Rhythms of identity and marginality: Exploring Slowed-Down Cumbia in Fernando Frías de la Parra’s I’m No Longer Here (2019)

by Laura Osorio Salazar

* Please click here to download a takeout version of this blog post

Since its invention as a new audiovisual medium in the 19th century, cinema has been a source of fascination in terms of its specificity as a medium, its impact on audiences and creators (now known as filmmakers), and its constant transformation over time with the advent of new technologies. There have also been several theoretical debates about film’s relationship to other arts with a longer history, such as literature, painting, and music. As an art of the moving image, some film studies theorists argue in favour of the universality and uniqueness of film, while others compare its components (angles, camera movements, use of sound, etc.) according to their impure and impure character, creating a “pattern of winners-and-losers” (Chion 4).

The truth is that cinema is the site of a heterogeneity of genres, practices, and audiences in which a single concept to define it is impossible. This is mainly due to the presence of different musical styles and approaches to musicality. They not only give life to films but, as part of a whole, shape their aesthetic and narratological choices. While the object appears to have an existence in real-time on the screen, music reinforces cinema’s “iconic sense of time” (Brown 17) to the viewer. In other words, when we watch a film, music helps us to understand the deeply stylised language of the story as a cinematic production.

Given the prevalence of music in today’s most popular films, I wondered how to listen to a film score and decipher its stylized, iconic sense of time, and whether music was just another element in the service of a larger narrative. The answer seemed simple at first: I had to go back to the film sequences and disseminate them note by note. But, contrary to what many people believe, analysing a film is not an easy task.

How could I approach much-discussed cult films to understand the importance of music in cinema? Or, more importantly, were there no other productions that raised new questions about representation, narrative, and/or aesthetics in film music?

With this in mind, I thought that instead of focusing on well- known cinema, we could learn how to listen to film music by exploring contemporary film repertoire that suggests new relationships between music and film —including its score as what is heard on diegetic and non-diegetic levels [1], and its innate musicality as a link between the moving image and sound as an instrument. New cinematographic choices imply new ways of hearing and seeing the well-known binarisms between what is shown and what is said on screen.

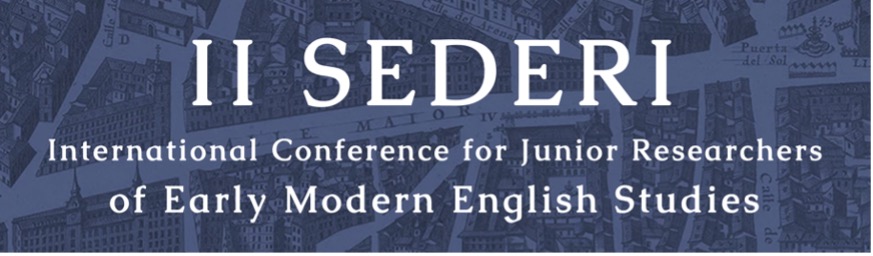

Figure 1. Official promotional poster for the film I’m No Longer Here, winner of the Ariel Award for Best Film, and Best Actor at the Cairo International Film Festival, among other awards and honourable mentions.

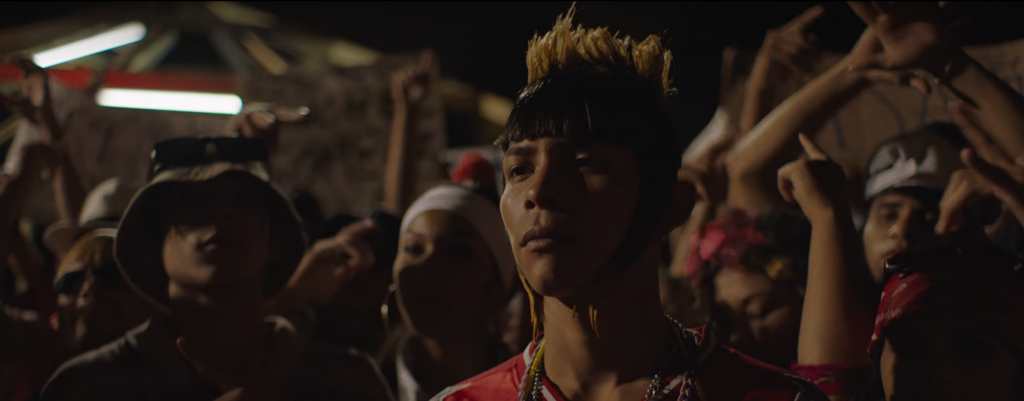

On this logic, the film Ya no estoy aquí (2019) —I Am No Longer Here as the official English title—, directed by the Mexican producer Fernando Frías de la Parra, may offer clues to a musical function little explored in cinema and mentioned by Michel Chion (2021): “the parenthetical value of music” (226), which inscribes its own temporality on the film. Far from interrupting the film’s narrative, however, these music parentheses allow the story to be mobilised in non-linear time. In this way, the story follows Ulises, a young man from Monterrey, Mexico, who belongs to the countercultural movement of the Kolombia, defined as those “natives of Nuevo León who live according to Colombian practices” (Olvera Gudiño 96). Together with their friends, the gang of Los Terkos (stubborn in English), they meet to dance slow cumbias [2] in the streets, wearing a multicoloured aesthetic that combines fashionable styles with their marginalised conditions.

After a misunderstanding between gangs, he is forced to flee his hometown and migrate to New Jersey. His only motivation for moving forward is his love for cumbia music, whose nostalgic melodies and hybrid rhythms take him on a journey through what was and what will never be. While I had to piece together a complex jigsaw puzzle of Ulises memory to understand the story, I noticed that the music operated in the background and “co-irrigated” (Chion 226) each scene with vitality and comprehension.

Later I understood why the term “irrigate” was appropriate to define the process by which the music narrativizes and mythologises the film. For the moment, I started by looking at the first few scenes and the relationship between the moving image and the music. At the beginning of I’m No Longer Here, we are confronted with a deeply emotional first scene: a boy in baggy clothes, whose name we do not know, is saying goodbye to his family.

To the boisterous sounds of an industrial Monterrey in the 2010s, one of his friends runs to see him off and gives him an MP3 player. Then she forms a star with her hands and declares: “Terkos forever” (1:50:05). This MP3 will be key to the plot, as it will build the entire score for the film. It also represents a combination of two of the three ways in which, according to Chion, music can be present in film: the sound that comes out of the MP3 “as something we hear but do not see in the performance, and the sound that we hear and simultaneously see being played and sung” (13).

Figure 2. In a long shot, Ulises leaves his mother to go to New York. In the background, we see Monterrey, a crucial industrial and musical centre for Mexico. Global Panorama, Netflix (2020).

Figure 3. Ulises says goodbye to his friend “Chaparra” while holding in his hand the MP3 player she gave him. Global Panorama, Netflix (2020).

Silently, I moved away from Monterrey and the scene cut to the present, where the boy and another Mexican migrant are looking for work in Mr. Low’s shop in Queens, New York. The music only reappears when Ulises calls a local radio station to send a message to his friends after failing to find a job. The fact that the music I have heard so far has only been reproduced through a technological device says a lot about the transformations and reappropriations of cumbia as a musical genre.

According to L’Hoeste and Vila (2013), when cumbia reached Mexico’s borders and was imbued with norteña music [3] —characterised by a strong rural accent—”it enjoyed early access to the technology and resources of popular music, which emphasise mass appeal, commercial value, an urban character and a bond to technological development” (88-89 with emphasis). The musical world of the early scenes was thus empowered by the uncertain rhythms of technology, the same that reinvented culturally rooted genres like cumbia and transformed them into transnational sounds.

