Week 3 Class Assignment: Art Assignments & Learning Theories

Before we jump into learning theories, consider what you did when taking part in Build-a-Basho, Make Gold and Artists’ Toolkits at ESW.

All were open toolkits that took the form of an art assignment; a set of simple instructions that you followed.

Collections of Art Assignments:

Draw it with your Eyes Closed

The art assignment is an approach that is widely practised in art education, specifically in its early foundational stages.

An art assignment is a teaching technique akin to an artists’ toolkit. While art assignment can be an artists’ toolkit, an art assignment tends not to include a comprehensive set of materials.

The art assignment largely leaves key questions of figuring out how and what to make to the participant. Moreover, where a toolkit suggests a “goal” – that is something that will be learned, or accomplished – an art assignment may not have a “goal” (either impliticitly or explicitly).

The book Draw it with your Eyes Closed (link) delves into the art of the art assignment, engaging artists to discuss art assignments that they were set and that they might set themselves.

Not all contributors are fans of the assignment format – but, on the whole, the art assignment is something they have all experienced as part of their art education.

You can read some of the assignments here:

https://drawitwithyoureyesclosed.com/ (link)

Here is a particularly meta art assignment from Draw it with your Eyes Closed to start with (you can follow this if you want, but reading it will suffice):

JACKIE BROOKNER–RULES ASSIGNMENT

Of course we know artists have a kind of congenital allergy to rules, especially somebody else’s rules. We like to make our own rules. Very freeing, right? Well, that’s not the whole story. Let’s take a look at the rules you are following, especially ones living below the threshold of consciousness. Make a list of these rules, right now. Which of them that you think are your rules, are really rules you’ve inherited, been taught, learned are the cool rules? Are they serving you, or trapping you?

WEEK 1

As you work throughout this next week, try to hear the rules whispering to you. Keep a running list, and add to it every time you hear another one. Don’t read any further until you’ve done #1.

WEEK 2

OK, you cheated, because it was my rule. Now, what kind of rules did you come up with? Are they the easy formal ones about choices of materials, how long or short the piece should be, or what to wear? Try again, and listen for the harder ones: the conceptual limits you put on your work, the kind of work you let yourself do, or not do. Are there whole parts of your being you put in a separate compartment and don’t even consider bringing into your work? Whole enthusiasms you haven’t let yourself imagine as part of your work? Embarrassments, naiveties, intelligences you leave out?

WEEK 3

Now, this week do whatever you have to do to break your own rules. The hardest ones first.

https://drawitwithyoureyesclosed.com/post/67290458311/jackie-brooknerrules-assignment

The Art Assignment – Sarah Ulrist Green

If you haven’t had an art education, where else might you encounter art assignments?

Increasingly, art assignments can be found online:

For example, The Art Assignment is an OER website and PBS channel, hosted by curator Sarah Ulrist Green, that hosts assignments written and presented by different artists:

https://www.theartassignment.com/assignments-landing (link)

https://www.pbs.org/show/art-assignment/ (link)

https://www.youtube.com/user/theartassignment (link)

Sarah Green’s show is primarily a way of exploring art history as practicum: working directly with materials and making processes that artists have engaged with in different historical periods. This has long been an important project within art history as a discipline, especially within the curatorial sector which has a particular investment in haptic, or ‘hands-on’) research methods (because curators tend to work directly with objects).

Green’s Public Broadcasting Service approach is also her way of fulfilling the public mission of the museum as an educational institution.

Green also enlists contemporary artists to establish their own assignments. This helps her audience to engage with emerging art on material and haptic terms. Herein, Green is initiating an experiential learning process.

The assignments in Green’s PBS show are often simple to follow and require little expertise, skill or specialist equipment. Each assignment engages the participant in the weltanschauung of the artist that has set the assignment. Taking part in each assignment can offer a microcosmic insight into the artists’ macro-view of art and their environment.

Learning to Love you More – Harrell Fletcher & Miranda July

The Art Assignment follows a model established by the artists Harrell Fletcher and Miranda July in the earlier days of the web:

http://learningtoloveyoumore.com/

https://www.dailymotion.com/video/x2p4q0u

The call-response format of Learning to Love you More (2002–2009) is, in essence, the challenge of the art assignment. The assignment establishes a set of simple parameters that set out a field within which to play. While designing the parameters in the form of the assignment is an art in itself, it’s the mere presence of the enabling constraints that matter.

