MetMo Cubes for Korman: better ways around the composition as identity thesis

In this post I have have selected one of the points I made for an undergraduate epistemology and metaphysics essay on the existence of ordinary objects. In my essay I defended Daniel Z. Korman’s philosophy of ordinary objects by (I hope) improving on his refutation of the overdetermination argument against the existence of ordinary objects. Here I have chosen to write solely about Korman’s refutation of the ‘composition as identity thesis’ but would be happy to cover a more broad copy of my points on overdetermination in a future work. I would also like to recommend that anyone interested read Korman’s (2015) Objects: Nothing out of the Ordinary – it is probably the most entertaining and clear philosophy book I have had the pleasure of reading at university.

As always please feel free to comment any thoughts about this topic or any suggestions!

MetMo Cubes for Korman: better ways around the composition as identity thesis

Korman (2015) sets out to defend the view that our common sense tells us what objects exist or don’t exist. This view posits that most of the time we are intuatively correct about what objects exist, and situations when we mistakenly think some objects exist but they in fact do not can be easily explained by unproblematic external lapses in our judgement – ie optical illusions or cognitive biases. In simple form this view claims, we know that there are such things as chairs, xylophones and pencils but have rightfully very little idea of what in the world a zxlgogiloprom is because zxlgogiloproms don’t exist. Throughout his book Korman refutes 9 classical arguments against the common sense view more or less successfully – each time undermining the premises or inferences supporting each argument. Of these I have always been most interested in the overdetermination argument. Though many versions of the argument exist and have slightly different premises such as Vicente (2004) and Merricks (2001), the main jist is that: if every object is a composition of atomic simples and that these compositions of atomic simples can explain every property of that object in the world, then why should we believe that we live in a world there are such things as ordinary objects and not just a world consisting of differing compositions of atomic simples?

Defenders of this view take that having both ordinary objects and their compositions both existing simultaneously is an overdetermining cause of an “object’s” properties and – by Occam’s razor – one of the two must not exist [1]. For most it is then preferable to keep the existence of atomic simples and to drop that of ordinary objects. To make this argument more clear Korman uses the analogy of a baseball: “1. Every event caused by a baseball is caused by atoms arranged baseballwise. 2. No event caused by atoms arranged baseballwise is caused by a baseball. 3. So, no events are caused by baseballs. 4. If no events are caused by baseballs, then baseballs do not exist [Occam’s razor]. 5. So, baseballs do not exist.”(Korman 2015 pp.191). There seems to Korman many ways out of this argument and he goes down these routes wholeheartedly. However, I am much more interested in one route that Korman believes is not so useful to defend ordinary objects. This route he calls the ‘Composition as Identity Thesis’ (CAI). This states that every ordinary object is just a sobriquet that refers to a particular arrangement of atomic simples in the world. That “if O is composed of o1…on, then O is identical to o1…on [taken collectively]” (Korman 2015 pp. 15). For example, a ‘chair’ refers to atoms arranged chair-wise, a ‘hydrogen atom’ is identical to the arrangement of fundamental particles constituting a proton and an electron, and a ‘Liam McLaughlin’ is just another name for atomic simples arranged Liam McLaughlin-wise.

Though this would raise a plethora of issues such as permanency of a Liam McLaughlin overtime (as I gain and lose atoms) and the applicability of using ‘chair’ to collectively describe multiple chairs, the CAI thesis is at first very attractive. This is because it allows us to reduce ordinary objects and their atomic composition to one and the same entity, thus meaning that the causes of an object’s properties are not overdetermined as there is only one cause [2]. Indeed, this would also allow us to show Korman’s rendition of the overdetermination argument’s second premise, “2. No event caused by atoms arranged baseballwise is caused by a baseball” (Korman 2015 pp.8) to be trivially false. Since we could re-write 2. as ‘no event caused by a baseball is caused by a baseball’ or ‘no event caused by atoms arranged baseballwise is cased by atoms arranged baseballwise’ [3]. However, Korman argues that this CAI based refutation is not as helpful a solution as it first appears.

Here Korman relies on the Leibniz law of identity: that identical entities must have identical properties. Or more formally ∀x∀y(F)((x=y)→(F(x)≡F(y)). He argues that ordinary objects and their atomic arrangement cannot be identical (by Leibniz law) as their permanence conditions differ. He states that, if a tree’s leaves suddenly cease to exist, the remaining object would still be a tree despite the previous arrangement of parts no longer existing (Korman 2015 pp. 16). Therefore, though the arrangement of atomic simples has changed, the tree itself continues to exist. Hence, the tree and its composition differ in at least one property (permanence) and therefore cannot be an identical entity – refuting the CAI thesis.

I agree with Korman’s assessment that the CAI thesis is not cogent. However, I find his example not entirely convincing, as we could claim the leaves never composed the tree, they were merely another object on the tree, and are therefore irrelevant to being arranged tree wise. Thus, Korman would have begged the question in assuming that leaves were originally part of the tree – making the example redundant [4]. These ‘question begging’ responses can also be used against concerns that Liam McLaughlin’s atomic composition changes over time, by claiming that the atomic simples that were relevant to be being arranged as Liam McLaughlin-wise never changed or were replaced identically such that they remained being arranged Liam McLaughlin-wise (a Liam shaped ship of Theseus?). Even the earlier example where we have multiple chairs with different forms that are all equally chairs, can be explained away by there being some arrangement of atomic simples that perfectly explains what it is to be a chair and that this arrangement is common to all chairs despite their idiosyncratic variations.