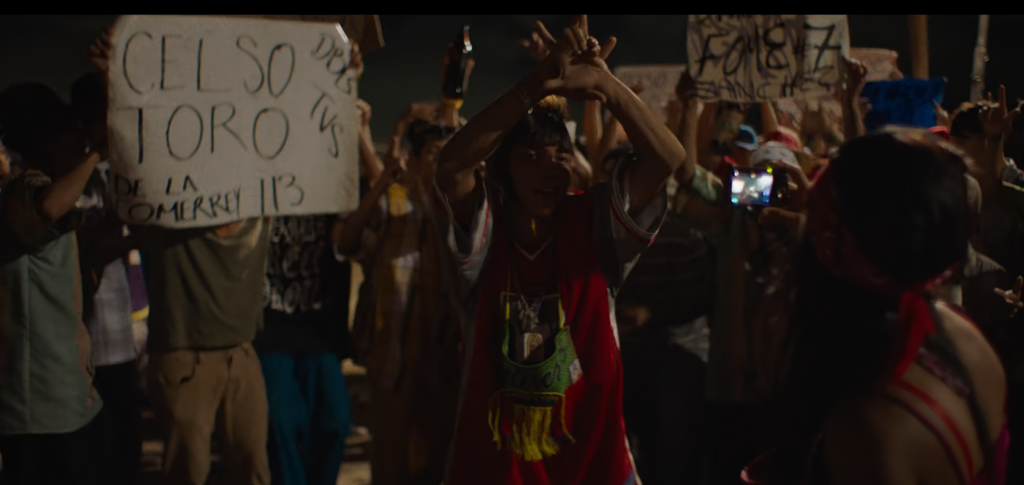

These ideas were materialised in the first dance scene of I’m No Longer Here, where Ulises and his gang start dancing to the rhythms of a cumbia rebajada (a slowed-down version of the genre) at a clandestine party. In an interview with the director, he claims that “for me, this music comes as the voice of resistance trying to make the song last a little longer, trying to hold on to that dance, trying to squeeze every drop of meaning out of it, because after that, the future is not so promising” (Frias 2021 with emphasis).

Figure 4. Ulises joins the clandestine party motivated by Chaparra and dances to the sound of cumbia. This space brings together other Kolombian gangs. Global Panorama, Netflix (2020).

Figure 5. For the first time on screen, we see the star symbol of the gang Los Terkos. This star represents the five points of the compass where each member lives. Global Panorama, Netflix (2020).

The music, as a metaphor for the desire to prolong a finite youth in which Ulises and his friends, as marginal subjects, are relegated to the slums and have no chance of social mobility, also becomes a “spatio-temporal apparatus” (Chion 205). This apparatus shows us, in a condensed form, the cinematic world that the director wants to create. Thus, always as part of a Whole, it circulates through space and time, creating a system of circulation in Which each scene is interwoven from the boy’s perspective.

At first, I was confused because the story did not unfold linearly. But by following the music we hear with Ulises on the MP3, we find a more evocative way of connecting his nostalgic memories as the film begins to jump from the past to the present and vice versa. In order to understand how the main character’s memory is constructed through cumbia music repertoire, I looked at three key sequences that might shed some light on how music forms a symbiotic relationship [4]with this film. The first shows the arrival of a new member of Los Terkos, called “Sudadera” because of his unfashionable clothes. To join the group, the little boy must prove that he genuinely likes cumbia, so he starts singing Lizardo Mesa’s Lejanía (1982) while Ulises and his friends accompany him on improvised instruments.

In his song, we find the nostalgic and sad feeling of those who lived in the countryside and had to migrate to Monterrey for various reasons: ” How I miss my beautiful savannah tucked into the mountain range (…), and in my chest a cumbia of nostalgia blossom/ as a tear that escapes” (1:32:33) [5]. His tearful singing contrasts with the question-and-answer system and effusive rhythms typical of cumbias. Nevertheless, this sequence made me understand the verbal nature of cumbias: although they are dominated by percussion, it is the lyrics that make them identifiable and ready to be appropriated.

In this sense, the song sung by Sudadera “encodes the visual/narrative fusion with the mythologies embedded in a particular culture” (Brown 30). Both this music, represented by the sung melody, and the cumbias that Ulises listens to on his journey, engaged with the visuals of the film to consolidate a mythified universe of nostalgia. Cumbia is the most important soundtrack, in contrast to other scenes where English rock and electronic music are heard because only its melody can transform the object-event in the film into an affective object-event.

Figure 6. Terkos, who use buckets, pencils and notebooks to imitate accordions, drums and cumbia melodies. Global Panorama, Netflix (2020).

This may explain why Ulises refuses to listen to and dance to other music when he arrives in the United States as the cumbia style stimulates his ability to remember what he once loved and what he once was: “The music is very lame” (30:42), he says when he is invited to a party by Lin, Mr Low’s granddaughter. However, this pinche music, as Ulises derogatorily calls it, is everywhere in the U.S., and his only escape is to cling to his last remaining trace of identity as a Kolombia, his MP3 player. Similarly, in his friendship with Lin, he refuses to learn English to communicate with her and even acts hostile to any sign of change while Lin tries to discover his style and music.

This corresponds to a frozen state of cumbia in Monterrey since the 1990s, where “young people continue to listen and dance to the old cumbias of Andrés Landero, Policarpo Calle, Los Corraleros de Majagual, Alfredo Gutiérrez and Lizandro Mesa” (L’Hoeste and Vila 97). The desire for everything to remain as it was comes not only from the character but also from the lowered cumbia itself, which changes every sequence of the film, even in the frames that remain still and last longer. As a character, Ulises “does not want the music to stop because there is no future, there is no hope, there are no possibilities, there is no way out of these situations” (4:24), according to the director.

Figure 7. Director Fernando Frías talks about his award-winning film and what motivated him to create this moving story about memory, nostalgia, migration and cumbia. The World Around, Youtube (2021)

The second sequence took me to Ulises and Lin as they fall asleep in the room on the roof above Mr Low’s shop, where the boy is hiding because he has nowhere else to go. As if in a dream, and to the rhythm of his MP3, he gives his body to the music, and for the first time we see how he manages to transport his body to the past when he danced in front of Los Terkos. The cinematic elements respond to this musical call, and the scene in the small, claustrophobic room merges with the dance scene in Monterrey. So, the scene continues, and he ends up dancing alone, with his beloved city in the background. At the same time, another unseen transition/transposition takes him to the New York subway, where he keeps dancing for money without leaving his musical trance.

Suddenly, a stranger yells at him to stop, bringing him back to the present, and he runs away, frightened. In this way, the film “creates worlds where music can appear out of nowhere or leave you without warning, filling your heart with haunting regret” (Chion 203). As part of the audience, I was able to interpret these silences and musical voids through the eyes of the stigmatised character, who seeks refuge in music and, failing to find it, his world falls silent.

Figure 8. Between 41:34 and 40:15 of the film we see one of its most beautiful sequences. In the first scene, we see the image of Lin and Ulises fade into another scene of him dancing with his friends. In the middle scene, we see him dancing alone to the sound of cumbia. The third scene ends with another fade-out that transports Ulises’ body to the New York subway. The slowed-down version of the song “Besos sobre besos” (1970) by Anibal Velásquez ties the whole sequence together. Global Panorama, Netflix (2020).

This is only one example of how the visuals and music are brought together by the narrative “to elicit emotions (and become an affect-object event) and make the viewer believe in the reality of what they are seeing” (Brown 23). This unleashed emotion not only blossoms within me as the observer but also within Ulises, as he realises that the world denies his existence and does not allow him to be. When the music disappears, new fears arise in him, while in later scenes Lin asks him if the reason he didn’t return to the subway was because he didn’t like dancing alone. Cumbia is, therefore, the only thing that allows him to continue resisting, creating “a big persona that affirms himself and allows him to respond to social stigmatisation and marginalisation” (Frías 2021).

Yet Ulises cannot find a sense of belonging in a place that blurs his true identity, leading him to part ways with Lin and wander the desolate streets of New York in a state of despair. In this moment of solitude and silence, he has an identity crisis and decides to cut his distinctive hair to break free from a past lost in the imposed flows of time. Alone with Lizandro Mesa’s “Te llevaré” (1984) playing on his MP3 player, he chooses to lose himself in the memories of how he crossed the border: “You were left crying/because you can’t travel with me/but I’ll carry you in my heart/I’ll carry you here in my song” (16:45) [6].

Cumbia as a musical score is represented as the love left behind. This means that the songs Ulises listens to are only echoes of their rhythms, and the engine of his memories has become pure nostalgia. As such, the music in I’m No Longer Here “seems to enter as an imaginary source of the movement of images whose real source is mechanical projection” (Chion 233 with emphasis). Following this logic, I moved on to the final sequence, in which Ulises’ dance performance and the cumbia music become one in the narrative, and the symbiotic relationship becomes even more palpable.

Scene 6. In an almost silent scene, Ulises is picked up by US immigration authorities and sent to a deportation centre in Mexico. Global Panorama, Netflix (2020).

