We’ve had an Accessible and Inclusive Learning Policy at Edinburgh since 2013. It was radical at the time, particularly in allowing students to audio record their teaching, but was looking rather dated even before the online pivot in 2020. In the context of an ongoing Curriculum Transformation project, how might we change it?

I’ve been looking at this policy since late 2019, on and off, supporting a review for a Senate committee. The original policy had and has a strong practical focus on mainstreaming, that is, taking measures made as adjustments for disabled students and mandating that these are universally applied. It does however seem to focus on didactic lecture delivery and contains technology references that are in danger of going out of date.

After ten years, the debates, technologies and pedagogies have moved on and the Accessible and Inclusive Learning Policy itself is clearly well behind the curve. Accessible and inclusive practice around the University can be exemplary in places but remains inconsistent, as does its impact on students, and the pandemic certainly drew attention to this. Nonetheless there are currently good opportunities to take advantage of the many developments over the last decade, particularly the increased awareness and indeed motivation of colleagues to address accessibility and inclusion in their teaching and their students’ assessment, and the impact of the Learn Foundations audit data in surfacing issues.

Report to Senate Education Committee, May 2023

To matter, to belong, to be included?

Meanings and interpretations change over time, and even though accessibility is wider than just disabled accessibility, to 2023 eyes the policy very much focuses on disabled students. “Accessibility and inclusion” to me should cover the other protected characteristics and ideally also address things such as caring responsibilities and economic differentiation, but there is a question about finding the most effective way to do this. A unified policy framework helps make sure nothing is missed and reflects the unified legal framework of the Equality Act 2010, but implementing change on this scale is often easier to do and communicate through staggered or parallel streams. Should this policy focus on disabled accessibility, and the other characteristics be picked up in other policies or additions to this one?

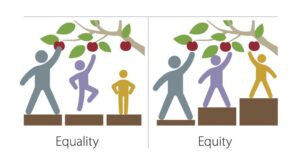

And again, meanings and interpretations change over time. University of Southampton’s Prof Pathik Pathak has argued that Equality, Diversity and Inclusion should be retired and replaced with Equity, Diversity and Belonging. Equity perhaps recognises better that the starting point is different, because the barriers to successful participation are different. There is also a paradigm change in the shift from thinking about inclusion, that perhaps implies a preexisting mainstream group framework into which we try to bring those with different characteristics, to thinking instead about how different members of a diverse group or organisation can all belong to the same extent, which implies a different, likely more co-created, framework.

And does everyone want to belong? It may ultimately prove to be sufficient, or it may be an intermediate step in changing culture, for every student to know they matter to the University – even those that perhaps don’t feel they can ever fully belong.

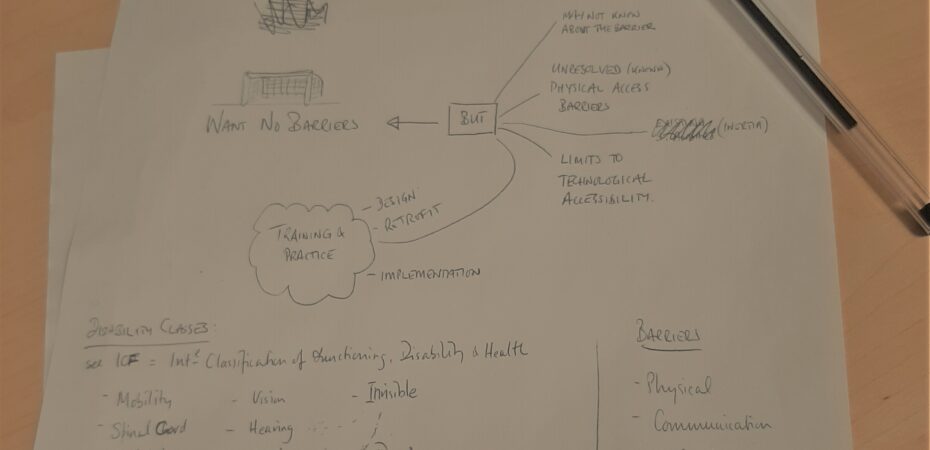

Mainstream universal design

It ought to go without saying (but for now we’ll say it loudly and repeatedly) that we should design out as many barriers as we can find. The challenge here is that there are so many barriers and of differing magnitude and complexity, and so we need to keep working to figure out the level of understanding, guidance and training required to develop a programme, course, lecture or field trip, and the level required for non-teaching roles.

