In the age of declining individualism and categorical identification, Rooney’s Normal People supposes that the answer to the question of contemporary identity lies in an intersubjectivity which may only exist in the intimate relation between two people. While other authors we’ve discussed focus more on the relation of society to self, Rooney identifies the plane on which people exist from day to day: that of the personal relationship. Her characters reflect that the intimate relation of two people, containing as many similarities as differences, can be instrumental in the construction and development of oneself.

For much of the novel, Marianne and Connell understand their lives largely in relation to one another. While each character grew in their respective paths, the perception of the other was critical in the validation of said growth. The novel begs the question: is the truest form of self-knowledge that which we can find in another person?

Their relationship, as a means of defining existence, acts on two, sequential levels. First the definition of the other; and second, the existence of the defined self within the other. The contours of each person form the boundaries of similarity and difference, allowing each other to understand the boundaries between self and other. As the two come to know themselves, they can share the priceless experience of knowing and sharing aspects of themselves within the confidence of their relationship. Simply, the successful completion of a process of identification and relation.

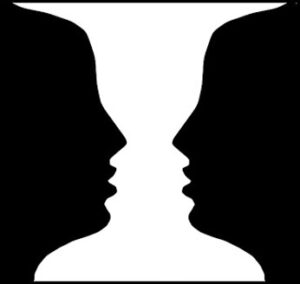

Visually, we can imagine this relationship as the Rubin’s Vase illusion, or the figure-ground phenomenon in which two images, defined in each other’s related positive-negative space, exist simultaneously.

The image, at once, contains two discrete objects. However, these objects are only identifiable to us due to the presence of the other, offering a photo-negative which defines the lines between the two. Whichever you perceive first does not matter; nonetheless, each is foundational in our understanding of the other. However, the objects are not related merely in their opposition. The existence of either-or is defined by a shared line, a boundary, in which both objects meet and exist in harmony. Normal People is our larger image, and the picture embodied by Marianne and Connell is as much characterized by their differences as their commonalities, bringing into relief the ultimately real coincidence of life— that yourself, your life, is both your own and something which lives in the lives of the other. [1]

As such, the pair exist as both a defining complement of the self, as well as a discrete unit of existence. Marianne contains elements of Connell; Connell, Marianne; and together, they—and their relationship— exist as an entity alone. That is, insofar as intimacy between people—sexual, emotional, or otherwise—produces an enigma which experiences triumphs and challenges itself.

“He has sincerely wanted to die, but he has never sincerely wanted Marianne to forget about him. That’s the only part of himself he wants to protect, the part that exists inside her.” (255)

“But in the end, she has done something for him, she’s made a new life possible, and she can always feel good about that.” (272)

Rooney demonstrates in the on again-off again nature of Marianne and Connell’s relationship, in which they often lead their own lives separate from each other, yet are irrevocably influenced and experienced by the gifts (if you will) that they have given to each other (i.e., Marianne’s capacity to identify and receive love, or Connell’s confidence in pursuing writing seriously). In addition to their individualities, Marianne and Connell’s “single-pot” relationship, the private intimacy and vulnerability they share, evolves as a result of shared experiences within their lives.

The notion of the ‘completion of the self’ is one which, by my telling, has its literary roots in Plato’s Symposium, wherein Aristophanes describes the primeval notion of soulmates[2], described as a series of three hermaphroditic globes halved, creating for each modern man and woman a doubling of itself which, when united, would create a larger whole.

“And so when any lover is fortunate enough to meet his other half, they are both so intoxicated with affection, with friendship, and with love that they cannot bear to let each other out of sight for a single instant… although they may be hard out to say what they really want with one another… The fact is that both their souls are longing for something else… and so all this to-do is a relic of that original state of ours, when we were whole.”

To briefly indulge in sentimentalism, Rooney’s assertion is, in my view, the most real, and most touching of all representations of self discussed this term. The painful reality of life is that our lives are not merely our own. It is a difficult reconciliation that we need other people, intimate relationships, to understand ourselves. Our existence, as members of a society, is contingent on our existence within the hearts and minds of those who live among us. Connell and Marianne, plagued with problems as they are, embody an unconditional love most hope for. The façade of image which permeates the cultural dialogue (and most other books we’ve read) is discarded in Rooney’s depiction of the two. They exist in a state of mutual understanding in which the veil of projection falls away, enabling a true vulnerability, and in that vulnerability, self-knowledge.

__

[1] I would also like to note that, in this comparison, any person who is an ‘other’ can act as the negative/positive image of the other—it doesn’t necessarily need to be Marianne/Connell. Their existence isn’t contingent on the other being Marianne/Connell, but merely an ‘other’.

[2] I would argue against the notion that Marianne and Connell are Aristophanian ‘soulmates’, in that they are not so much completed (in themselves) by the other, but rather defined by this counterpart. But this is a tangent that I have elected to omit from this post.