Blog by Mélina Valdelièvre, Lead Specialist (Racial Equality), Education Scotland

This post is part of a series of three blogs by educators and activists published in February 2023 and focusing on the Building Racial Literacy (BRL) programme. You can see all the blogs in the series at the link below:

Building Racial Literacy programme blogs

Funded by the Scottish Government’s programme of work on Anti-Racism in Education, the Building Racial Literacy professional learning programme was co-designed by members of the Scottish Association for Minority Ethnic Educators, the Coalition for Racial Equality and Rights, ScotDec, Third Generation Project, the University of the West of Scotland and Education Scotland.

When, as a co-design group, we first started envisioning the Building Racial Literacy (BRL) programme in 2021, we set the long-term goal of making anti-racism a baseline professional value. While social justice is already a baseline value for the General Teaching Council for Scotland (GTCS) professional registration, our emphasis on anti-racism came from the acknowledgment that anti-racism is not a widespread standard of behaviour and practice in education. Yet the experiences of children, young people, educators, families and wider communities remind us that racism in Scotland is very much alive and well. In 2020, the DFM met with children and young people to listen to their concerns. Following the death of George Floyd and the increased momentum from Black Lives Matter, the Scottish Government received over 1,000 pieces (see p. 92) of correspondence asking for race equality and black history to be taught in Scottish schools.

Collaborative design also ensured that the programme was informed by anti-racist expertise, knowledge of the education professional learning landscape and the educators with lived experiences of racism. By drawing on some of our lived experiences and unpacking them from multiple, critical lenses, we were able to design authentic, meaningful and inclusive professional learning experiences. Drawing on the Teaching in a Diverse Scotland reports (2018 and 2021), which call for greater racial literacy across the education sector, we set out our BRL vision:

“a Scotland where educators are no longer ‘race evasive’ (i.e. avoiding acknowledging race and talking about racism) and where they are empowered to identify and implement anti-racist behaviours and processes in their everyday practice.”

Leading the BRL programme has been the most rewarding professional experience of my career.

Our Creative Reporter, Hannah Moitt, has captured the story of BRL so far with two short animated videos, Part 1 for our first cohort and Part 2 for our second cohort. The reflections of past participants Karrie and Arnault provide examples of how enriching this experience has been. Hearing from participants about the impact the programme has had on them personally and professionally never ceases to amaze me (check out Gemma, Angel, Chereen and Katie). Being the BRL Programme Lead has drawn the attention of both haters and lovers, and I’m grateful for the invaluable support of my colleagues in Education Scotland’s Professional Learning and Leadership team, and beyond, who have helped me rise back up when I faced lows and cheered me on.

Since January 2022, we welcomed over 300 educators and education system leaders across Scotland onto BRL and watched them grow with the emotional rollercoaster of learning and unlearning. For many participants, it is the first time they stare straight into the eyes of the insidious beast that is racism. That first stare is always unsettling, especially when we see parts of ourselves in that beast. It is tempting to look away, pretend it doesn’t exist and just give up. But the programme works when participants keep on looking at the beast of racism and still feel inspired, and committed to anti-racism, knowing it’s just the beginning but equipped with what they need to continue the long journey ahead. We remind them that racism took centuries to build, so don’t expect it to be dismantled overnight.

In the BRL poem, ‘Seeds of Antiracist Education,’ Tawona Sithole writes about the programme:

“inclusive and supportive

where it’s ok not to always stand tall

where it’s ok not to always stand at all

sometimes we have to stumble a little

real is ok but i kinda like the surreal

where we take those stumbling blocks

and we turn them into building blocks”

What is it about BRL that turns those stumbling blocks into building blocks? In the second part of this blog post, I outline some of the critical questions, possible solutions and reflections that led to the content, structure and ethos of the BRL programme.

First of all, how do we ensure that BRL doesn’t reproduce racist processes and outcomes?

There is no easy answer to this one and it is something we need to keep checking. Because of the complex, systemic nature of racism, even the best intended “anti-racist” actions can lead to unintended, racist consequences. With a high profile anti-racist professional learning programme funded by the Scottish Government comes several risks we have to keep in mind. BRL should not become a tick-box exercise or a CV asset that benefits more white majority ethnic educators than Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) educators in Scotland. To mitigate the risk of BRL boosting the career progression of white participants on the programme more than BAME educators who aren’t on the programme, we used positive action, allowed under the Equality Act 2010, to prioritise BAME applicants. BAME teachers are under-represented in Scottish education, especially in promoted posts, and it was important that BRL did not become yet another barrier to their career progression. Moreover, as a BRL participant once put it, “just because I am Black does not mean I am racially literate.” BRL can help BAME educators make sense of their racial identities, providing vocabulary to articulate racialised experiences, opportunities to unlearn internalised racism and tools to navigate racism. For some educators of colour feeling isolated in their workplaces, BRL connects them with support networks to rely on when dealing with future race-related stress and issues. These tools and networks play an important role in the retention of BAME teachers in Scottish education. The BRL programme has made educators of colour feel empowered and liberated, as Rukhsana explains in her blog:

I have lived for too many years trying to blend in, hold back and keep my head down. (…) I will not be quietened. Mujhe suna jaye ga. I will be heard. Mujhe dekha jaye ga. I will be visible. I have a renewed sense of power, motivation, hope and positivity.