Assessment of accessibility and equality within programme and course approval processes is a strong driver of change, but is reliant on something effective to measure against. We have some baseline accessibility standards within the current policy that can and should be expanded, but how do we manage the clear risk that the checklist becomes unmanagably long?

Audit

No, no yawning – I’m actually rather excited about auditing accessibility and inclusion as it’s something we’ve done and it seems to be another strong driver of change.

Learning, Teaching and Web Services colleagues have been assessing large samples of learning materials from the Learn virtual learning environment (VLE) for around five years now. Such systematic gathering of evidence across the whole institution is a lot of work, and Melissa Highton has given some figures that show the scale of the task just for the media side. We know the scope for this within the workload of academics or student support colleagues is limited, so how do we go about this?

student interns…have since gone on to be advocates for accessibility…

For the VLE, we train student interns to perform the audit assessments on selected courses from participating Schools, and then return the outcome to each School. We know that many of the interns have since gone on to be advocates for accessibility as they complete their programmes and move into their careers. The audits also help us as learning technology trainers decide where it might be best to focus digital accessibility training for colleagues. Interesting to think how we might take this sort of approach beyond digital materials on the VLE.

Student focus groups also provide evidence, albeit rather more anecdotally, but still valuable as individual cases show that we haven’t entirely succeeded yet.

Student voice

We want and need to listen to our students, and there are several sides to this. Firstly we might consider the extent to which students have clear, local points of contact to whom they can communicate about the barriers they are encountering, and how effective and fair the resolution or appeal procedures are.

Secondly the extent to which protected characteristic groups are and should be represented in the design and review of programmes and courses.

Thirdly whether we provide our prospective and current students with good information about equality impact, or how accessible and inclusive their programmes and courses are. There might be a parallel here with accessibility statements for websites and digital applications, where we are required by regulation to publish a report on how each website or app meets specific standards and how we plan to get it there if it doesn’t. Albeit in that case it’s easier since there are readily-available and internationally recognised WCAG standards.

Practical v aspirational

Another theme is how to balance the practical implementation of these measures when some of the goals of the policy may necessarily have to remain aspirational? The Equality Act is breach legislation, and so the standard is reasonable perfection. This is difficult for a pressured academy, as I’ve mentioned, and communicating and managing even the potential quick wins will need to be done carefully and astutely. In the short term, perhaps there are quick wins in small changes to practice that are already making more and more of our VLE documents fully accessible. The suggestion is that in the longer term we might need to look at:

- How we empower staff to understand accessibility and inclusion better and to design for them.

- How we assess accessibility and equality impact as part of approval.

- How we involve students from protected characteristic groups in design and review.

- How we measure where we are, against both legal requirements and against developing or world-leading practice.

Intention to tech well

It’s important to say, and I’ll finish with this, that the learning technology will likely only help our learning materials become more accessible and inclusive if it is intentionally designed and used to do so.

The design of an app or service needs to be intentionally accessible and inclusive, and you can probably think of examples where they haven’t entirely been baked in to the tech. The level of accessibility and inclusion in a given service likely reflects something of the level of training, the experience and the biases of the team that developed it.

And even if the nudges towards accessibility and inclusion are well-designed, the user may still thwart the system by (say) uploading a slideshow with unreadable contrast, or an image of a text document that cannot be read by a screen reader, or perhaps by phrasing something unhelpfully because of an unconscious bias.

Still, both the system and software design and the tools to assist users keep improving, and for example the University’s Learn users now have Blackboard Ally as well as Microsoft’s accessibility checkers to help spot issues and nudge us towards what they are programmed to promote as good practice. Learn’s new navigation system introduced last year is intended to be more accessible, as Tracey Madden discusses. We all as users, and also as policy influencers, can do our bit.

- Senate Education Committee is expected to discuss updating the Accessible and Inclusive Learning Policy at its meeting on 11 May 2023.

- Information Services provide guidance on Universal Design within its Learning Technology and Accessibility advice.

("Accessible Learning Notes" by Neil McCormick, The University of Edinburgh 2021 CC-BY)

(“Equity vs Equality” flickr photo by MN Pollution Control Agency https://flickr.com/photos/mpcaphotos/31655988501 shared under a Creative Commons (BY-NC) license)