While walking the streets, the protagonist is found by the authorities and deported to Mexico. After several months in detention, he returns to Monterrey to face a harsh reality: his friends are now part of violent criminal gangs, and the marginalised cumbia no longer fills the streets where he used to dance.

As a viewer, I Wondered how he would return home, to what he once loved. However, the answer was always in the music.

With the sounds of riots, screams, and violence in the background, Ulises decides to climb to the top of a hill and put on his MP3 headphones to listen to what we know will be his last song. Between a combination of medium-long shots and wide shots, we see him dancing to Monterrey in a slow and melancholic way. In this scene, with the beautiful use of camera, I was reminded of how cinematic narrative is fictionalised through highly manipulative and subjective filmmaking processes. However, fiction is not understood as untruth, but as consciously constructed, with artifice and carefully stylised elements.

Scene 7. Ulises puts on his MP3 headphones to listen to the cumbia song “Quiero decirte hoy” (2018) by Octubre 82 and dances to an unfamiliar and alien Monterrey that he once called home. Global Panorama, Netflix (2020).

Ulises experience is deeply human and emotionally motivated in a world that condemns him for his social condition, the way he dresses, and the music he likes to listen to. His story, through the embodiment of music as a narrative driver, shows a variant of reality that is forgotten on the margins of society. If we consider music in the film “in relation to the continuum of speech through breaks, interruptions or silences” (Chion 247), then we could argue that these fictionalised spaces allow cumbia to flourish and, along with other cinematic elements such as camera angle and dialogue, co-irrigate all its potentialities on screen.

Scene 8. A crashing and colossal Monterrey is compared to the dancing figure of Ulises. However, he doesn’t stop to move to the cumbia rhythm until the music is abruptly interrupted by the lack of battery in the MP3 player. Global Panorama, Netflix (2020).

As a result, Ulises’ dance only ends when his MP3 player’s battery runs out, leaving him to contemplate the sounds of a strange city that he can no longer call home. Metaphorically, even before it was cut, the song conveyed his sense of alienation: “I want to tell you today/That I no longer love you/That I no longer miss you” (9:14) [7].

Certainly, talking about the relationship between music and cinema in the film I’m No Longer Here (2019), by Fernando Frías de la Parra, led me to think about cumbia as a musical genre and its influence both on the music scene in Monterrey and on the cinematic analysis of each scene. Cumbia has been forged in between legitimacy, relevance, and national and transnational identity. With its varied rhythms and nostalgic lyrics, it also became an emblem of the Mexican migrant experience. In the film, cumbia is heard as the main soundtrack only through technological devices such as Ulises’ MP3 player and the radio. However, despite being limited to its medium, it manages to wreak havoc on the protagonist and become the driving force of his memories.

In this blog, I used the word co-irrigate to define how music permeates the screen, making it flourish by reinforcing its fictional worlds. I also argued that it narrativizes and mythologises the chain of affections that are produced in us as viewers. In this way, I firmly believe that music becomes a means of resistance in which Ulises and Los Terkos, in the words of Guillermo Del Toro in a Netflix interview with Alfonso Cuaron (2020), “understand that they are oppressed by many things, but for the moment they are dancing, they are alive. That’s the existence of making a film in Mexico. Things are against us, but for the moment we dance” (14:30 with emphasis).

Directors Guillermo del Toro and Alfonso Cuaron discuss the work of new Mexican filmmaker Fernando Frías de la Parra and his first feature film, I’m No Longer Here. The film is available on Netflix with English subtitles. Netflix (2020)

The cumbia music embodied in the Kolombia contraculture as the main soundtrack is just one way of redirecting studies of music and film towards disruptive cinematic proposals with great social potential that make visible the power of fiction in reality. Perhaps, beyond showing the pornomisery [8] so familiar in Latin American productions, the film constitutes an ode to how cumbia has been appropriated in Monterrey. An ode to life, to memory, to eternal exile and the popular songs of historically marginalised classes.

References:

Brown, Royal S. “Narrative/Film/Music.” Overtones and Undertones: Reading Film Music, U of California P, 1994, pp. 12-37. JSTOR, https://doi-org.eux.idm.oclc.org/10.2307/jj.2711586.5

Chion, Michel. Music in Cinema, New York Chichester, West Sussex: Columbia University Press, 2021. https://doi- org.eux.idm.oclc.org/10.7312/chio19888

De la Fuente, Anne Marie. “‘I’m No Longer Here’ Director Fernando Frias Talks About the Mexican Film Biz.” Variety, March 2, 2021. https://variety.com/2021/film/news/mexicos-fernandofrias-im-no- longer-here-1234912782/#respond.

Del Toro, Gullermo, and Cuaron, Alfonso. “Ya No Estoy Aquí: A Talk with Guillermo del Toro and Alfonso Cuaron”. Netflix, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1FHtkn9hamk

Fernández-L’Hoeste, Héctor D., and Pablo Vila. Cumbia!: Scenes of a Migrant Latin American Music Genre. Durham: Duke University Press, 2013.

Frías de la Parra, Fernando. Ya No Estoy Aquí. Netflix, 2019, https://www.netflix.com/gb/title/81025595

Footnotes:

[1] According to Michel Chion (2021), diegetic music belongs to the action shown on the screen, while non-diegetic music comes from an imaginary source not present in the action.

[2] In the introduction to their book Cumbia! Scenes of a Migrant Latin American Music Genre (2013), Héctor Fernández L’Hoeste and Pablo Vila define cumbia as a genre that was born on the coast of Colombia and, as a product of the creolisation of different cultures, mix Amerindian, Spanish and African musical traditions such as percussion. It is also part of the so-called rhythms (ritmos) of the Atlantic coast of Colombia, along with chandé, and bullerengue.

[3] Norteña music is a sub-genre of Mexican regional music, characterised by using the accordion and bajo Along with Colombian cumbia, it is one of the genres that has most influenced the music scene in Monterrey, Mexico’s symbolic industrial capital.

[4] By symbiotic relationship, I refer to the biological sense in which two or more organisms interact in different ways to survive. Specifically, I believe that the relationship between music and film is defined as mutualism, as both media benefit from each other and create fictional worlds out of their active dialogue.

[5] In the original version: “Como extraño mi sabana hermosa metida en la cordillera (…), y en mi pecho ofreció una cumbia de la nostalgia/ como una lagrima que se escapa”

[6] In the original version: “Tú te quedaste llorando/porque conmigo no puedes viajar/pero yo te llevaré en mi corazón/ te llevaré aquí en mi cantar”.

[7] In the original version: “Quiero decirte hoy/que ya no te quiero/que ya no te extraño”.

[8] Pornomystery is understood as a way of exhibiting violence and marginality to generate morbidity in the public, especially around the pain and suffering of the victim.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Laura Osorio Salazar is a writer and artist from Colombia who works in a variety of media, including drawing and printmaking. She holds an MSc in Intermediality Studies (University of Edinburgh, 2024). Her work engages with postcolonial studies, particularly creolisation, focusing on embodiment, discursive and performative voices, and ways of being in the world beyond official narratives. She is co-founder of In/Between Journal, a platform for interdisciplinary and inter-media creation that brings together diverse academics and artists. She is also interested in the dialogue between digital humanities and analogue art, exploring the intersections between the two.

