W11 Digital Curation

This week’s lecture provided insights into digital curation from the example of CCA Annex. Some of the ideas described by guest speaker Alex Misick were very interesting: the CCA Annex aims to be a platform that can collaborate with people, and is actively working to encourage audience interaction. For example, they initially used the broadcasting platform Twitch, but switched to Vimeo, which has more spokes features, to make it more interactive. The chat function allows for easy interaction as it has a place for a certain type of discourse. In terms of participation hurdles, the online event can be organised through a browser, so that people can literally just visit the site and watch the live event without having to post a separate link. Alex described this as the CCA Annexe literally being like an annexe, or a room within a room. He finds that this kind of idea prevents one-way transmission, which can be a problematic aspect of digital curation.

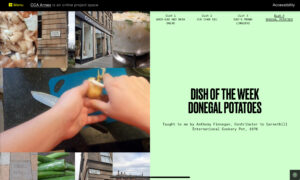

CCA Annex Home page (n.d.). Screenshot by the author. Available at https://cca-annex.net/

As an example of the work, he presented Sean Wai Keung’s Dish of The Week. This piece documents his attempts to recreate a recipe in his own kitchen, where the artist invited a community group in Glasgow to share their recipe with him. He presents the resulting footage alongside information about the communities he works with and the poems he was inspired by while cooking. As an example of the work, he presented Sean Wai Keung’s Dish of The Week. This piece documents his attempts to recreate a recipe in his own kitchen, where the artist invited a community group in Glasgow to share their recipe with him. He presents the resulting footage alongside information about the communities he works with and the poems he was inspired by while cooking. Alex drew on this work to explain that it was the result of thinking about the ways in which artists could work (and produce work) in digital online spaces during a time of pandemic. I regard the example of the potatoes as an experimental work that was building a local area within the idea of food and cooking, which is a history, like the stories and personal relationships of different people around food. Then, it’s essentially for the artists themselves, as it requires community conversation and a certain kind of learning.

Sean Wai Keung (n.d.). Dish of the Week. Screenshot by the author. Available at https://cca-annex.net/entry/dishes/

In addition, Alex argued that CCA annex acts as a digital extension of the material gallery. He stated that the programming and conversations for a physical exhibition are the same as for a physical one, but the context in which the work is completed is different from a digital one. Even though the Annex is a website, in a way, it has a relationship and visuality, both physical and building, with many of the projects and commissions they do. CCA’s projects are physical, they are in buildings, but they are not confined to them, they are like a transmission from the building. Additionally, the CCA works internationally. He explained that, in fact, 35% of visits to the CCA are international. The platform is for a variety of programming in the building, such as exhibitions, the Intermedia Gallery and the C Library, where commissions are obtained. Other benefits of digital curation, such as the ecological comfort of the programme and the flexibility of working with artists in terms of deadlines and timeframes, could be percieved from his conversation, although a potential problem also emerged. That is, online is difficult to maintain an audience – CCA Annex was an idea that was generated during the pandemic, but now that that situation is over, I realised that necessary to consider that purely online projects may not be in demand.

W10 Public Programmes

Reflection of the class

In this weekly session, I consider the discourse around curation and public programmes by examining a number of cases. Through various examples of public programmes, I examine questions of curatorial responsibility, strategy, related challenges, innovation and responsiveness.

To begin with, public programmes often act as broad-based educational practices within the curatorial framework of contemporary art, which Wilson & O’neill (2010) describes as an educational turn, a move towards the penetration of education as a device of social production and reproduction into broader cultural practices. This means that there is a movement whereby systems and programmes related to education are included within contemporary art and its associated critical framework.

Curation is moving from the development and evolution of exhibitions to functioning as a pluralistic discourse, extending contemporary art practice into local and everyday aspects of people’s lives. The provision of arts experiences for children and young people outside of schooling cannot compensate for the pressures and impoverishment of arts education in schools, but over the past two decades there has been an expansion of practices and ideas about learning in galleries (Pringle 2011). Evidence of an educational turn in arts practice can be found in the participatory educational programme ‘World Without Walls’ at the Serpentine Gallery in London. The programme professes to implement art practices for social action and change and actively engages with the public (Franks, 2020). His research argues that the project is community-based in Serpentine and centred on education and learning to bring about social and political change through participation in artistic practice. As a contemporary art institution, it is creating social change by creating opportunities to raise and discuss community issues to a shared local audience. Moreover, it provides an opportunity to use the educational process and for citizens to independently and proactively acquire certain knowledge through their observations and practices.

