Visited 06/10/20.

One room exhibition in the basement of City Art Centre. Varied collection (although almost all 2D work) and I enjoyed looking around. One annoying attendee playing a loud game on her phone. Family of gingers also in attendance.

https://www.edinburghmuseums.org.uk/whats-on/bright-shadows-scottish-art-1920s

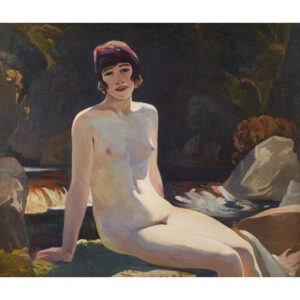

‘Cecile Walton at Crianlarich’, Eric Harold Macbeth Robertson. Oil on canvas, 1920.

This piece is new to the gallery and as such was made the “face” of its ‘Bright Shadows’ exhibition. The hair, hat and build of the lady pictured certainly do scream 1920s so you can see why they chose it. In the gallery the accompanying information describes how this piece was scandalous and revolutionary for its time as the lady is painted nude in a relaxed, outdoor environment, she seems comfortable and in control, staring towards us, and indeed the sitter was the wife of the artist. I’m personally in two minds about the piece. While it is refreshing to see a nude where the lady seems relaxed and real, to me this still feels nude rather than naked. The sitter is deliberately posed, and even if the pose is relaxed this jars in my mind with the idea of her having more control. It also got me thinking about the exhibition of the piece and its use in promotional materials, particularly posters hung up around the city. To me, this doesn’t seem like a moment that was intended to be put on display to the public. Her body centres the piece, your eyes drawn to her flesh before even her face. It feels like a holiday snap, a moment shared between lovers, with the woman’s body admired under the males gaze. I wonder if she thought, while she was modelling for this painting, that her body would be used to advertise a City Art Centre exhibition 100 years later. The pair also divorced 7 years after the creation of this painting, with both of their careers falling apart shortly after and Eric turning to alcoholism. This piece perhaps then represents the bitter sweet happiness of the past, its resurfacing a little sad.

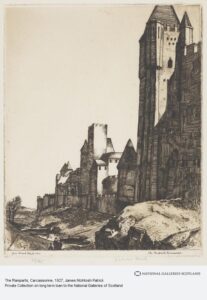

‘The Ramparts, Carcassonne’, James Mcintosh Patrick. Lino print on paper, 1927.

Really liked this piece in person – less so when viewing online.

‘The Pink House’, 1928 and ‘Iona, Mull and Ben More in the Distance’, 1929. Samuel John Peploe.

Peploe was one of the four Scottish Colourists – along with Cadell, Fergussen and Hunter. My favourite of the two pieces was ‘The Pink House’ because I found it really evocative of the feeling of being in a warm foreign street, on holiday and feeling free.

“The Scottish Colourist S.J. Peploe was first introduced to Iona in 1920 by his friend and fellow artist F.C.B. Cadell. He proceeded to return to the island almost every year until his death in 1935. The peaceful atmosphere offered him a sense of freedom and mental rejuvenation, while the brilliant white beaches proved an enduring source of inspiration. Peploe’s paintings of Iona cemented his reputation during the 1920s, and still remain among his most iconic works.

Rather than depict the grassy southern end of the island, the artist favoured painting in the north, taking advantage of the views towards Mull. He often worked outdoors, sometimes in a single sitting.”

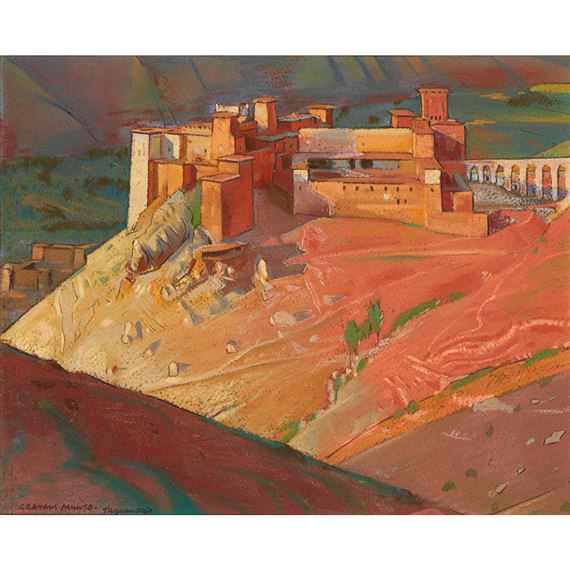

‘Kasbah Taguendaft, Morocco’, Alexander Graham Munro. Pastel on paper, 1920s.

This was my personal favourite piece in the exhibition. It is very beautiful in real life, the colours are absolutely gorgeous and the landscape dreamy, foreign, hidden in hills, mysterious and like something from a story.