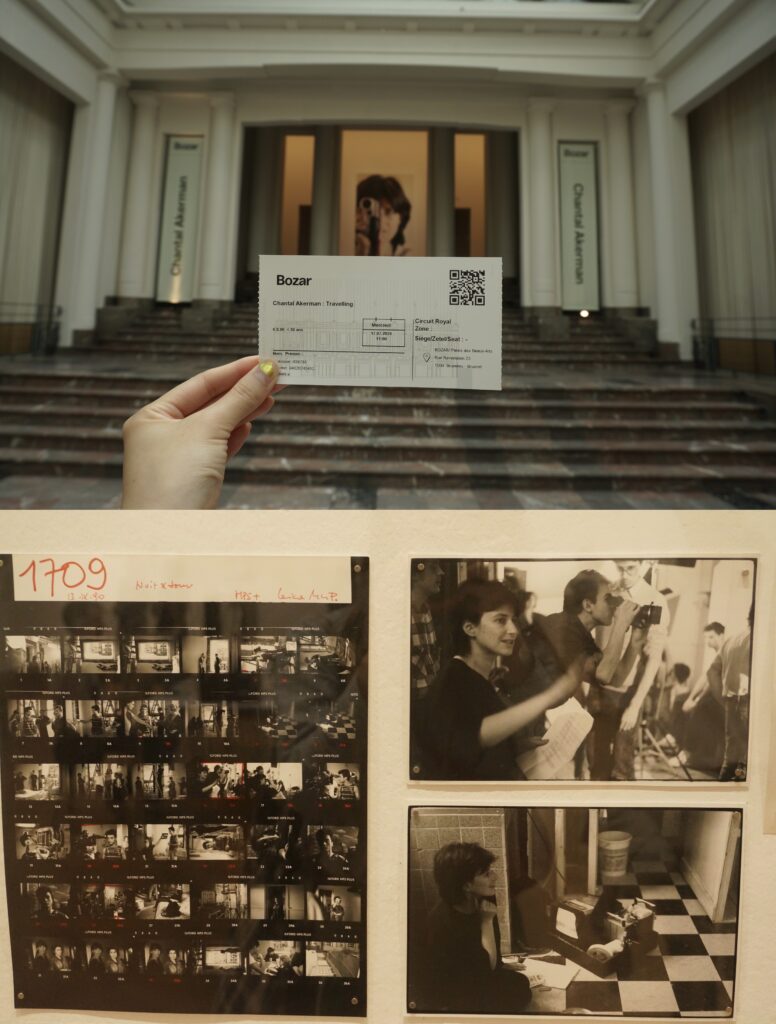

Travelling with Chantal Akerman

by Jianing Liu

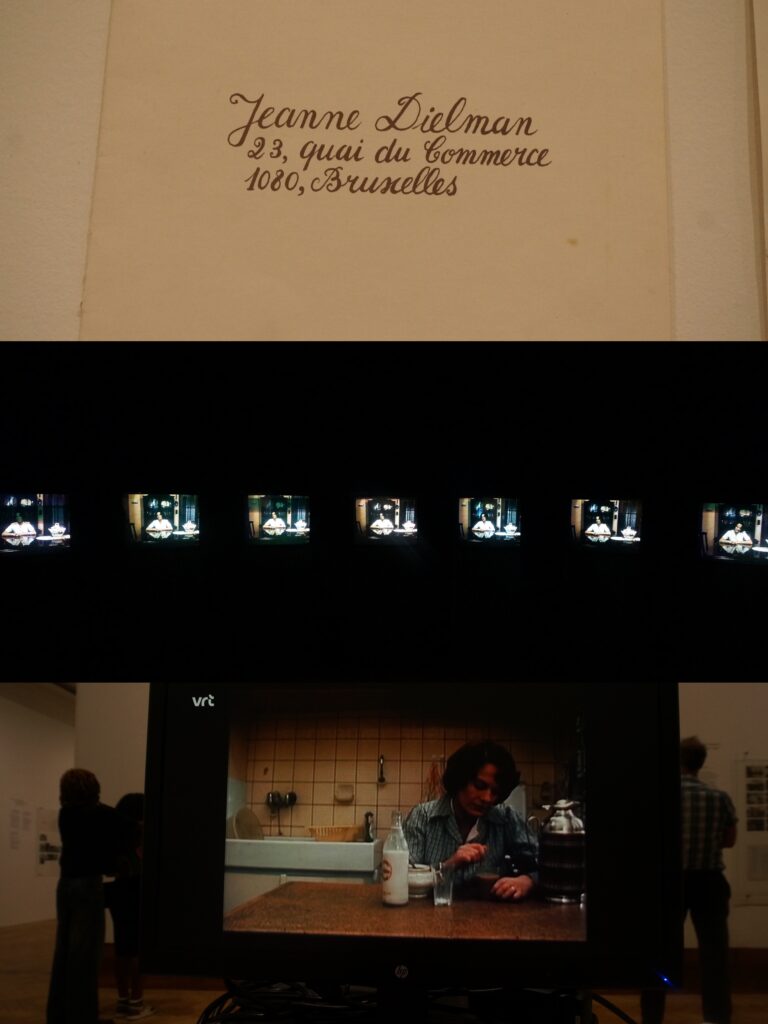

In the middle of July, I paid a visit to Brussels, the home city of Belgian filmmaker, writer and artist, Chantal Akerman. The journey left me with a lingering feeling, as a retrospective exhibition at Bozar intersected with my own trajectories to map out Akerman’s filmic city, and this lasting feeling inspires me to write something to channel these travelling memories.

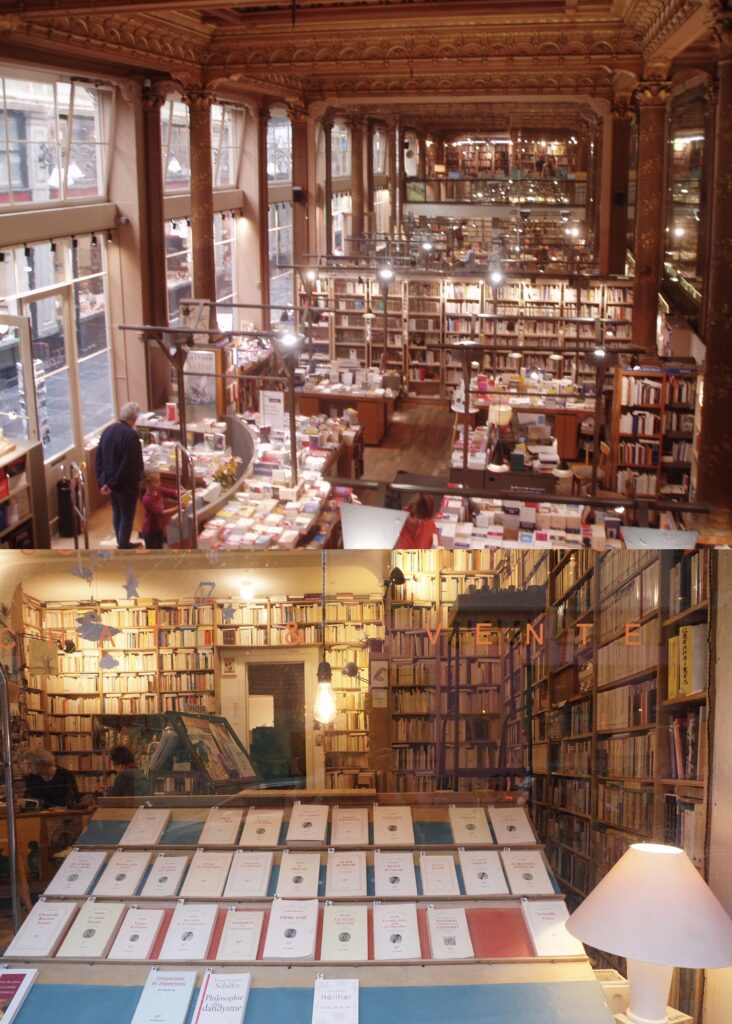

The exhibition, entitled “Chantal Akerman: Travelling”, at Bozar, the Centre for Fine Arts in Brussels traces Akerman’s nomadic film trajectories starting from her “mother-city” Brussels to Paris, the wellspring of her creativity; from the harsh winter in Eastern Europe to the vastness of the Mexican desert, and departing with a fading cityscape of New York. For me, Akerman captures the cities as if she scattered her nomadic identity to drifting non-places. Sometimes it is impossible to discern where she locates her camera: the streets are always deserted, always empty; people are always restless. The urban spirit is like the sultry night she evokes in Toute une nuit (All Night Long, 1982) draped in a filmic fabric, as tangible as the deep blue silk, leaving no respite for sleeplessness. As for Brussels, it is the nurturing cradle where she spent her teenage years, and where she paved her peripatetic journey among bookstores, cinemas, and train stations, exploring her identity and queer expression.

The exhibition handout writes the significance of this city in Akerman’s filmmaking: “Born in Brussels in 1950, Chantal Akerman was one of the first filmmakers to regularly use this city — the place of her birth and the very fabric of her work — as a film city in its own right, rather than just a passing backdrop.”