Another example is the New Bridge project, a case study assigned in-class: the NewBridge project is a public programme that responds to the diverse needs and interests of the community and adopts a participatory approach (The New Bridge Project, n.d.). Examples include community art projects and workshops, public discussions and panels, public art installations, community events and festivals. These programmes involve local artists and creators, deepen links with the local community and contribute to promoting sustainable social change and strengthening local identity. Both examples show that by creating opportunities to raise and discuss community issues to local people in the context of contemporary art, they are creating social change. Moreover, they use the process of education to provide opportunities for citizens to independently and proactively acquire certain knowledge through their observations and practices.

The New Bridge Project (n.d.). Available at https://thenewbridgeproject.com/about/about-us/

My Curatorial Project

Having described this public project as a broad-based artistic practice that encourages people to address common problems, I would like to discuss how this can work within my project, using the educational programme using street art as an example in W8. Within my curatorial project, I will be conducting a ‘Trail Walk’, which will explore and discuss street art with the public while walking through the streets of Bristol. During the course of the walking tour, the public will hear about the artists behind the murals and how the finished works came to be. Tour guides, including artists, will talk about each artwork on the tour, how they were created and the stories that inspired them. I think it is a participatory programme that is in line with the educational practices of contemporary art discussed in this week’s lecture, as the themes of street art, including local history, current politics and many social issues contained in the works, are opportunities for participants to develop proactive discussions on community issues.

References:

Franks, A. (2020). Expanding the gallery: Curation, pedagogy and social action in community-based arts programmes. In Debates in Art and Design Education (pp. 196-210). Routledge.

Pringle, E. (2011). The gallery as a site for creative learning 1. In The Routledge international handbook of creative learning (pp. 234-243). Routledge.

The New Bridge Project. (n.d.). The Late Shows 2024. Available at https://thelateshows.org.uk/2023/the-newbridge-project-1 (Accessed on April 8, 2024 )

Wilson, M., & O’neill, P. (2010). Curatorial counter-rhetorics and the educational turn. Journal of Visual Art Practice, 9(2), 177-193.

Peer Review From Ruochen Fang

In the framework, each post is clearly titled, maintaining coherence and aligning with course content, showcasing systematic progression of the project and reflection on curating. It covers lectures, seminars, site visits, readings, independent research, and personal project development, mirroring guidance from the toolkit.

Regarding design, your site has an attractive appearance. However, each post shows a lot and arranged in reverse order. Collapsing posts or arranging them sequentially could enhance readability.

In individual posts, you utilize subtitles for organization. Typically, there’s an initial reflection on learning content, followed by subjective insights on personal projects, which ensure clarity and readability. Your thorough referencing, with no omissions, reflects academic rigor. However, more additional content beyond the course material would enhance the depth of your work.

Concerning personal projects, you’ve showcased your creativity and project development, tailoring them around weekly themes. In Week 6, you explored combining publications with street art. Additionally, independent theoretical research is evident, such as sites and street art in Week 8. Further exploration of The World Atlas of Street Art and Graffiti (MacDowall & Schacter, 2023) which presents street art as an archival redefinition of urban space may be beneficial. Moreover, you provide rich evidence of independent research in Week 5, which are highly valuable. Understanding practices of experienced curators is invaluable for project development.

When posting blogs, you often use text paired with images to support the content, such as some examples on Week 4, which develop and support your project well, enhancing the richness of the posts. However, more pictures, especially records of your site visits, observations, and collections of local street art in the UK, would enhance visual engagement. The other sense in which the curator is a selector is by picking out works of significance from the undifferentiated mass of artistic output our times are embarrassed with (Ventzislavov, 2014).

Yet, two aspects merit consideration. Firstly, regarding learning around weekly themes, integrating reflections on personal and group projects would be help. For instance, discussing how field trips about archives in Week 7 contribute to your projects would foster deeper understanding. Combining The Street Art World (Young, 2016) which discusses street art as a cultural archive is a good choice. While your learning outcomes and project progress are evident, more connecting thoughts and discussions might help us think deeply.