Art Assign Bot – twitter @artassignbot

For example, the bot https://twitter.com/artassignbot randomly generates art assignments that have both commands and constraints. While some might prove impossible to follow, most of @artassignbot’s tweets can be completed (e.g. Build a flipbook about burglaries, due on Wed, Mar 14.)

The considered learning design we’d expect from Green’s The Learning Assignment or Learning to Love you More isn’t present since the bot is an algorithm rather than a more sophisticated AI. Nevertheless, if more than one participant were to follow the prompts of @artassignbot they could establish a paragogics by posting and comparing their responses.

Enabling Constraints

The emphasis on establishing enabling constraints dates back to the late 1950s when art education started to be influenced by systems theory. In England, the dominant art school models at the end of the 1950s were the ‘South Kensington System’ derived from the Royal College of Art, London and the ‘General Design’ method derived from the Bauhaus, Dessau. There are two particularly (infamous) art programmes in England during that period, both of which made extensive use of art assignments:

Here is Ascott discussing Groundcourse at Shift/Work, Edinburgh Sculpture Workshop.

Groundcourse (Roy Ascott, Ealing Art School / Ipswich Art School, 1961-Present)

As you will see from this video, the team-taught Groundcourse was largely based on second order Cybernetics.

See also:

Sloan, Kate Art, Cybernetics, and Pedagogy in Post-War Britain: Roy Ascott’s Groundcourse

Emily Pethick, Degree Zero https://www.frieze.com/article/degree-zero

Sculpture Course ‘A’ (St. Martin’s School of Art, 1969)

Since it was devised by a team, the accounts of what Sculpture Course A did differ dramatically:

Please read:

Heston Westley’s “The Year of the Locked Room: St. Martin’s School of Art” in TATE Papers https://www.tate.org.uk/tate-etc/issue-9-spring-2007/year-locked-room (link)

See also:

The Locked Room, Four Years that Shook Art Education, 1969-1973

Post-studio (John Baldessari 1970, CalArts, California, USA)

In North America, we can see a similar turn to the assignment in seminal programmes which began at the turn of the 1970s:

https://eastofborneo.org/articles/a-situation-where-art-might-happen-john-baldessari-on-calarts/

See also:

You can read some of John Baldessari’s assignments here:

https://painterskeys.com/fourteen-assignments-john-baldessari/

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gO49s8WlUis&feature=youtu.be

John Baldessari I Will Not Make Any More Boring Art Art assignment for NSCAD students, https://smarthistory.org/john-baldessari-i-will-not-make-any-more-boring-art/ 1971, 31:17 min, b&w, sound

Richard Hertz on the CalArts Mafia (graduates of Post Studio Program). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AHL_dA_K9Ig (link)

Feminist Art Program (Rita Yokoi, Miriam Schapiro, et al 1970 Frenso State Universit; Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro 1971-1981 CalArts, California, USA)

Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro ‘Womanhouse’ Catalogue cover, 1972 CalArts, California, USA

Further reading:

Verena Kittel – Let the Subaltern Speak: The Archive of the Feminist Art Program describes how the FAP used used assignments “aimed at helping its students to develop self-assurance, gain strength, be ambitious, and pursue and achieve their own goals.”

See also:

Suzanne Lacy on the Feminist Art Program at Frenso State and CalArts

NSCAD (Garry Neill Kennedy, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada)

Page from Kennedy, G.N., 2012. The last art college : Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, 1968-1978, Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Post-studio at CalArts was closely intertwined with NSCAD: – Nova Scotia College of Art & Design

4-D Sculpture (Paul Thek, Cooper Union, NYC, 1978-1981)

Paul Thek with his installation The Tomb: Death of a Hippie (1967)

Paul Thek is another good example of an artist-educator who made extensive use of assignments:

📎 Chris Krauss on Thek’s Teaching Notes

https://cooper.edu/about/news/paul-thek-modern-institute

If you investigate art assignments a little more online, you will find many examples.

For now, we will turn to learning theory. We will return to this at the end of this learning module.