For all participants, it becomes clear that BRL is a challenging course that, for many, leads to deep personal and professional transformation and it is only the beginning of a longer journey of anti-racist learning.

We support both current and past participants to continue learning and reconnecting and, with the feedback they give us, we are able to evaluate and improve BRL to ensure it doesn’t reproduce racist outcomes. When participants create personalised anti-racist action plans at the end of the programme, we encourage them to think critically about the potential unintended outcomes of their actions as well as the intended outcomes. For example, a teacher early on in their journey might want to raise awareness of racism with texts that include racial violence. That teacher should consider 1) how best to safeguard learners in an age and stage appropriate way, and 2) whether the texts create narratives that reinforce racism, such as white saviourism. If they don’t then there may be unintended outcomes of learners experiencing racial trauma and learners internalising implicit biases (in the case of white saviourism, the message that people of colour are powerless victims who need to be saved). Just as we evaluate BRL extensively with a range of case studies and evaluation forms before, during and after the programme, we get participants to consider how they will know whether their actions are successful and how they can remain accountable for their outcomes.

Second of all, we asked ourselves, what do we want the experience of learning on BRL to feel like?

We were determined that BRL should take cognisance of the comfort of BAME participants, especially of Black participants and participants of colour. In the past, I have seen many race equality workshops which focus predominantly on the comfort of white people in learning spaces, spending a lot of time explaining “BAME” identities but forgetting to include “white” as an identity to be explored. Being a learner of colour in such workshops can be, at best, uncomfortable. Drawing on my own experiences as an educator of colour, I knew that, too often, it is up to the only person of colour in a workplace to explain racism to white colleagues. Not only can it be exhausting if racial microaggressions are a daily occurrence, but the interactions with colleagues can be tense and, at worst, they can cause racial trauma. So the last thing we wanted was for BRL participants of colour to feel they had to do all the emotional labour of explaining racism to white BRL participants, risking racial trauma.

The racial dynamics and power dynamics that exist in learning spaces must be considered when designing an anti-racist professional learning programme. It needs to be acknowledged that learners do not experience learning spaces equally and those power imbalances can stifle learning. With between 80 – 140 participants per cohort so far, we were able to assign each participant to three different types of learning networks: racial affinity groups (based on self-identified racial-ethnic identity), professional affinity groups (e.g. headteachers together) and regional affinity groups (e.g. Edinburgh participants together). Taking collaborative learning as a central component of the programme (in line with the National Model for Professional Learning), we considered how we could minimise power imbalances by using these groups for different discussions and collaborative tasks. As a result, many participants leave the programme having access to a range of strong support networks to rely on as they move forward in their anti-racist journeys – a desired positive outcome that emerges from programme evaluation.

In light of the emotional experiences, support networks play a crucial role. Support networks are worth their weight in gold, one of our Compassion Captains often reminds us. BRL Compassion Captains are counsellors who add an extra layer of support for any participant who might experience emotional distress or racial trauma triggered by the content or discussions on the programme. Having Compassion Captains on BRL is essential, because learning about racism cannot just be an intellectual exercise (as noted by Rowena Arshad in her latest blog). I am reminded of the African American scholar, Sandra Chapman, who told me what mattered most to her for racial dialogue to work:

Race is an emotional topic and we must create spaces where this emotion can exist. When we stifle or encourage people to be stoic about race in education, we make it an intellectual exercise. We need students and adults to feel the emotions in their heart, not just process things in their brains, in order for people to be motivated to create change in their communities.

To answer the question, what should BRL feel like? We wanted it to feel like a safer, braver learning space where those emotions can be acknowledged and, hopefully, where healing can take place. One participant shared her experience of BRL as a safer, braver space which was validating and supported her healing:

I listened to the aims of the course and found myself already crying. So much so that I during the break I needed to go wash my face. Just the simple act of acknowledging some of the experiences that I thought were unique to my life was overwhelming. (…) Being in group discussions with others specifically grouped with me for their racial identity gave us a safe space to realise that we always silenced ourselves because the systemic nature of racism made us feel like a nuisance when we brought up race.

From the personal reflective journals participants keep, the powerful stories, counter-narratives and lived experiences they witness, to the multiple and diverse perspectives each of them bring to the programme’s growing content, BRL has touched the hearts of all who engage with it. At the beginning of the programme, I set the tone with my welcome speech where I explicitly acknowledge the power dynamics and the diversity of participants, naming a range of often marginalised identities that we warmly welcome. The handful of people who are so used to pretending not to see difference feel uncomfortable about this. But the majority of participants feel seen – even comfortable with their dyslexia for the first time as one of them later told us – and many feel emotional for being accepted for who they are.