Secondly, there’s a dearth of reflection on group discussions and your role within them. Incorporating content about group exhibitions and planning meetings would elucidate their impact on project development and your involvement. For instance, exploring whether others’ advice inspired your project, identifying emerging elements during group discussions, and discussing challenges within a group project context would be highly beneficial.

It’s worthwhile to think further about how to use the Internet medium to present street art, as exemplified by the website design of You and I Don’t Live In The Same Planet (Taipei, 2020) and the gamification of the online exhibition. Internet as an ‘actor’, can partially install meaningful moments of order in the playing field of chaos, or shed a different light on curatorial processes (Egger & Ackermann, 2021).

Reference List:

Egger, B. . and Ackermann, J. (2021) “Meta-curating: online exhibitions questioning curatorial practices in the postdigital age”, International Journal for Digital Art History, (5), pp. 3.18–3.35. doi: 10.11588/dah.2020.5.72123.

MacDowall, L. and Schacter, R. (2023a) The World Atlas of Street Art and graffiti. London: Frances Lincoln.

Ventzislavov, R. (2014). Idle Arts: Reconsidering the Curator. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 72(1), 83–93. https://doi.org/10.1111/jaac.12058

Young, A. (2016a) Street art world. London, UK: Reaktion Books.

You and I Don’t Live In The Same Planet (2020) [Exhibition]. Taipei. November 21, 2020 – March 14, 2021. Available at: https://www.taipeibiennial.org/2020/en-US/Home/Index/0 (Accessed: 25 March 2024).

Week 9 Project Management

Visit to Talbot Rice Gallery

I observed the exhibition titled “Talbot Rice Residents” and talked with a curator of Talbot Rice Gallery as field work from the course. Artists selected as Talbot Rice Residents receive year-round curatorial and technical support from the Talbot Rice team, as well as access to the University of Edinburgh’s extensive academic and interaction with the vast academic community within it, including access to workshops, libraries and collections (Trans Artists, n.d.). I think that this community-building institutional linkage can adopt participatory methods that encourage co-creation and shared ownership of cultural narratives. Moreover, by working with local partners, they can recognise the cultural and social dynamics specific to each area and tailor their curatorial practices to the unique circumstances and needs of their communities. Additionally, residents are encouraged to utilise the resources provided and engage in long-term research, as well as actively seeking out opportunities to showcase their work in both real and digital form throughout the programme (Trans Artists, n.d.). Through this, they are enabled to explore all artistic practices and curatorial possibilities.

Photo taken by the author

Photo taken by the author

Photo taken by the author

My Curatorial Project

Apply the participatory methods and site-specific curatorial practices by the community learned during the gallery visits to my own project. Firstly, community participatory methods are effective in working with Bristol’s street art community to organise events such as artwork photography tours and art workshops. This allows the local community to participate in the archiving project and enjoy the discovery and creative activity of the artworks. Site-specific curatorial practice working with local partners should also be achieved through the provision of educational programmes on the history and culture of street art. I would like to offer educational programmes on the history and culture of street art in schools and community centres in Bristol. To provide students and local people with an understanding of how street art has influenced society and culture in Bristol, and to engage them in archiving projects.

Week 8 Site

Reflection of the lecture and my curatorial project

The lecture considered how the qualities and layers of space/place add to, interact with and shape the work. Primarily, places were categorised into the physical aspects of space and the layers of historical context and use, with my project focusing on the latter aspect. Street art has a strong relationship with the cultural aspects and history of the city, such as street culture. Hughes (2009) describes street art as an inclusive and diverse artistic expression in an urban context directly derived from the graffiti revolution. Powers (1996) indicates that graffiti was often an imitation of hip-hop culture and that it attracted the most media attention of all elements of the hip-hop subculture in New York. Therefore, it can be argued that street art has aspects of street culture inherited from graffiti. In addition, street culture shares space with diverse disciplines, including anthropology, art (both art history and visual arts), community social work, criminology/criminal justice, cultural studies, fashion, film studies, human geography, popular music studies and sociology (Ross et al., 2020). The ‘street’, the space occupied by these disciplines, is an independent entity where people live, move and sometimes work, as it refers to a specific site as a living cultural collective, and within the boundaries of the street a myriad of economic, political and social activities and interactions are found. I think that the themes addressed by street art have a deep connection to this site of the street.

