In this wonderful blog post from Lottie Gaunt,we are treated to a rich example of how someone working in companion animal practice can explore opportunities in conservation medicine close to home, literally on our local rivers and the ecosystems they support. Lottie graduated from the MVetSci programme in 2024 and was awarded the Dick Vet Medal for her outstanding dissertation project, which you can read about below.

My journey into Conservation Medicine

Whilst I enjoy small animal veterinary work, I had an underlying restlessness that I wanted to be part of something ‘bigger’, that I wanted to explore other options that encompass not just animals, but the natural environment in which they live and the factors that influence this connection. However, I didn’t really have any idea how to redirect myself down this path; I had always been a vet, and didn’t really know any other career form. It was then that I discovered the Conservation Medicine programme at Edinburgh: I was drawn to the broad and interesting topic range. I was also at a point in my life where taking a break from work and pay wasn’t an option, so the practical fact that I could still work and make a living, whilst pursuing and developing this interest through intermittent study was very appealing.

I found I really loved the course, it was interesting, it was immersive, you had supportive and very knowledgeable lecturers and there was a range of teaching materials and projects from videos, to presentations, to word documents, which kept things vibrant and stimulating. During my studies, the biodiversity crisis and the impact that the destruction of wild natural habitats was having on both a national and global scale really affected me, both with the shock of the true extent of this disaster and a passion that this was something I wanted to investigate further.

This passion seeped into my dissertation year and I wanted to find a project that could have a practical tangible positive impact on the natural spaces and wildlife within my local area. With help from my supervisor, we identified a small section of wilderness in an otherwise very managed arable local landscape that appeared essential as a blue-green corridor for wildlife movement. I spent my dissertation year striving to find out as much about this area as possible, from its history to the wildlife it contains.

The aim was to ascertain if it could be improved for biodiversity, and whether a local protective status such as a Local Nature Reserve would be beneficial, to protect it in the future.

This project set me on an exciting and sometimes overwhelming journey, where I expanded my skill set considerably covering both online and onsite work, including site analysis, historical archive searches, interviews and subsequent qualitative analysis of those interviews. I also had the chance to work with Scottish Badgers and survey a badger sett on site, which was a fabulous experience. Elaine, who I worked with, was amazingly patient as I had never surveyed a sett before, and I loved being outside tracking footprints and examining the earth for evidence of badger hairs or soil disturbance.

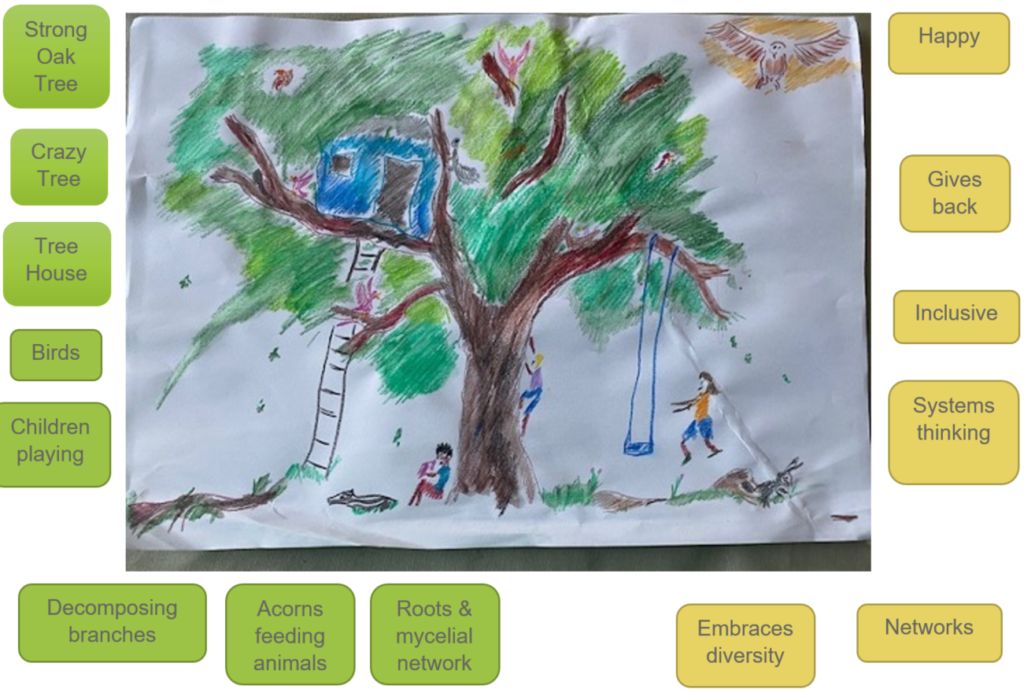

I also had the opportunity to join a workshop at the VetEd23, in July 2023, focussing on how Vet Schools can rise to the 30×30 Biodiversity Challenge. This ultimately lead to me becoming a small part of a discussion group on how veterinary schools can engage with the nature and biodiversity crisis which culminated in a subsequent publication-‘By Leaves We Live: Entanglements with the 30 x 30 Biodiversity Challenge on Veterinary Campuses’’, which was a privilege to be a part of. The work I put into my dissertation was awarded an MSc by distinction and was further recognised when I was presented with the William Dick Medal at my graduation ceremony; this came as both a shock and a very great honour.

The dissertation really highlighted for me the importance of the human, wildlife and nature connection, and how everything is interconnected. It revealed how important wild areas are, especially within otherwise highly cultivated environments, and how easily an area once known as an important wildlife hub can be forgotten, abandoned and disregarded. Ultimately, through my studies and research I came to appreciate the urgent need to preserve and protect the wilderness and wildlife we have, which are so critical to the future of our world. And whilst I am not sure which route I will take now the dissertation is finished, I am certain that I want to be involved in positive steps going forward as we battle the biodiversity crisis. I hope that, in the future, we, as humans, are more empathetic and understanding of whole system needs and have found the balance with nature that is so lacking today.

Figure 2: The author tending to a traumatised orphan rhino

Figure 2: The author tending to a traumatised orphan rhino

Guest post by Natalie Sampson.

Guest post by Natalie Sampson.