The brain integrates information not only from the five external senses – hearing, smell, taste, touch, and vision – but also from the three internal senses: interoception, proprioception, and the vestibular sense. (See our blog for the crossmodal correspondences between the senses, Vision, haptic touch, and hearing, Multisensory processing, and Food for thought: taste, smell and flavour). Interoception perceives the body’s internal state. Like hunger, thirst, and muscle fatigue. Proprioception perceives the body’s position. And the vestibular sense perceives the body’s balance, movement, and spatial orientation. However, the brain’s models of “what the body is” and “what the body can do” – known as “body representation” – appears to develop at different rates.

I have invited Lara Coelho, Unit for Visually Impaired People (the UVIP Lab), the Italian Institute of Technology, to write this post about children and their body representations. Lara has conducted multiple studies on how accurately people with and without vision estimate the size of their own bodies, including their feet and hands, and even the length of their own arm reach. The UVIP Lab is led by Dr Monica Gori.

What is body representation?

Have you ever closed your eyes and tried to touch your nose, only to miss slightly? Or remember the shock of seeing yourself in a mirror after a big growth spurt as a child? These are classic examples that demonstrate body representation knowledge is not as straightforward as it seems. Our brains constantly build internal models of the body’s size, shape, and capabilities. These models are what allow us to move gracefully, reach accurately, and feel that our body belongs to us.

Scientists call this body representation, and it underpins nearly everything we do: picking up a cup of coffee, navigating a crowded area, or even imagining ourselves in another person’s position. If this representation becomes inaccurate, whether after rapid growth, injury, or neurological changes, our perception of space and action can become distorted.

For children, whose bodies are rapidly changing, keeping track of “where my body ends” and “what I can do with it” is a constant learning process. Yet, we still do not fully understand how these internal maps develop, or whether different kinds of body knowledge grow at different rates.

In our new study, we explored exactly this question. We discovered that children can simultaneously underestimate the size of their hands and overestimate how far they can reach. This is a fascinating mismatch that reveals just how complex growing into one’s own body really is. The finding adds to the evidence that multiple “body maps” coexist in the brain, serving different functions. In children, these maps are still under construction.

Two ways of knowing your body

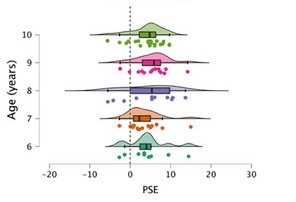

In our experiment, we asked 84 children aged 6 to 10 to complete two tasks. The first was a structural body representation task: children were blindfolded and asked to localize points on their own arm: the elbow, wrist, and fingertip, after being lightly touched by the researcher. This gave us a sense of how they internally mapped their arm’s proportions using touch and proprioception alone.

The second was a functional representation task. Here, children sat facing a table where small objects appeared at different distances. The children were no longer blindfolded.

Without moving, they had to decide whether they could reach each object if their arm was fully extended. This required them to judge their action capabilities; the “functional” length of their arm.

By comparing performance across tasks, we could see how these two types of body knowledge relate, or, as it turns out, how they diverge.

Children showed an intriguing pattern. When asked to locate their own body landmarks (the structural task), they consistently underestimated the length of their hand (the distance between the wrist and the fingertip). The forearm, however, was represented quite accurately. Put together, this meant the total arm was slightly underestimated.

In contrast, when asked how far they could reach (the functional task), children overestimated. They believed they could reach objects placed further away than their actual reach allowed. These two biases, underestimation of hand length and overestimation of reach, coexisted in the same children but were not correlated. In other words, children who thought their hands were short were not necessarily the ones who thought their reach was long.

This tells us that the brain maintains distinct internal models for “what the body is” and “what the body can do.”

Figures reprinted with permission: Cardinali, L., Coelho, L., Becchio, C., & Gori, M. (2025) Underestimation and Overestimation of Hand and Arm Length Coexist in Children. Developmental Science, 28(4):e70035, doi:10.1111/desc.70035

Why would the brain keep two different maps?

During childhood, the body changes rapidly, and sensory systems are still calibrating. The brain may separate these representations to allow flexible learning: one system keeps track of the body’s structure; another tracks its functional capabilities. They may update at different speeds as children grow and gain motor experience.

For example, the structural map (used to localize body parts) might depend more on proprioceptive and tactile cues, which can be noisy and slow to mature. The functional map, by contrast, is linked to action prediction and could be influenced by visual feedback and motor exploration, systems that reward overestimation, since trying to reach too far can promote learning.

Having two partially independent maps might therefore be an adaptive feature rather than a flaw. It allows children to explore the boundaries of what their bodies can do while still maintaining a stable sense of their physical form.

The bigger picture

This study builds on a broader effort to understand how the sense of body ownership develops. Our bodies are the lens through which we perceive and act upon the world. By studying how this lens changes during growth, we can better understand not only motor control but also self-awareness, perception, and even social cognition.

See our blog for Activities; especially 82-84.

Some suggestions for further listening and watching:

- Examples of information from the internal senses

- Interoception

- Proprioception

- Under- and overestimation of the size of hands

- Vestibular Sense