What are Learning Theories and how might you start to navigate them?

(Three Learning Theories)

(Three) Learning Theories

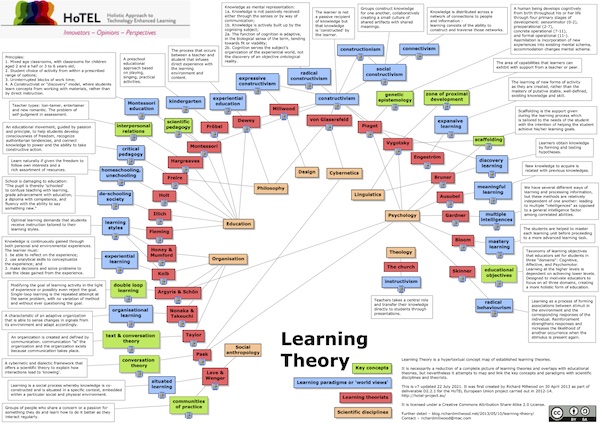

HoTEL Learning Theory Map by Richard Millwood http://blog.richardmillwood.net/2013/05/10/learning-theory

Please Download: https://blog.richardmillwood.net/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/Learning-Theory.pdf

Interactive Version of Richard Millwood’s HoTEL Learning Theory Map http://cmapspublic3.ihmc.us/rid=1LNV3H2J9-HWSVMQ-13LH/Learning Theory.cmap

As you can see from the HoTEL Learning Theory Map, there are many learning theories that we could introduce here and study! (If you click on the interactive link above, you can find out more….) We just don’t have the time to take all of this in, so I will run through just three learning theories. I’ve chosen them because they are either practiced already in art educational (albeit opaquely) or because they have particular relevance to art education in the 21st century.

I will stick with the three key examples referenced above. Remember that these are just examples, there are many many more examples of assignment-based art education that we could draw on!

See also:

- https://www.mybrainisopen.net/learning-theories-and-learning-design/

- Donald Clark’s 100 learning theorists

- https://www.learning-theories.com/

We will try to learn a little about learning theory by applying it to the model of the art assignment as a typical example of a teaching method used in art education.

Learning Theory Example #1

SOCIAL CONSTRUCTIVISM

In learning theory, the focus on how knowledge is constructed through forms of social interaction is called social constructivism. This approach is very common in Artistic Learning. It is mainly attributed to the Soviet psychologist Lev Vygotsky (1896-1934) and further back to the ‘first wave’ behavioral constructivism of Jean Piaget (1896–1980).

In Mind in Society: The development of Higher Psychological Processes (1925-35) – Vygotsky rejected Piaget’s contention that learning can be separated from its social context. Vygotsky, rather, argued that learning was the active collaborative process wherein students engage with a community of learners.

Social Constructivism and Artistic Learning

Social Constructivism is omnipresent in Artistic Learning in ways that are often ‘unconscious’. For example, the commonly held assumption that art students should be gradually relieved of structure (in the form of mentoring or art assignments) and encouraged to pursue their own learning paths is one rooted in Vygotsky’s concept of ‘scaffolding’. The scaffolding support is gradually removed as learning is internalised, leaving students to stand on their own.

Social Constructivists see learning as experiential: students learn by doing. We bring prior experience to bear on new experiences and attempt to reconcile the two. In this, Social Constructivists draw a great deal of sustenance from the work of the American philosopher John Dewey (1859-1952), particularly his book Experience and Education (1938). Dewey’s experiential learning theories have had profound influence on art education in the USA, and his emphasis on school as an institution for social reform spearheads a great deal of North American Social Practice.

See: Helguera, Pablo (2012). Education for Socially Engaged Art. New York: Jorge Pinto Books

From a Social Constructivist perspective, art-learning projects such as Fletcher and July’s Learning to Love You More, The Art Assignment and @artassignbot would be seen as forms of scaffolding that encourage very particular forms of ‘subjectivisation’. Such projects scaffold the process of becoming-artist in particular ways that we can trace and subject to deconstructive scrutiny. Learning to Love You More is also overtly experiential; we are frequently asked to draw upon our previous experience in order to complete its assignments.