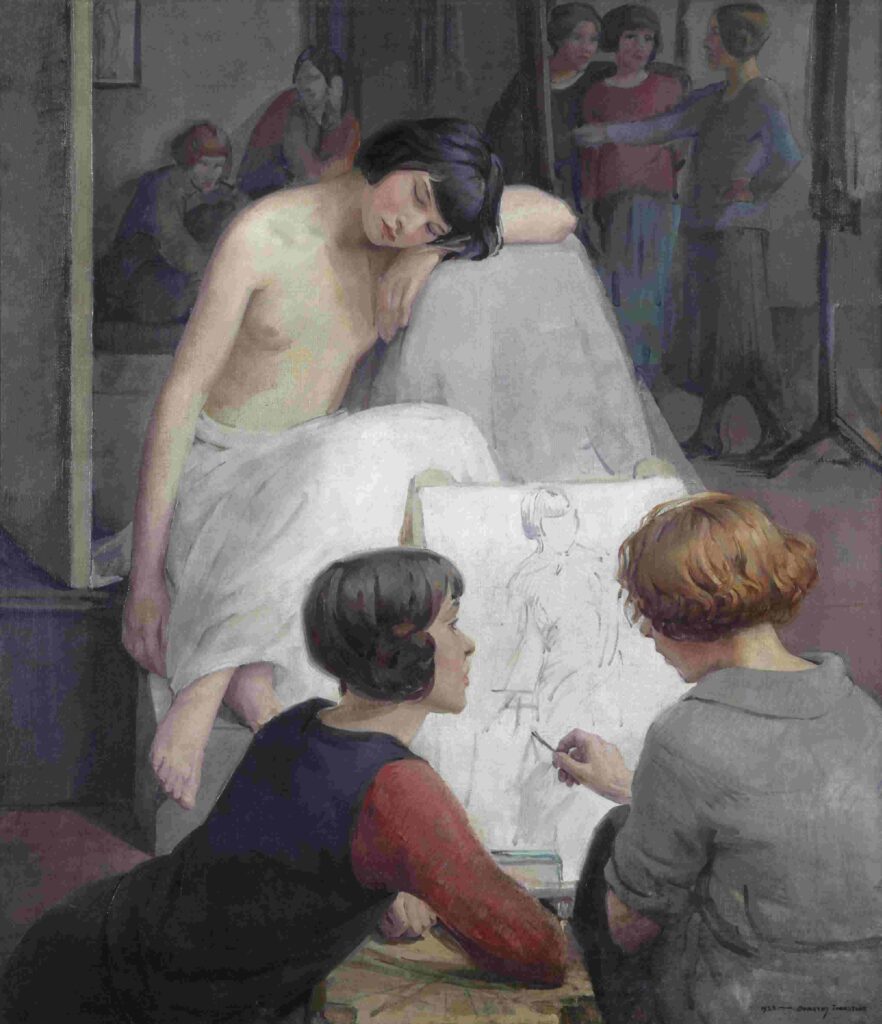

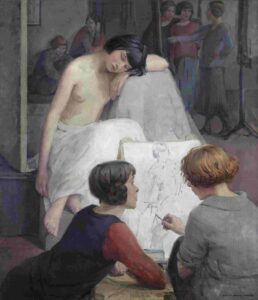

‘Rest Time in Life Class’, Dorothy Johnstone. Oil on canvas, 1923.

“Dorothy Johnstone was just 16 when she enrolled at Edinburgh College of Art. Having excelled as a student, she joined the college’s teaching staff in 1914.

This painting offers a glimpse into one of Johnstone’s classes. A life model is shown taking a break from posing, while students discuss and refine their compositions. Johnstone herself appears in the top right corner, working at an easel.

Rest Time in the Life Class was displayed in 1924, the same year that Johnstone married the artist D.M. Sutherland. She was subsequently obliged to resign from her teaching position, as married women were barred from holding full-time posts. Although opportunities for women artists slowly improved during the 1920s, discrimination remained common.”

I liked the accompanying study portraits, and was interested by the story of the young artist at ECA.

‘Spring Morning’, David Gauld. Oil on canvas, 1927.

I was really drawn to this piece in the gallery. I liked how washed out the colours were, which, combined with the outskirtsy subject, made the scene appear dreamy and forgotten. I also liked the large scale, and found the choice of frame interesting (large, antiquated and brown).

“David Gauld is one of the lesser-known artists associated with the Glasgow Boys. During the 1880s and 1890s he was one of the innovators of the group, creating illustrations, paintings and stained glass designs with a strong Symbolist aesthetic.

Spring Morning is characteristic of his later work. Gauld was drawn to semi-derelict buildings in rural locations, and painted many such scenes of farmhouses, barns and mills glimpsed through trees. The setting of this picture has not yet been identified; it could be somewhere in Scotland or France.

Gauld was elected as a full member of the Royal Scottish Academy in 1924. This canvas was exhibited at the Academy’s annual exhibition in 1927.”

‘Daydreams’, Francis (Fra) Henry Newbery. Oil on canvas, 1920.

“a painter and art educationist, best known as director of the Glasgow School of Art between 1885 and 1917. Under his leadership the School developed an international reputation and was associated with the flourishing of Glasgow Style and the work of Charles Rennie Mackintosh and his circle. Newbery helped commission Mackintosh as architect for the now famous School of Art building and was actively involved in its design.

Born in Devon to a shoemaker and his wife, Newbery went to school in Bridport, Dorset where he qualified as a teacher, and later as an art master. While working and studying in London he won an ‘Art Master in Training’ scholarship in 1881.

At the Glasgow School of Art he was a vigorous and innovative headmaster. He gave teaching posts to practising artists rather than relying on certificated art masters. He established an art club allowing students to branch out from the national art school course, and employed several women teachers, unlike most other UK art schools of the time. Newbery established craft workshops and introduced embroidery classes where his wife, Jessie Newbery, played an important part. Overall, he wanted students to have a strong training in traditional techniques, while developing their unique individual talent. His own painting was associated with the Glasgow Boys‘ and he was close to James Guthrie and John Lavery.”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francis_Henry_Newbery

Fra just seemed like a cool dude. He advocated for greater gender equality in arts teaching, and the Newbery family are apparently interesting artists.