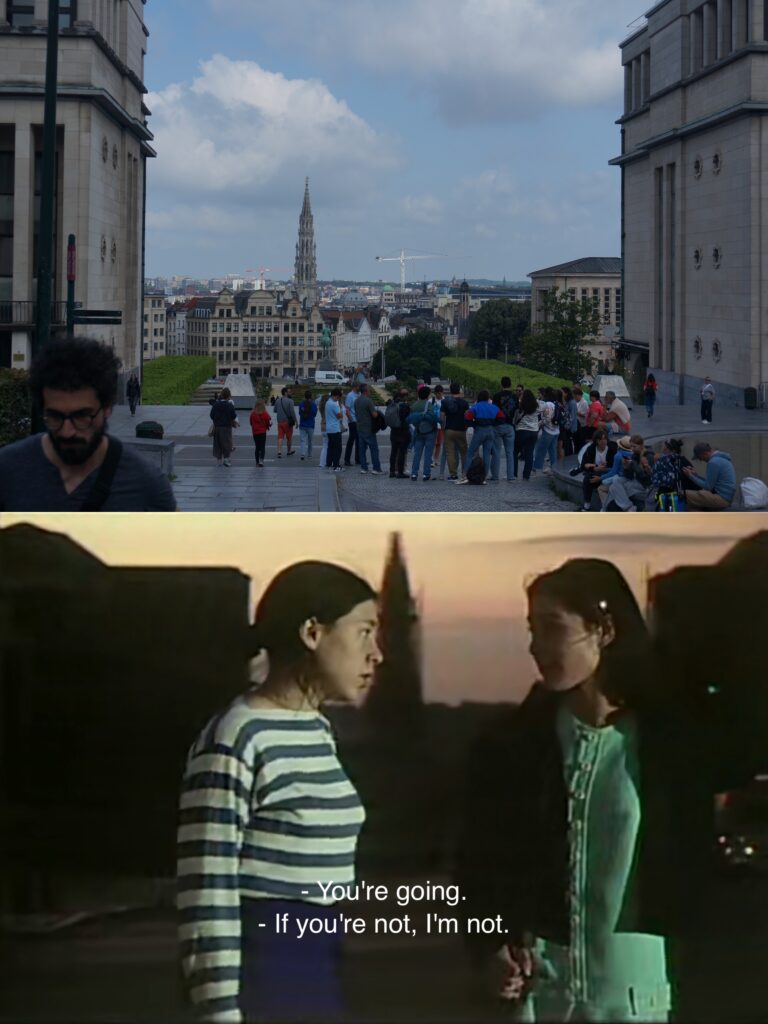

All Night Long & Portrait of a Young Girl at the End of the ‘60s in Brussels

The fabric of the city is deeply felt when one roams through it, as the texture of its architecture flows together with the emotional fabric of her films. In the film Portrait d’une jeune fille de la fin des années 60 à Bruxelles (Portrait of a Young Girl at the End of the ‘60s in Brussels, 1994), instead of serving as mere backdrop, the city of Brussels is captured as the sentimental symphony of the characters. And in my journey, these places become half-real and half-fantasy, as I initially passed by but was drawn back by a subtle echo between film and reality. In an inadvertent glance back, film endows the city with a tender look, a retrospective nostalgia.

- Film and reality

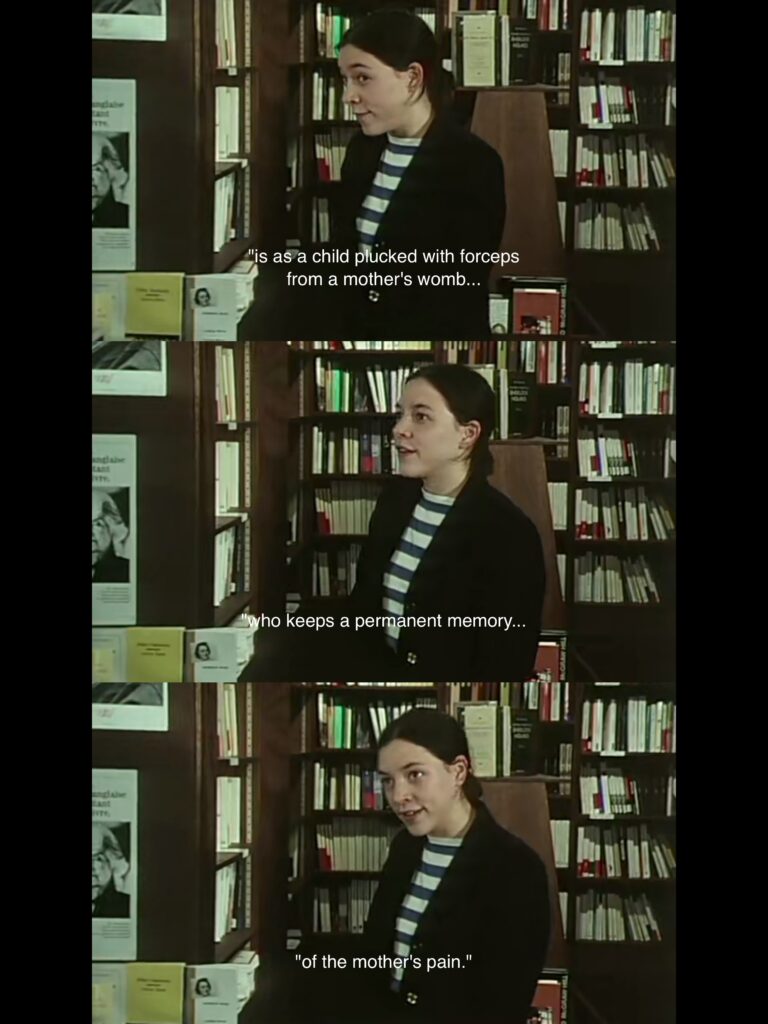

The relationship between the self and the city turns out to be a complicated theme explored by Akerman. The connection with Brussels can be compared to an invisible bond between mother and daughter — intimately inseparable yet immediately painful. In one scene where the girl and the boy stroll to a bookstore, this introspective girl philosophically reflects on this complexity: “It is as a child pucked with forceps from a mother’s womb, who keeps a permanent memory of the mother’s pain.”

- Portrait of a Young Girl at the End of the ‘60s

- Beautiful bookstores in Brussels

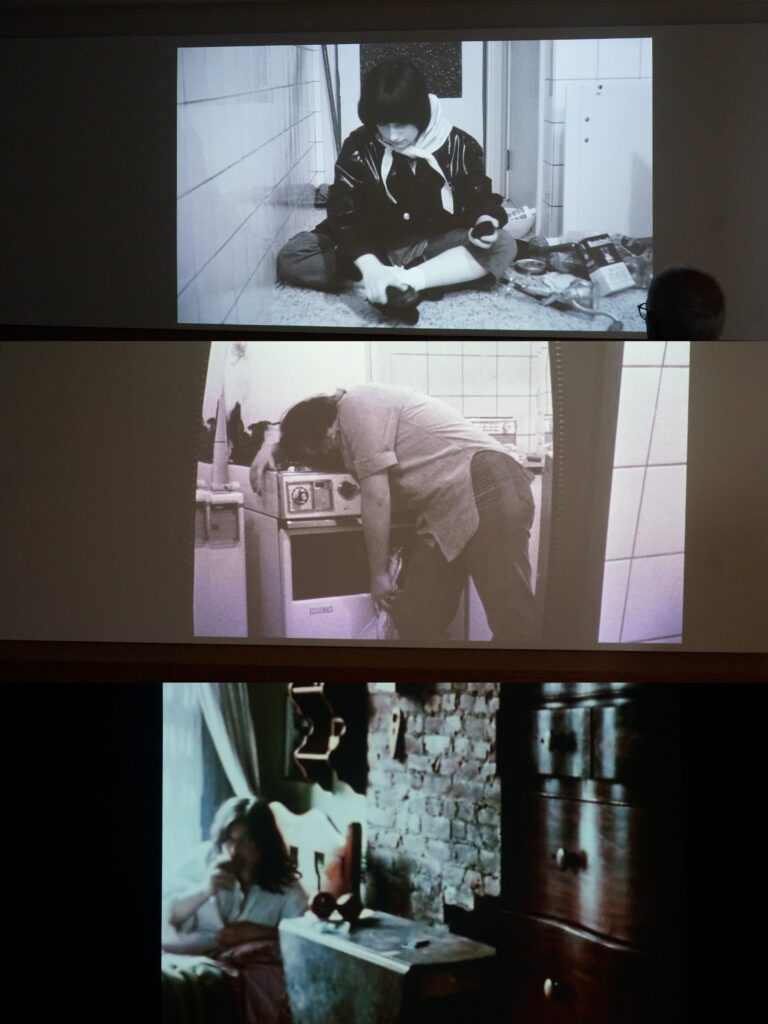

In addition to the exterior city-wanderings dealing with growing pain, Akerman’s camera penetrates into interior space, to women hidden in the most ordinary corners, unveiling the restlessness trapped within the city. Whether through the rotating camera in La Chambre (The Room, 1972), destructive self-abuse in Saute Ma Ville (Blow up My Town, 1968), or the calmly static body gestures of Jeanne Dielman –the woman sitting after killing – interior places such as kitchens or bedrooms are integral compositions of her film fabrics, where women cook and also kill.