Social Constructivists constantly seek to investigate and challenge how we construct (scaffold) learning through our social interactions and our social experiences. Thus, the ways we design learning by devising and supporting forms of social interaction are absolutely pivotal in how we develop personhood (the ‘self’). While this scaffolding can be carefully designed/structured, the studio itself is often presented as the crucible wherein social interaction imparts artistic knowledge. The studio (or at least so it is often claimed) is a panacea for experiential learning.

Note that the emphasis in this model of Artistic Learning is on the support given to individual learners and upon their development as individuals. You can see this rhetoric everywhere in art education, with its emphasis on finding your own disctinctive ‘vision’ and becoming creatively ‘whole’ and its relative lack of interest in collective practice or collective research. It is also a view echoed more widely in education now, which equally focuses on personal development and learner-centred approaches.

Learning Theory Example #2

CRITICAL PEDAGOGY

In learning theory, critical pedagogy can be seen to shift the focus on how knowledge is constructed through forms of social interaction towards thinking about how knowledge is constructed by society as a whole. More broadly, within the social sciences, this is called social constructionism.

See: Peter L. Berger and Thomas Luckman, The Social Construction of Reality, 1966

Where Constructivists, such Piaget and Vygotsky, hold that individuals construct knowledge within their own minds (‘mental models’), social constructionists see knowledge as constructed by groups, via social discourse.

In the late 1960s, Critical Pedagogues such as Paulo Freire and Henry Giroux sought to surface and deconstruct the buried politics of educational institutions (the ‘hidden curriculum’) in order that they might become proponents of radical social change.

Critical Pedagogy and Artistic Learning

Pedagogy of the Oppressed (Friere 1968)

The Social Constructionist perspective – that culture is made not given – is a dominant paradigm within contemporary art. Since culture is made, it can be unmade and reshaped in different forms. We can see this perspective activated in innumerable (postmodern) artworks that take, as their starting point, the view that culture is socially constructs rather than represents ‘reality’. This stands in stark contrast to the essentialising views that are still common vis a vis art education: e.g. that talent is ‘innate’, that great artists are born great artists, that art cannot be taught. While essentialising views still exist in art education, they are widely regarded as belonging with the domain of the ‘amateur’ artist.

Critical Pedagogy is a popular topic within the educational turn in art practice and curating. Friere’s ideas in particular have witnessed a renaissance in the 21st century. A Pedagogy of the Oppressed (Friere 1968) is less visible within institutional art education, much of which has not been reformed in any significant way since the late ’60s. Where it did surface, Critical Pedagogy has

involved faculty and students attempting to radically reform their institution.

For example, the student occupation of Hornsey

Students and staff of Hornsey College of Art (1969). The Hornsey Affair. Penguin Education. ISBN 9780140800968

Art School, North London in May-July 1968 was one occasion when Freirean Critical Pedagogy was applied as students took over the administration of their art school. While the occupation of Hornsey ended the educational experiment, its reverberations can still be felt. See: Tickner, L., 2008. Hornsey 1968 : the art school revolution, London: Frances Lincoln. This project http://radical-pedagogies.com/ led by Beatriz Colomina, maps out radical pedagogy in Architectural education in the latter half of the 20th century.

The Feminist Art Program, equally, actively deconstructed patriarchal art education and replaced it with a radically new feminist approach, encouraging critical thinking that brought about social change. An early assignment that foregrounded critical pedagogic dissent involved faculty and students of the Fresno Feminist Art Program renovating their own off-campus studio.

More broadly, on a practical level, there are many art programmes that actively engage with the theory that knowledge is socially constructed broadly within society as a whole. For example, some faculty and students on the Feminist Art Program focused on investigating gender as a social construction while other feminists opposed this proposition. The debate regarding social constructionism continues within, and between, feminism, queer and trans politics.

Learning Theory Example #3

CONNECTIVISM

In learning theory, the focus on building P2P networks is called connectivism. This approach is attributed to George Siemens and Stephen Downes. In this video George Siemens explains what Connectivism is from his perspective:

If you want to dig a bit deeper still, reading Siemens’ Connectivism: A Learning Theory for the Digital Age (2005)

For now, let’s highlight three of Siemen’s’ Principles of Connectivism from this paper:

Siemens_2005_Connectivism_A_learning_theory_for_the_digital_age.pdf (link)

- Learning and knowledge rests in diversity of opinions.

