding this interaction can support more individualized and supportive approaches in both educational and clinical settings.

- Value interdisciplinary perspectives. Our study1 underscores the importance of collaboration between disciplines such as occupational therapy, psychology, pediatrics, and education. Addressing sleep difficulties through a sensory lens often requires shared perspectives and integrated support strategies.

See our blog for Activities; especially 88-90.

Some suggestions for further listening and watching:

– How do Parents Assess Their Child’s Sensory Profile?

– Understanding your sensory code

______________

1Kaplan Kılıç, B., Kayıhan, H., & Çifci, A. (2024). Sensory processing in typically

developing toddlers with and without sleep problems. Infant Behavior and Development, 76, 101981.