Moreover, a process-oriented approach to street culture releases the essentialised, singular or static notion of spatialised culture into its place and instead understands street culture as a spatialised connection point between a broader series of flows. If the space in which street art is installed is represented as part of a fluid and open public space, it can be conceptualised as a ‘site (stay)’, a public space in which people can stay, interact and develop different activities. (Massey, 2005) Accordingly, street art in public space should be in a space that is accessible to everyone because it belongs to that place. For street art, the concept of site is one of the crucial elements for its authenticity.

Week 7 Achieving/ Field trip in Glasgow

Reflection of field trip to Glasgow

In a gallery talk in which the audience viewed an exhibition that displayed and reinterpreted the Hunterian Art Gallery’s collection of African art, the curators stated that the purpose of the exhibition was to ‘unpack and mix objects to create an opening to start a new conversation’. This means they are challenging the theme of how African art has been categorised by Western institutions and how it can be understood differently (Hunterian Art Gallery, 2024). Excavating the archive, re-labelling it and bringing it to the exhibition space can provide an opportunity to rethink long-suppressed voices. Mulvey (2011) states that such archives can frustrate colonial discourse by showing a kind of traditional impression derived from imperialism’s blind spots, but a reality overlooked by its perpetrators. Curating the archive, like the intention of this exhibition, could provide room for new conversations and meanings to fixed discourses and impressions.

Photo taken by the author

Photo taken by the author

Photo taken by the author

My Curatorial Project

Archiving Street Art

My Curatorial project challenges the preservation of street art, which is characterised by its transience, by digitising the archive of street art and posting it online. Street art is a temporary element that constantly changes the appearance of the city and their placement in outdoor public areas can cause them to change and disappear through deterioration, decay or deliberate interventions such as painting, polishing or removal (Hansen, 2018). This makes street art crucial to maintaining its authenticity, and storing archives online could lead to the loss of the original intent of the work. However, online archives, like this temporary street art, are difficult to keep permanently, and we consider this to be another temporary platform. Glaser (2016) describes street art, with its temporary qualities, as a ‘zombie’, and digital archives are at the intersection of life and death and argues that it can inscribe an intermediate stage between destruction and temporary rebirth in a project. The fact that digital archives can be adjusted temporarily or anti-permanently by their providers makes it possible to preserve the transitory qualities of street art without completely erasing them.

Week 6 Publishing as curatorial practice

Lecture Reflection

The lecture discussed publishing as an artistic practice. This publishing is where the a kind of “indie publishers collective imagination” (Hindley, 2019) emerges. As such, it allows people to explore artistic territories and capacities and start conversations about new possibilities from texts gathered from all kinds of arts stakeholders. The best thing about publishing is to dig into the tricky and complex questions and articulate them in a way that people can relate to and engage with (THE MUSEUM OF LOSS AND RENEWAL, 2022). Themes and issues that are touched upon in art practice can be discussed in depth in a publication. In addition, publications have a role to play in the excavation and reinterpretation of memories, such as an archive, and the GIVE BIRTH TO ME TOMORROW festival produced a publication to preserve and revive the emotional changes of the moment (Benmakhlouf & Taal, 2021). To document in a publication is to recall and revive in writing how they contributed and practised in many processes.

For my curatorial project

Having said that the advantage of publishing is that it can explore complex questions and express ways in which people can empathize and engage (THE MUSEUM OF LOSS AND RENEWAL, 2022), I think that my interest in street art is that the work itself takes on a ‘publication’ like role. In the first place, street art is integrated into the context of each locality and contains important topics that contribute to the public space (Di Brita, 2019). In other words, street art provides an opportunity to discuss the topic of social and political issues in the area to which the artwork belongs, and thus to an unspecified number of people. By exposing them to the public space, people are implicitly encouraged to reach out to them and actually start a conversation or discuss the subject on the internet. Furthermore, as street art usually has a strong association with the city whose walls it depicts, the people around it often share common themes and issues; according to Bertasa et al. (2021), street art often has social concerns chosen as the subject matter of the work. Thus, street art can be considered to have the same strengths that publishing has in presenting a controversial subject and giving people the opportunity to respond to it and have a conversation.