- Learning is a process of connecting specialized nodes or information sources.

- Learning may reside in non-human appliances.

- Capacity to know more is more critical than what is currently known

- Nurturing and maintaining connections is needed to facilitate continual learning.

- Ability to see connections between fields, ideas, and concepts is a core skill.

- Currency (accurate, up-to-date knowledge) is the intent of all connectivist learning activities.

- Decision-making is itself a learning process.

- Choosing what to learn and the meaning of incoming information is seen through the lens of a shifting reality.

- While there is a right answer now, it may be wrong tomorrow due to alterations in the information climate affecting the decision.

‘Connections’ vs. ‘Content’

Siemens & Downes stress the importance of connections over the content that they connect. In this, they follow systems theory in focusing on ‘ties’ (connections) over ‘nodes’ (the elements that ties connect together.)

Is Connectivism only Digital Learning?

Connectivists focus on how learning is advanced through forging new connections between existing bodies of knowledge. These connections are always being made but are accelerated by the advent of online (digital) learning in the form of what Siemens calls MOOCs (Massive Open Online Courses, coined by Dave Cormier, 2008). As such, Connectivism is often read as a theory of online learning, accessible only to learners who can easily access the web.

Connectivism and Artistic Learning

Here’s quick search you can conduct to see what’s available for art and designers:

https://www.my-mooc.com/en/categorie/visual-arts has just 43 MOOCs on art and design.

Are any of them able to support practice?

On a practical level, you may find that there are very few MOOCs that support art or design learning.

In contrast, there are many MOOCs on art and design histories.

This might tell us that, as yet, MOOCs are not where we will find connectivist ideas in art education. We need to look elsewhere, namely towards the educational turn in curating and artistic practice. For example, let’s return to example drawn from Greene’s The Art Assignment:

https://www.theartassignment.com/assignments//customize-it

Brian McCutcheon’s assignment is hosted by The Art Assignment, which acts as its Learning Management System (LMS). Note that submissions are to any social media platform we choose, so long as we adopt the hashtag of #theartassignment. The # thus becomes a ‘distributed’ LMS that fosters connections.

From a Connectivist perspective, art-learning projects such as Learning to Love You More, The Art Assignment and @artassignbot could be seen as Learning Management Systems (LMS) that share an ability to connect large numbers of participants (‘massive’) through establishing common learning endeavors.

For example, by encouraging Learning to Love You More participants to post their assignments, the projects’ Learning Management System (the website) was able to aggregate contributions and enable participants to compare and contrast their learning. The art assignments on the LMS aren’t what’s important, nor are the completed assignments submitted to it. What matters that the project encourages participants start to engage with each other.

As Sarah Green might put it, the art assignment is the MacGuffin that ‘sparks creation’. While an outcomes-based learning approach might want to focus on how Learning to Love You More was the catalyst for numerous submissions/works of art, the Connectivist would say that what actually matters is that connecting with other learners via the project. @artassignbot generates connections capable of sparking off learning.

Learning without Teachers?

Downes is clear about the broader agenda for Connectivism and its role in the Open Educational movement:

In terms of the three examples given here, what ‘expertise’ is being accessed when people participate in art assignments that do not have an obvious or intentional (human) author (e.g. @artassignbot).

Siemen’s Principles state that Learning may reside in non-human appliances. How is this so, how it possible to learn in without experts/teachers?

Connectivism’s teacherless education has some parallels with Friere’s teacher-student continuum – a flattening of the master>apprentice hierarchy prevalent within what Friere called the ‘banking view’ of education. Where Critical Pedagogy’s teacher-student continuum questions and challenges domination, Connectivism moves to eliminate teachers altogether so that everyone is a learner. Would this challenge domination, or would it lead to new forms of information domination? Might applying Critical Pedagogy to Connectivism reveal how it is ideological, dominated by a technocratic worldview?

Week 3 Class Assignment

Please turn-in the Class Assignment to Learn by Tuesday 10th October, 9:00am.

Instructions on how to complete this assignment are all in Learn.

Please check Learn for details and ensure that you turn-in your work there.