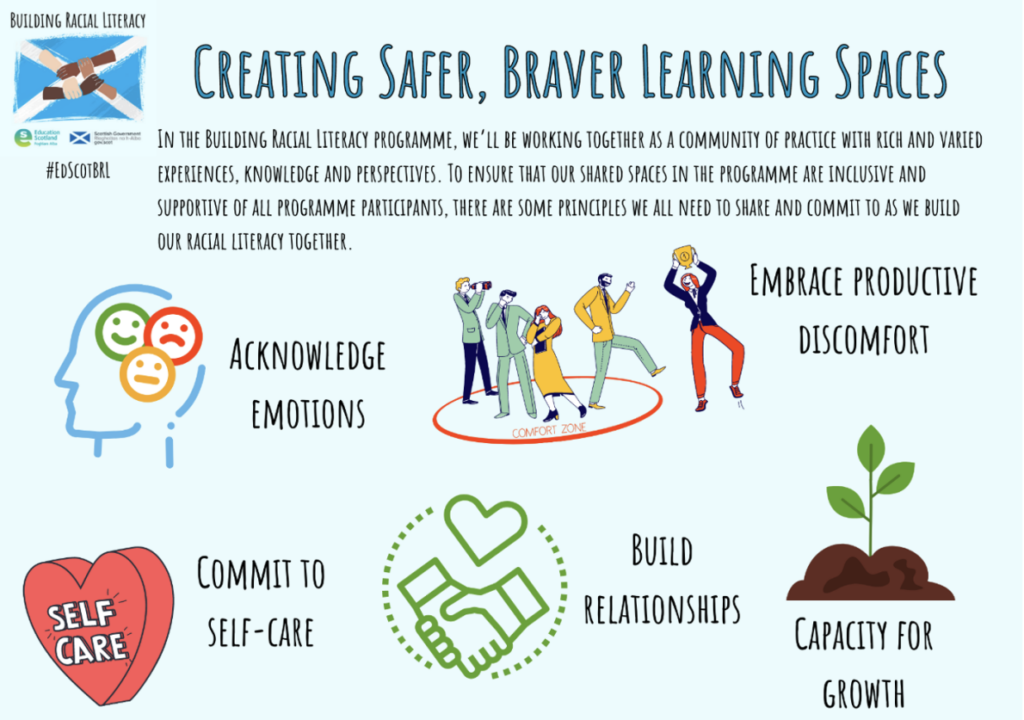

In the BRL induction, we also spend a lot of time unpacking our Safer, Braver Learning Principles: acknowledge emotions, embrace productive discomfort, commit to self-care, build relationships and capacity for growth.

SafeR because there is no way of guaranteeing that everyone will truly feel safe with the different power dynamics in a learning space. BraveR because we want to encourage everyone to step out of their comfort zone and be courageous in their learning. Our principles minimise disengagement and language paralysis when the course content becomes uncomfortable and even overwhelming. They promote healing and growth for the emotional, intellectual and professional challenges that come with anti-racist professional learning.

Finally, how do we know if BRL does what it set out to do – Build Racial Literacy?

There are many definitions out there for racial literacy, but we found France Winddance Twine’s definition to be the most comprehensive in helping us measure participants’ progress. France Winddance Twine defines racial literacy as “a form of anti-racist training” with:

- a recognition of racism as a contemporary, not just historical, problem

- a consideration of intersectionality

- understanding that racial identity is a social construct

- understanding the impact of whiteness

- the development of language to discuss race, racism and anti-racism

- the ability to decode race and racial micro-aggressions (Twine, 2010)

Looking at Cohort 1 participants’ pre-programme and post-programme surveys, there was an increase in every aspect of their racial literacy. The most significant increase had to do with participants’ confidence to decode racism and challenge it in a productive way through racial dialogue: “I feel confident dealing with a racist incident in my workplace.” Pre-programme, 65% of participants felt confident in that area and, after the programme, 100% felt confident in that area. Since then, our initial findings are similar for other cohorts but this is something we will continue to measure, to ensure BRL is achieving its intended outcomes, especially as the medium and longer-term impacts begin to emerge. With every new cohort, the diversity of our participants and of our team is a real strength. We have welcomed two Young Critical Friends of Colour who are Members of the Scottish Youth Parliament. By reviewing BRL and contributing to the course content, our Young Critical Friends are helping us centre more voices of young people. Diversity brings fresh perspectives on BRL; it helps us see things differently, it helps us grow as a programme and, in the words of Maya Angelou, it helps us know better and do better.

About the author

Mélina Valdelièvreis Lead Specialist (Race Equality) in the Professional Learning and Leadership Directorate, Education Scotland.

References

BRL poem, ‘Seeds of Antiracist Education’ by Tawona Sithole: https://professionallearning.education.gov.scot/media/2233/seeds-of-antiracist-education-poem.pdf

Valdelièvre, Mélina. (2019) Creating a Framework for Mutual and Production Communication about Race in Education: https://www.esu.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Scholars-report-2018-Melina-Valdelievre.pdf

Twine, France Winddance. (2010) A White Side of Black Britain: Interracial Intimacy and Racial Literacy.

The BRL Programme

You can learn more about BRL by watching our short, animated videos made by Hannah Moitt which tell the story of the programme so far:

To apply for the programme, more information can be found on this page: https://professionallearning.education.gov.scot/learn/programmes/building-racial-literacy/