- Jeanne Dielman

The most impressive journey for me was from the art installation of her documentary film D’Est (From the East, 1993), where screens in rows line up like a train, taking the audience to the snowy winter streets of Moscow. Only by walking into the darkness of the exhibition hall, pacing between flashing screens, staring on frostbitten faces, paying attention to shifting sounds — people’s murmuring on streets, melodies from the cello and the silent falling snow – can one feel the intermedial essence of this journey, with the materiality of the images, and the textures of coldness, becoming palpable.

The most impressive journey for me was from the art installation of her documentary film D’Est (From the East, 1993), where screens in rows line up like a train, taking the audience to the snowy winter streets of Moscow. Only by walking into the darkness of the exhibition hall, pacing between flashing screens, staring on frostbitten faces, paying attention to shifting sounds — people’s murmuring on streets, melodies from the cello and the silent falling snow – can one feel the intermedial essence of this journey, with the materiality of the images, and the textures of coldness, becoming palpable.

Here is a video showing my immersive experience.

Akerman, with her nomadic spirit, gives me courage to traverse physical and psychological borders. Standing in front of her filmic images feels like standing before a mirror, completely naked and genuine, astounded by the frankness of one’s own body, consciousness, and self.

Jeanne Dielman mural in Rue Saint-André

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Jianing Liu is a graduate student in Intermediality Studies at the University of Edinburgh. She holds a BA in English Translation from Donghua University (Shanghai) and enjoys film, museums and aimless travel.

All That We Are Is What We Hold in Our Outstretched Hands: Tuan Andrew Nguyen’s Meditation on Memory

by Julia Larsen

While Nguyen seems to say it is impossible to accurately recall the past, he also seems to say that there is still value and truth in the stories we are able to tell about the past, availing himself of the intermedial dimension of installation art through the combined use of narrative media.

When you enter Tuan Andrew Nguyen’s exhibition at the Centre for Contemporary Arts in Glasgow, you enter the realm of the remembered. The exhibition, titled All That We Are Is What We Hold In Our Outstretched Hands, takes you on a journey through memories that are not your own – and some that truly belong to no one. Nguyen explores the way memories occupy a space between fact and fiction, and often become a third thing entirely: something imagined yet true.

This exhibition showcases a particular slice of history for two colonized nations: the Senegalese-Vietnamese community that emerged when tirailleurs sénégalais, Senegalese soldiers conscripted to fight for the French in the First Indochina War, married and had children with Vietnamese women while stationed in Vietnam. Some of these soldiers brought their wives and children back to Senegal when the war ended; others brought only their children and left the women behind. The story of this community is one of complex geopolitical movements born from the violence of colonialism, but also of deeply personal choices individuals needed to make within the context of colonial oppression. Nguyen’s work makes the geopolitical personal.

All That We Are consists of three parts, each in a separate space: the first room holds two films (Our Empty Uniforms Marched To The Echoes Of An Invisible and Mother, Métis, Memory), the second a four-channel video installation (The Specter of Ancestors Becoming), and the third contains a gallery of family photographs.

Tools of memory, from archival footage to family photographs, permeate all the pieces in this exhibition. The first film installation, Our Empty Uniforms Marched To The Echoes Of An Invisible, juxtaposes two sets of archival footage, remembering the First Indochina War from the opposing perspectives of the Senegalese soldiers and the Vietnamese soldiers. This footage highlights at once their differences and their similarities, creating a unified narrative across two sides of a war. The second film, Mother, Métis, Memory, is made up of a series of interviews with the Senegalese-Vietnamese community recalling their heritage and family stories. The photo gallery is perhaps the most visceral proof of memory. Formal engagement photos and military portraits hang next to candid shots of parties and family portraits. The photographs are displayed without plaques, giving a simultaneous feeling of intimacy and anonymity. The lack of labeling makes the gallery reminiscent of family photos hung on the walls of a home; however, these people are not known to the viewer, transforming what would be familiar portraits into anonymous images.

The photographs are displayed without plaques, giving a simultaneous feeling of intimacy and anonymity. The lack of labeling makes the gallery reminiscent of family photos hung on the walls of a home

The Specter of Ancestors Becoming, the four-screen installation at the center of this exhibition, utilizes narrative as a tool of memory. Here, memories are portrayed as fiction, at once truth and myth. The installation consists of three different narratives, each written and told by a different person and illuminating a different facet of the Senegalese-Vietnamese community. These narratives are portrayed as memories, although they are fictional. The first story shows a husband and wife deciding whether to stay in Vietnam or migrate to Senegal now that the war has ended; in the second, positioned thirty years after the first, a son confronts his father after discovering the real identity his biological mother, a Vietnamese woman left behind by his father upon his return to Senegal; and in the final story, a girl and her grandmother, now firmly established in Senegal generations later, recall a mixture of true and fictitious memories of the First Indochina War. One of the screens shows the speaker reading the “memory” they have written, while the action of the memory is played by actors on the screen directly across. The two screens on the sides show a mixture of individuals from the contemporary Senegalese-Vietnamese community, often configured as a family, interacting with each other in the present or holding photographs of people not present, presumably the Vietnamese women left behind by their Senegalese husbands.

These narratives are portrayed as memories, although they are fictional.

The specter of absence looms large in both the stories and the images of the piece. Abandoned mothers and wives are present on screen either as portrayed by an actor or in a photograph, but never as themselves. Their legacy is present in their descendants, but their physical selves are absent from the work. For the women who did migrate to Senegal, the specter of Vietnam remains. To migrate to Senegal is to forsake Vietnam, making a specter of your homeland; to remain in Vietnam is to forsake your potential future in Senegal, and become a specter yourself.

With the way the screens are arranged, it is impossible to see the whole installation at once. As a viewer, you must choose which portion of the narrative to pay attention to. To look to the past, you must turn your back on the present, and vice versa. The experience of stringing together different narrative puzzle pieces to create meaning mirrors the way we navigate threads of memory and create new narratives through remembering, misremembering, and imagining events we did not personally experience. Just as it is impossible for a Vietnamese mother to teach her children everything about her home country when they have spent their whole lives in Senegal, it is impossible for descendants to know everything about their ancestors when they have not lived through the same experience. For these migrant women, their homeland exists only in memory; for their children, it exists only through story. Vietnam becomes something remembered and imagined, dwelling more in the realm of the fictional than the real – much like our ancestors become when they pass on.

With the way the screens are arranged, it is impossible to see the whole installation at once. As a viewer, you must choose which portion of the narrative to pay attention to. To look to the past, you must turn your back on the present, and vice versa.

All That We Are Is What We Hold in Our Outstretched Hands meditates on the way we remember, misremember, and imagine the people and places who came before us, but also on the power of story and constructed narrative to keep memory alive through the combined use of photography, film and performance. In some way or another, history is mediated through tools of memory in each piece of this exhibit, presenting stories of the past rather than an accurate history. However, that does not make these stories any less true. While Nguyen seems to say it is impossible to accurately recall the past, he also seems to say that there is still value and truth in the stories we are able to tell about the past, availing himself of the intermedial dimension of installation art through the combined use of narrative media. This is, in part, because of the inevitability of becoming stories ourselves. One day, all that will remain of us is our face in a photograph and our words in someone else’s memory.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Julia Larsen is a graduate student of Intermediality Studies at the University of Edinburgh, an English teacher by trade, and a lifelong lover of learning. You can often find her crocheting while watching a scary movie, or taking her dog on a walk through the local cemetery.

