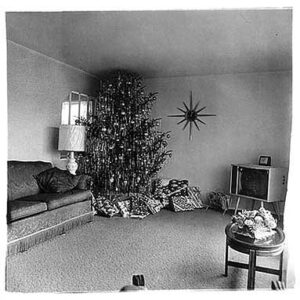

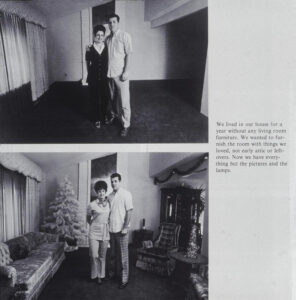

This week I have found several photographs depicting living rooms decorated for Christmastime by well-known American photographers–by Chauncey Hare (Interior America: West Chester, Pennsylvania, 1971), Diane Arbus (Christmas Tree in a Living Room in Levittown, 1963) and Bill Owens (an untitled image from his book Suburbia, 1968-1970). All these photographs together have one thing in common–namely, a sense of determined, desperate cheer. People are desperate to decorate their interiors with blithesome ornaments that will hide the desolation that they feel, the desolation of their surroundings, the terror of the future, or the loss they know is coming. Many families struggle with different types of problems throughout the year, but Christmas imposes a special pressure on everyone to bury their problems with Christmas decorations and a merry atmosphere. The Christmas adornments in the photographs seem forced into the families’ homes. They do not fit in with the rest of the interiors. The pictures make it obviously clear that these people’s lives are in fact sadder, more disappointing, darker than how the Christmas decorations strive to make them out to seem. What I would like to address in this project is how far families are willing to go to keep up “the Christmas spirit” that is in conflict with their real feelings and pains.

A similar tension is in some well-known pieces of literature. For instance, O. Henry’s short story “The Gift of the Magi’ narrates one episode in the life of a young couple each of whom are so poor that they must sell the most valuable thing they own to be able to buy the other a Christmas gift. She sold her hair to buy a watch chain for her husband. Without knowing it, he, in turn, sold his watch itself, his dearest possession, to get hair combs for her. Like in my grandfather-and-too-much-beer story, the gifts were to create the illusion of happiness during Christmas but they only exposed and aggravated the couple’s profound poverty (of course, the gifts also demonstrated their devotion to each other).

The contrast between expectations people have about Christmastime and its reality is also clear in the well-known story “The Dead” from The Dubliners by James Joyce. At the end of a dinner, the protagonist Gabriel learns from his wife that she spent the evening a little aloof, thinking about a boy who loved her and died when she was young. Gabriel gets angry precisely because Christmastime is a moment when people desperately crave affection, a sense of togetherness, and are filled with nostalgia. In the middle of the most cheerful time, she didn’t share his delight and nostalgia, thus acknowledging the darker and tragic aspects of their marriage.