Week 9 Visit Talbot Rice Gallery

Sammy Baloji’s Untitled (2018 / 2023)

Firstly, James introduces us to Untitled (2018 / 2023) by Sammy Baloji. He is an artist working in Brussels, but he is also from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, as is his work.Sammy combines 50 copper cartridge cases (many of these are authentic World War I cartridge cases, some even dating back to around 1960) with potted plants from the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The artist wanted to use these objects to tell the story of how a European went to Africa, which they saw as a rich source of materials, such as copper, to develop industry, or even to expand their army, for example. At the time I didn’t really understand why these cartridge cases and potted plants were a demonstration of, or even a critique of, the issue of ‘debt’. Until I read through Talbot’s website that it was because tens of thousands of Africans had died under the barbaric regime of the Belgian king, but that Belgium’s debt from the vast wealth accumulated under subsequent colonial rule was the subject of the country’s recent BLM protests. To me, the bronze seems to represent the weapons in the hands of some of the colonialists, and the greenery seems to be the hard-working oppressed people of that land, people who tenaciously lived in a land that was brutally ruled. The presentation of these artworks seems to remind us that there is still resilience and growth under the oppressive structures of domination. Returning to the question posed before the exhibition, can I feel the emotion? The answer is yes, after understanding the context in which they were created, I can feel the complex emotions of unfair relationships, the confrontation between civilisation and nature, the uncompromising and defiant spirit, the stubborn vitality and so on.From the curator’s point of view, the area of the gallery where the works are displayed became a consideration, and James explains that as the plants are from a hot part of the world, it was important to ensure that they survived the exhibition by ensuring that they had access to sunlight, so the works were placed in a bright and open space.

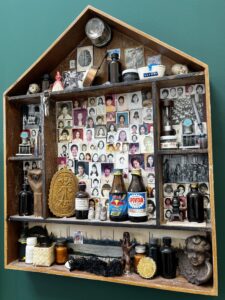

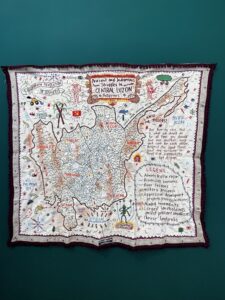

Cian Dayrit

Next, there are tapestries hanging on the walls, some sculptural pieces (similar to helmets) and a series of collectibles created by Cian Dayrit. In the concept of these works, I could clearly see the map of the Philippines or the elements of space so to speak. Through the introduction, I learnt that the collection takes the form of maps, artefacts and shrines, and incorporates elements of people in politics, culture and economics. Through the introduction and my search for information, I learned that one of the works is a tree of life in a state of decay and rebirth. This image again extends upwards in branches, each of which is in turn labelled imperialism, capitalism and so on. The unevenly broken branches contain the conditions for the growth of imperialism and capitalism, such as cheap labour, militarisation and genocide. The artist visualises the development of this feudal system in a kind of ‘flow chart’, showing the viewer the ‘debt’ of the Philippines arising from capitalism.

Figure From Talbot Rice Gallery Website

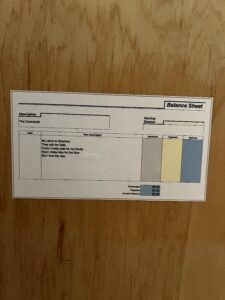

Lubaina Himid‘s Naming the Money

The final piece is Naming the Money by Lubaina Himid, the largest work in the Talbot Rice Gallery. The artist has painted and cut out historical paintings of enslaved Africans from European royalty and placed them in the venue to music. On the back of each figure are their names, with the difference that they have two names, one of their own and the other given to them by their owners. Moreover, there is a ‘balance sheet’ behind the figures. The artist is reclaiming the original humanity and different identities of these figures by creating an entire work. During my visit, I also saw that some of the figures have puppies and some have flower pots, which are all storytelling. Viewing the artwork from a global perspective, it was as if the figures came to life, seemingly in conversation and dancing to music. The artwork is linked to a long history of dispossession, expulsion, colonisation, etc. of these people by the nobility in the past for profit, which has to be considered. The enslaved people of the past went to plant and farm, they were heavily indebted, and aren’t the contemporary people who are heavily indebted also oppressed by capitalism?

Recent comments