¡Hola Madrid! Presenting at My First Academic Conference

by Xinyi Chen

Madrid became real to me when I was sweating in my waterproof jacket in the airport shuttle, thinking of my presentation for the upcoming SEDERI conference that would take place over the next three days — from the 5th to the 7th of October 2022 — at the cultural center ‘La Corrala’; an international conference for early career researchers co-organised by the Spanish and Portuguese Society for English Renaissance Studies (SEDERI) and the Autonomous University of Madrid (UAM).

Conference logo superimposed over a map of 16th century Madrid

A few months before travelling to Spain, I was taking the course ‘Global Shakespeare Across Media: Performance, Cinema, Digital Cultures’, part of the MSc Intermediality and offered across MSc programmes at the University of Edinburgh. I wrote an abstract based on my final essay for this course and I submitted it to the SEDERI organizing committee, simply through the link Inma, my tutor, attached in her email when she shared the call for papers with us. With my proposal getting accepted, I started to expect my first conference!

Conference folder and badge

It’s overwhelming to think of what’s waiting for me: socializing with other researchers, speaking publicly in front of experts in the field, getting questions that I may be unable to answer, etc — it’s too intimidating to look forward to. To get distracted from the anxiety before setting off to Madrid, I preoccupied myself with the possibility of getting rejected for my visa application, which would have been a perfect excuse for not attending. Thus, the trip to Madrid was spiritually never a certain event for me, until the last day in Edinburgh when I received a lovely email from Inma, wishing me all the best for the conference and encouraging me to approach and say hi to some of her dear colleagues in Shakespeare studies, such as Dr Reme Perni, who was also attending the conference and who, coincidentally, ended up chairing my panel! While Inma’s email reminded me of the imminence of the conference, I found myself in a very familiar situation of procrastination, coming back home from my part-time job at 9 pm; my traveling backpack still lying empty on the carpet, waiting to be packed, and there was only one slide in my presentation for the paper, with an exquisitely styled background and an unevenly sized title. Confidently, I flew to Madrid (irony intended!). Soon after I checked in at the venue, I found myself holding the conference package with the programme in my hands.

I joined the coffee break (where I could casually talk to different people with free refreshments available) which I later found out to be my favourite part of the conference. Having enjoyed all the coffee breaks, here are some reflections:

- First and foremost, the chocolate palmier is the best, even better with almond milk.

- Second, a successful eye contact means a conversation ready to take place.

- Third, it’s natural to start the conversation with the presentation dates and paper topics after introducing ourselves to each other.

- Fourth, we were actually not very good at recognizing names or faces; we tended to recognize each other by paper topic.

- Fifth, it’s important to be a good listener.

- Lastly, if I find it awkward being silent during a conversation, it’d become like 10% less awkward if I grabbed things to eat instead.

The ideas of others were interesting enough to let me pass the first two days in a carefree excitement (as I was going to be the last speaker to present on the third day). I even got a chance to watch a football game in person during the first night. It was of course another kind of excitement to cheer for Real Madrid in Santiago Bernabéu Stadium.

Xinyi’s impressive view at the stadium

Nevertheless, I still had to spend some time every day sitting in a Starbucks to prepare my own talk for the conference. What really motivated me to prepare was that I found the conference to be an intermedial space that would accommodate my ideas better than my paper ever did. Writing on contemporary film adaptations, I no longer had to refer to a scene by awkwardly describing it; rather, I could illustrate my analysis with screenshots and clips. When I was inserting pictures, videos, and quotations with Microsoft PowerPoint, I was pleased that the slideshow — despite being a presentation cliché — is such a great invention that’s going to give life to my ideas! Loaded with passion, I saw a flag of Scotland in the sky on my way to the Starbucks! Fingers crossed!!

A Scottish flag supporting Xinyi from the Spanish skies

Museum of Popular Arts and Traditions at La Corrala

I have to confess that I skipped the morning sessions on the third day; I wandered in the museum instead at the venue. I was crept out by these giants, badly frightened of their gazes from above. When I was about to run away, I met an intellectual bro who was similarly skipping the morning sessions and killing time in the museum. We talked about Catholicism, carnivals, Shakespeare, and Mikhail Bakhtin, though our knowledge only allowed for an interesting brainstorm. Since then, I’ve started to enjoy the creepiness of those carnival giants (as a way to survive them)!

It feels great to attract attention as a speaker in the conference session, especially when I didn’t feel myself in any way to be judged or graded. I felt rather supported and encouraged as an emergent researcher. Though I found it hard to answer the questions in the Q&A session, they were actually very good questions that have continued to provoke thoughts after the conference itself closed. While I had been so focused on my paper to construct a strong argument, those question brought new dimensions and even let me see the potential of new research projects. I see the questions as a way of support which I super appreciate (Thank you, Carlos, Yueqi, Reme, and Anna!). Also, in the first two days I was sometimes asked a question that I hadn’t been asked for a long time, ‘Are you nervous?’ Although I wasn’t, as long as I didn’t think of my own presentation, it was sweet that one could still talk about feelings at a conference.

A group picture of Xinyi (top right) with fellow conference speakers

Yayyyy also for those who had to leave early and couldn’t appear in this photo! The conference was exhausting. My mind hibernated as soon as the conference finished. I really wanted to fly back to Edinburgh immediately, but I had to stay in Madrid for another two days as I had scheduled my flight on the 9th and the conference finished on the 7th Oct. I was tempted (by tiredness) to stay in the hostel for the next two days, but I decided to get around when I thought of my single-entry visa — I definitely would like to make the most use of it to visit the city! Here is a photo to prove that I did go sightseeing in Madrid:

Xinyi at Madrid’s main square, la plaza mayor

By the way, Picasso’s Weeping Woman in the Museo Reina Sofia made my mind alive again!

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Xinyi Chen has recently graduated with an MSc Comparative Literature at the University of Edinburgh (2022). She also holds a B.A. in English Language and Literature from Minzu University of China. Xinyi takes an interest in Intermediality, loves Shakespeare and lives by curiosity.

My 3 Days in Cannes

by Kay Barrett

Kay on the glitzy red carpet at the 2022 Cannes Film Festival

In mid-May, I fulfilled one of my dreams: attending the Cannes Film Festival. As an American outside of the film industry, a ticket to Cannes seemed unattainable, like a bucket list item that would never come to fruition. Imagine my surprise when I researched Cannes internships on a whim and found the 3 Days in Cannes accreditation.

For the uninitiated (aka me, six months ago), the 3 Days in Cannes accreditation is a festival pass for film lovers between the ages of 18 and 28. To apply, you only have to submit a personal statement about your cinephilia, and I knew plenty of successful applicants who were not even studying film or media. Needless to say, I leapt at the opportunity to escape to the French Riviera for a cinephile’s dream excursion.

During my time in Cannes, I watched seven films (three were world premieres!). For the red carpet premieres, I paraded up the Palais de Festivals’ steps in my black tie attire, just a stone’s throw away from some of my favorite stars. In fact, walking the red carpet in and of itself constitutes a cinematic experience as you witness the montage of air-brushed celebrities posing before eager press members.

As for the viewings themselves, I was thoroughly unprepared for Cannes’s peculiar audience culture. For premieres, the audience stands as the cast and crew enters the screening, and we applause intermittently throughout the film’s opening credits. No matter the film’s quality, we’re also expected to give a standing ovation during the closing credits. This ritual framed each screening as a celebration and also highlighted the cultural investment of everyone involved. While I grew accustomed to streaming films online in my room during the pandemic, this experience reminded me of the joy of watching a premiere with a full, invested audience.