Claiming that only part of the ‘chair object’ is relevant to be arranged chair-wise would necessitate we abandon the first rendition of the CAI thesis, however, there is still a salvageable CAI thesis within. Under this salvaged CAI it is necessary to claim that some atomic parts that we erroneously believe composed our ordinary objects are either their own object (like leaves on a tree) or are irrelevant to any composition/properties of the object (like variations between difference chairs). We could do this quite simply by claiming that identity is composition, but that we often erroneously refer to a whole bunch of atomic simples when we really mean only the relevant atomic simples to be a chair [5]. Though I entertain these thoughts I think the illustration above shows how absurd such a position would be – requiring that through solely atomic composition we explain how ‘all chairs are chairs, but some are more chairy than others’. Yet, these ‘question begging’ responses still do have some power in showing that the Korman’s tree example is not a cut and dry refutation of the CAI thesis. Indeed, more generally subtractive examples against the CAI thesis don’t really work because from the moment we remove one part of the atomic composition, our example becomes vulnerable to the ‘question begging’ response. Since each time the part subtracted from the object whole composition, we may say, must have been assumed to be relevant to the identity of the object for the example to have any weight in disproving CAI thesis. However, I think Korman’s refutation of the CAI can be saved by more compelling additive examples. These are situations in which an object ceases to exist despite it’s atomic composition remaining unchanged – sidestepping the ‘question begging’ response.

Allow me to introduce MetMo cubes!

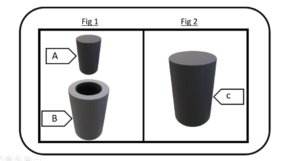

These are steel blocks made using Wire Electrical Discharge machining that are cut so precisely that they can be fit together without causing a single visible joint (see end for video). They seem almost impossible but as shown in the diagram they can – take my word for it – fit together without you knowing that a gap ever existed. Despite just being quite cool these blocks are also very useful as from these I believe it is possible to create an additive example against the CAI thesis.

Consider the steel chunks A and B that are cut so precisely that A could fit into B without any visible joint – creating C. Despite there being no change in A’s material composition, since it is not chemically bonded to B, an ordinary observer of Fig 2 cannot discern that A had ever existed. It is as if A never existed separate from B despite neither composition having being changed. Since Korman believes we tell which ordinary objects exist from our common sense, an observer’s inability to perceive object A’s existence separately from object C is tantamount to A ceasing to exist (Korman 2015 pp.1). Thus, the resulting difference in permanence conditions refutes the CAI thesis through the same Leibniz law mechanism as Korman’s subtractive example.

Of course these types examples too are questionable. Yet I think we might still say that a scenario could be constructed where beyond external lapses in our judgment we mistake an assembly of MetMo parts as a whole. Perhaps objectors can then instead appeal to object permanence that babies tend to learn at 9 months old or that instead we must relativise the existence of an object to a particular place in space/time/space-time as way out of the example. However, I think that after a certain point there does not seem a way to refute additive examples without appearing overly contrarian – but I leave you to judge.

I hope that you have found this brief dive into MetMo cubes and metaphysics at least superficially interesting. I atleast have been able to use it to introduce a pretty cool gizmo that I hope shows an eye-opening point. To end this off I can’t recommend Korman’s objects: nothing out of the ordinary highly enough and I hope you take a look. Luckily a copy of his book is only £25 much less than the exorbitant £250+ of a high enough quality MetMo cube to fool an observer (as above). I myself, however, will be reading his book online/at a library, but if just 10 readers buy his book (neglecting publisher fees) that will be enough to get … a MetMo Cube for Korman!

Liam McLaughlin – 3rd year PPE student at Edinburgh University

[1] Occam’s razor the main jist: “Most philosophers believe that, other things being equal simpler theories are better” (Stanford Encylopedia of Philosophy – Simplicity https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/simplicity/). Another good look at occam’s razor for the more video centric: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M5WDdvkFaDg.

[2] Thus, not meeting Korman’s 5th condition for overdetermination; that overdetermining causes must be distinct from each other.

[3] As the CAI thesis would mean that ‘baseball = atoms arranged baseballwise’.

[4] Begging the question explanation: assuming your conclusion in the premises of your argument. Liam is always well understood. If liam writes badly, then he wont be understood. Therefore, liam writes mediocarly he will be well understood/ liam is always well understood. A better explanation is given here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OAXKc-rvMa8

[5] And that these redundant atoms have no effect themselves on the properties of being chairwise (or any other way wise?).

For a good example of a MetMo cube see: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bvOpyy70wY4 by MetMo on Youtube

For an example of how MetMo cubes are made see: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f9zyenX2PWk by Steve Mould on Youtube

Bibliography

Korman, D. (2015). Objects: Nothing out of the Ordinary. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Merricks, T(2001). Objects and Persons. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Vicente, A. (2004). “The Overdetermination Argument Revisited”, Minds and Machines, Volume 14, Pages 331–347.

Recent comments