Alexandra Kleeman’s You Too Can Have A Body Like Mine explores the psyche of A, a young woman trapped in a simultaneously internally and externally claustrophobic world. The characters within her life often permeate her selfhood, and in her view, threaten to consume her.

Interestingly, Kleeman chooses to abandon names in favor of single letters, particularly A, B, and C. In this, both reading and writing about the relationships becomes an exercise in a logic game reminiscent of the domain of analytic philosophy. A is related to B in X manner; A is related to C in Y manner; does B relate to C, and if so, how? In a logic equation, B is defined by its differentiation from A, directly correlating to one of the primary tensions in the novel.

A’s definition of herself is characterized by a confusing matrix of physical attributes, material belongings, and psychological dynamics. The novel begins with B’s decision to cut her hair to the length of A’s, destroying one of the final remaining traits distinguishing the two characters superficially. This distresses A, as it is one of many actions taken by B to assume A’s selfhood. Another source of self-definition, and thus distress, in A’s life is her fraught relationship with C. C claims to know her but also know what’s best for her, though A feels all but truly understood by him. C’s relationship with A is largely subject to his own subjectivity, rarely engaging with her in any essential manner. Yet, once this relationship ends, A finds herself unable to move through her life without the presence of him. The novel moves through this web of perpetual misunderstanding to examine what exactly constitutes the self and how oneself can relate to the outside world.

A exists in a world of mirrors, reflecting different images of a seemingly intangible reality. Like a carnival funhouse, A moves through the landscape of the novel forced her to confront these varying reflections, none of which seem to properly register and only serve to further alienate her from a sense of real self. But rather than shove through to the other side, A elects to smash all of the mirrors, turn the lights out, and flee for the Church of Conjoined Eaters.

It seems that the social presence of others and the self’s relation to them is the substance which fuels the novel’s community: B defines herself by the likeness of A; A requires the recognition of C; A resents the perceptions projected on her by B and C, so A joins a Kandy Kake cult.

A’s journey begs the question: does the existence of multiples/excess diminish the value of a single unit? Applied to You Too, does B’s existence, as she attempts to assume the traits of A, devalue A herself?

If we apply the conventions of economic consumption to the consumption of the individual, the answer would be plainly, yes. Increases in supply (A and B, a supply of two of the same product) not precipitated by increase in demand decrease value. Individuality, uniqueness—these are the virtues of a consumed commodity. Of course, it is grossly demoralizing to economize such a nuanced thing as human beings, but this commodity-value based logic permeates the book repeatedly.

A often references her decided lack of ‘excess’, noting that as much as she would like to trim off pieces of herself to give away to B and C, she cannot do so without compromising herself. In this, A constructs her body and spirit as a sort of non-renewable resource—a definite body and ego which withers away as it gives parts of itself with others. However, the issue lies not in any issue of ‘supply’ or ‘excess’, but rather that the means of defining oneself are inextricably tied to an external perception of oneself as unmistakably distinct.

As a resolution to the matter of reconciling the self relative to the other, Kleeman opts for self-abnegation. A abandons the hope of maintaining herself as an individual discrete to B or C to join the ghosts of the Church. In choosing this avenue, Kleeman embodies the end result of rapacious reproduction observed by Walter Benjamin in “Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. “Its self-alienation has reached such a degree that it can experience its own destruction as an aesthetic pleasure of the first order,” Benjamin writes.

Kleeman’s work raises but fails to answer a question also raised by Berger and his contemporaries: In social relations (and their abstractions in art), what does it mean to truly know and be known, see and be seen, and act and enact action?

___

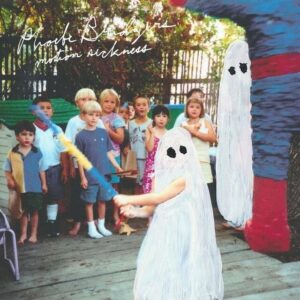

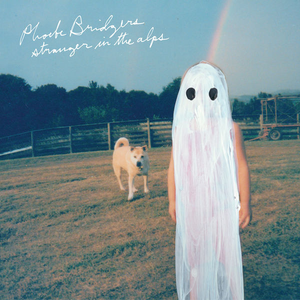

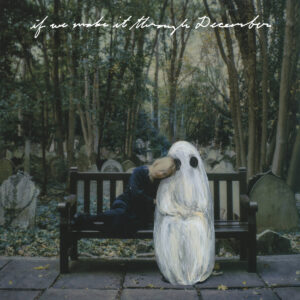

Brief aside– when I was reading the bits about Wallyheads and the concept of ‘ghosting’, I couldn’t help but think about Phoebe Bridgers’ use of ghosts in her visuals, especially in the artwork for her first album:

Even to those who don’t know the context of the images, it is impossible to extract the ghosts as separate entities from the situation in which they exist. Rather, they become more glaringly apparent as they stand apart from the realistic background images.

Like her music often suggests, people move through the world in entirely different experiences, though they may be in the same physical places. One person may be experiencing a party, walking through a field, and another may feel like a shell of a person, a ghost. In You Too, Kleeman’s ghosts/Wallyheads also walk around among the real world, though they are in a much more real way, somewhere else. They speak in unfamiliar tongues and lack the self we attribute to ‘normal people’.