Today there is almost constant talk in universities of excellence: excellence of institutions, of staff, and even of students. A quick search of the University of Edinburgh website yields teaching and research excellence (including the Research Excellence Framework), academic excellence, Exemplars of Excellence in Student Education, VLE Excellence, Tercentenary Awards for Excellence, the Centre for Service Excellence, the Service Excellence Programme, Celebrating Excellence, and a range of excellence scholarships. The language is relentless.

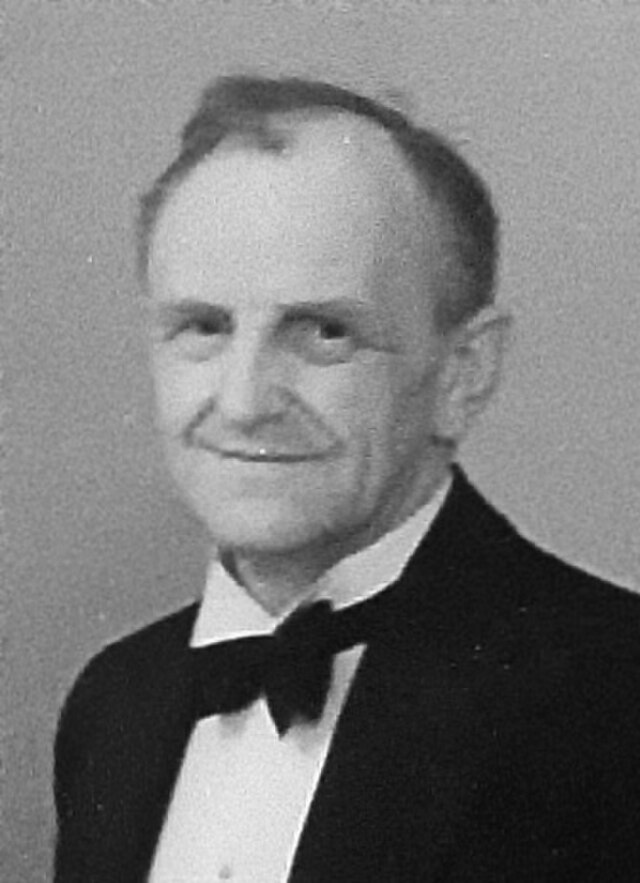

Set against this is the much less fashionable idea of good enough, a notion the psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott developed in relation to parenting. He introduced the idea of the good-enough mother in order to support what he called the ‘sound instincts of normal mothers’ (Winnicott, 1973, p. 173). This idea sits alongside his broader defence of ordinary parenting against the growing intrusion of professional expertise into family life, including his account of the ‘ordinary good mother’ (Winnicott, 1987, p. 123).

One of Winnicott’s central aims was to protect mothers from the pressure, often intensified by expert advice, to become perfect. Under such pressure, he argued, parents frequently became less good than they would otherwise have been. What mattered instead was being good enough. The good-enough mother does not aim at flawless care, but provides sufficiently reliable and responsive care while inevitably getting things wrong. Crucially, these ordinary failures are not merely tolerated but developmentally productive: they are what enable a child to develop resilience, independence, and a realistic relation to the world.

In a similar spirit, we might hold on to the idea of a good-enough university. Just as Winnicott sought to protect parents from professional overreach, a good-enough university would be protected from the shifting fashions of management and politics. The danger of making excellence the overriding institutional aim – excellence in everything, at all times – is that universities become increasingly responsive to external trends, policy agendas, and reputational pressures. Alongside this can come an emphasis on customer satisfaction and institutional alignment, often at the expense of difficult teaching, intellectual risk, and genuine educational challenge.

At this point, however, it is important to be clear: to argue for a good-enough university is not to argue against excellence as such, but to reject a particular institutionalised and externally imposed conception of excellence. The claim, then, is not that universities should aim at good-enough educational outcomes rather than excellence, but that they should be good enough as institutions in order to sustain the demanding forms of excellence internal to educational practices. As the philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre makes clear, excellence properly understood belongs not to institutions as brands, but to practices.

For MacIntyre, a practice is:

any coherent and complex form of socially established cooperative human activity through which goods internal to that form of activity are realized in the course of trying to achieve those standards of excellence which are appropriate to, and partially definitive of, that form of activity (MacIntyre, 1985, p. 187).

Chess, for example, is a practice: participants learn and play the game while recognising internal goods such as analytic skill, strategic imagination, and competitive intensity (MacIntyre, 1985, p. 188). Other examples include football, architecture, farming, music, painting, and the enquiries of physics, chemistry, biology, and history. Excellence in these practices is internal, achieved through the mastery of skills and sustained engagement with the practice itself – very different from the externally imposed, benchmarked excellence often rewarded in universities.

In his later work, MacIntyre sharpens this contrast by distinguishing between the goods of excellence, realised by agents through participation in practices and traditions of enquiry, and the goods of effectiveness, which concern success, influence, and competitive advantage (MacIntyre, 1988). Here the emphasis is less on institutions as such than on the orientation of agents and forms of practical reasoning: whether one’s activity is ordered toward standards internal to a practice, or toward externally rewarded success. The danger for universities, as institutions shaped by the modern social order MacIntyre describes, is that they increasingly reward and reproduce the latter orientation, even while the former remains the proper aim of education.

A good-enough university, then, is not one that abandons excellence, but one that creates the conditions in which the excellences internal to disciplinary practices can be pursued. Its primary task is educational: to initiate students into particular disciplines and, in doing so, to induct them into the standards, goods, and virtues that those practices embody. At the same time, it should help students to understand how different disciplines contribute to a broader and more reflective understanding of the human condition.

Such a university would provide a decent education grounded in the research of its staff, and accept that teaching and learning are necessarily imperfect, demanding, and sometimes uncomfortable. It would also recognise that universities have different missions and strengths, and that not every institution needs to be excellent in every respect. At the same time, it would remain attentive to the broader purposes of higher education. In losing sight of this distinction – between institutional performance and practical excellence – the university risks losing something more fundamental: its capacity to remain a good-enough place for thinking, teaching, and learning.

References

MacIntyre, A. (1985). After Virtue: A Study in Moral Theory (2nd ed.). London: Duckworth.

MacIntyre, A. (1988). Whose Justice? Which Rationality? Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press.

Winnicott, D. W. (1973). The Child, the Family and the Outside World. London: Penguin.

Winnicott, D. W. (1987). Home Is Where We Start From: Essays by a Psychoanalyst. London: Pelican Books.

(Donald Woods Winnicot. Cropped from A dinner to celebrate Melanie Klein's 70th birthday, at Kettner's, London. W.1, 1952.)