Last summer, record temperatures within the Arctic Circle at locations as widely spread as Canada, Russia and Norway, sparking concerns about the future of the tundra biome. Occasional record peak temperatures can be harmful to life here, but they constitute only one part of the story. It will be the long-term, persistent increase in temperature that drives changes in ecosystem structure and productivity, and such changes are occurring: in spring 2019, High Arctic Svalbard reached 100 consecutive months with above normal temperatures. The Arctic is in the grips of an ever-growing climate crisis.

Why should we be concerned? Colder regions are considerably more responsive to increased temperatures compared with warmer regions. The tundra, in particular, can serve as an early warning system in understanding ecosystem responses to climate change. As the Arctic warms, the vegetation responds and widespread greening due to invasive shrub encroachment is reported. This, not only involves a diversity loss but also increases soil microbial activity, mobilising gigatonnes of carbon previously stored in frozen soils, a feedback loop with unknown consequences.

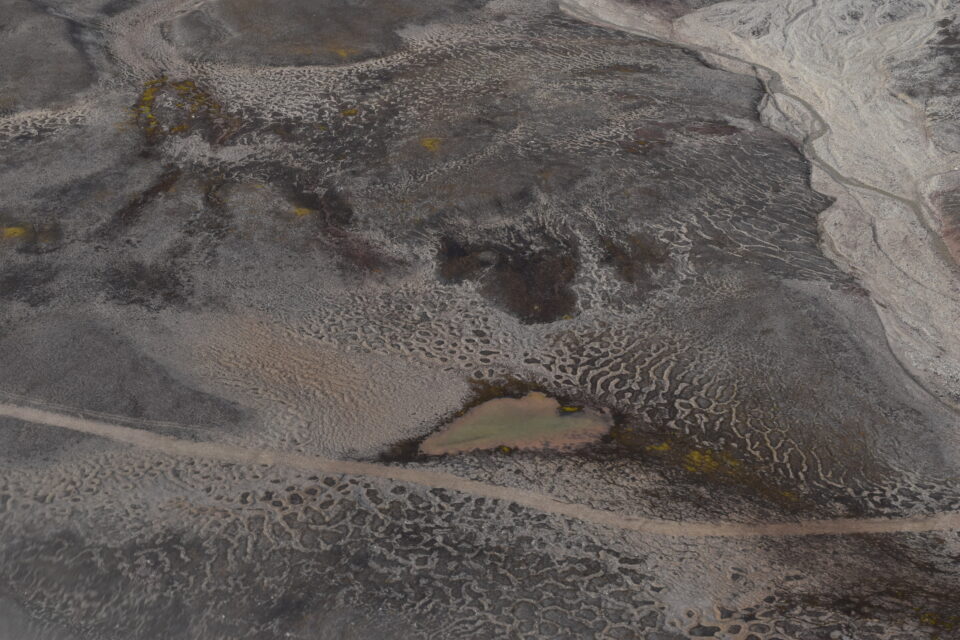

What is at stake? High Arctic vegetation is distinctive. Any organism able to survive the harsh conditions here must have highly specialised life traits. Consequently, organisms that are desiccation-tolerant and can equilibrate their water content with the surrounding air, such as lichens, mosses, and algae – which collectively form biological soil crusts (BSCs) – are dominant. However, whereas BSC communities have been well described, we know little about how increasing temperatures, both in the form of short-lived heatwaves and in the form of persistently warmer temperatures, will affect their growth and productivity.