Just for fun, I’ve listed of the films from best to worst:

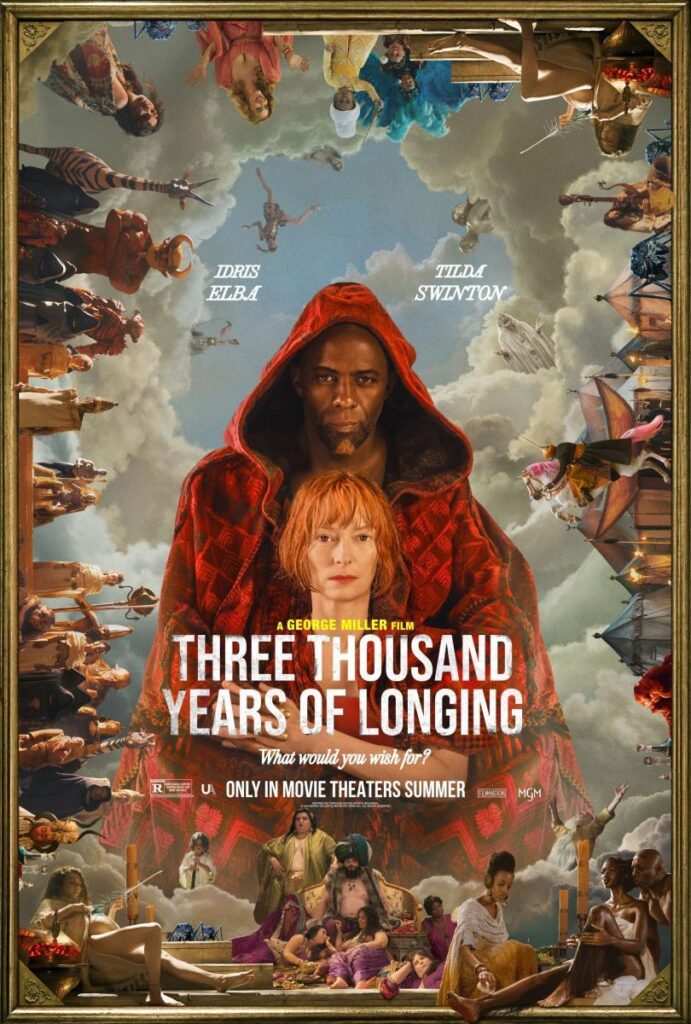

- Three Thousand Years of Longing, a romantic fantasy film about a literature professor and a djinn (dir. George Miller, starring Tilda Swinton & Idris Elba)

- Hunt, a Korean spy thriller of The Departed proportions (dir. Lee Jung-jae, starring Lee Jung-jae & Jung Woo-sung)

- Top Gun: Maverick, the sequel to the iconic 80s film (dir. Joseph Kosinski, starring Tom Cruise & Jennifer Connelly)

- Coupez!, a zombie comedy (dir. Michel Hazanavicius, starring Romain Duris & Berenice Bejo)

- EO, a cerebral indie flick about a wayward donkey (dir. Jerzy Skolimowski, starring…donkeys)

- This is Spinal Tap, a 1984 mockumentary about an irreverent rock band (dir. Rob Reiner, starring Christopher Guest & Michael McKean)

- Plan 75, a Japanese dystopian film set in the not-so-distant future about a government plan which encourages seniors to euthanize themselves (dir. Chie Hayakawa, starring Hayato Isomura & Chieko Baisho)

If you cross-check my rankings with critic reviews and IMDb scores, you will probably notice that I vary from popular opinion. This is the beauty of Cannes though. I viewed these films with no preconceived notions, no critics’ perspectives tainting my own interpretations. We talk a lot about ‘purity’ in intermediality, and I believe attending Cannes was the most pure experience of cinema that I could ever hope for. I will always cherish my brief stint in the south of France, and I hope others too will pursue this wondrous opportunity.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Kristen “Kay” Barrett is a graduate student in Intermediality Studies at the University of Edinburgh. She holds an MSt in English Literature from the University of Oxford and a BA in English from the University of Virginia. When not reading a book, she can be found watching a movie (and vice versa). You can find more of her media musings on Substack.

The Intermediality of the Cyanotype

By Alex Barnett

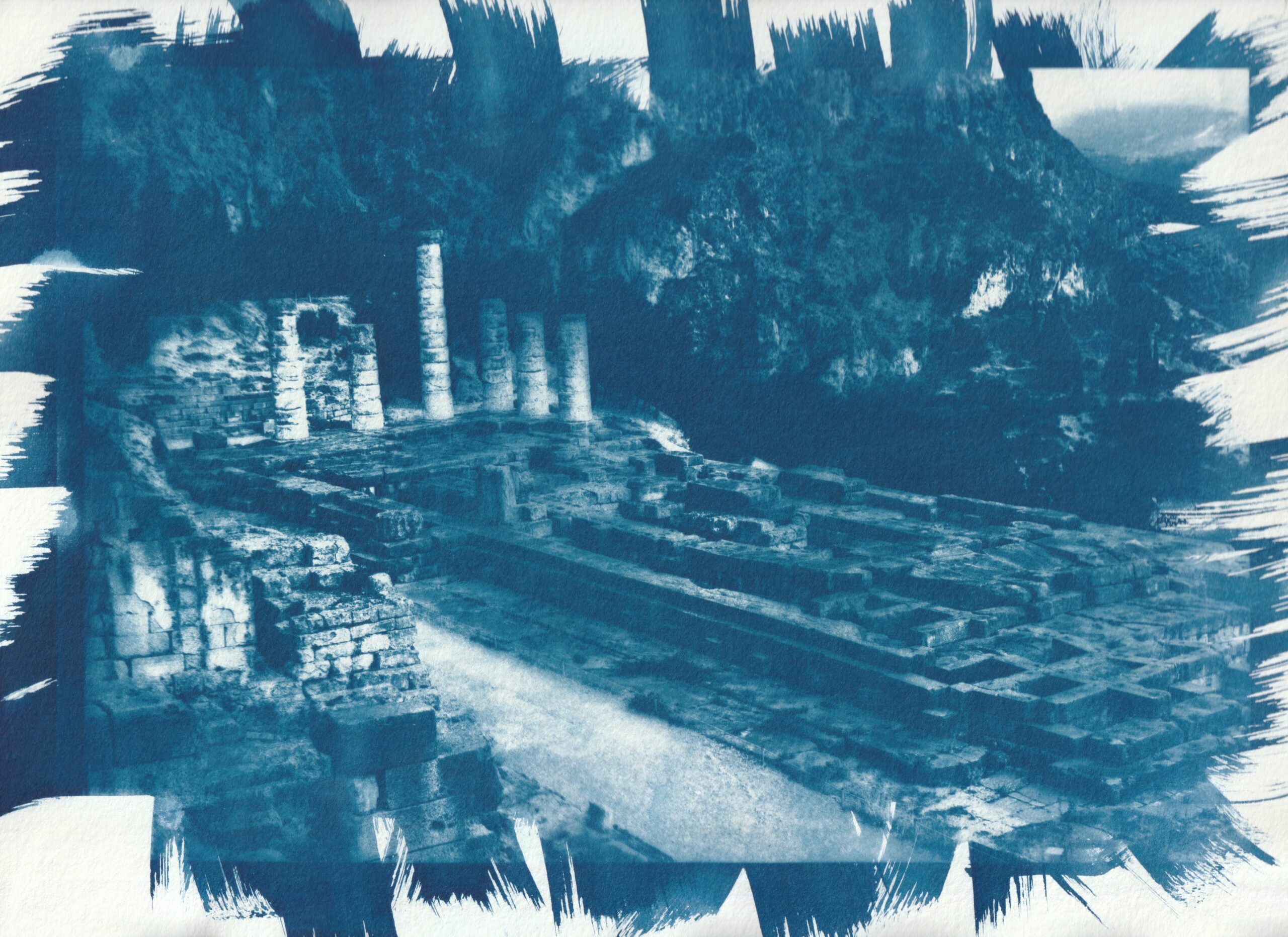

Figure 1: Cyanotype of Temple of Apollo in Delphi. Alex Barnett

Cyanotypes, or sunprints, are inexpensive, user-friendly pieces of analog contact photography that do not require film cameras, darkrooms or buckets of fixer to produce.

They tend to be most associated with photograms—images derived from the placement of small organic or inorganic objects (flowers, hands, yarn, etc.) atop a UV-sensitized surface, allowing the sun to uncover their undetectable transparencies. The cyanotypes I prefer to make choose extant photographs as their subject. I turn digital or digitized analog photographs into negatives with Photoshop, an Inkjet printer, and transparency film. I then place one or more negatives atop thick watercolor paper I’ve already painted with Cyanotype A & B, or Potassium ferricyanide and Ferric ammonium citrate, which allow the print to turn Prussian blue. The sun burns the image into the coated paper—a subsequent water bath (inside and away from sunlight) transforms the exposure from unreadable bronzy mush into monochromatic blue & white in a matter of seconds.

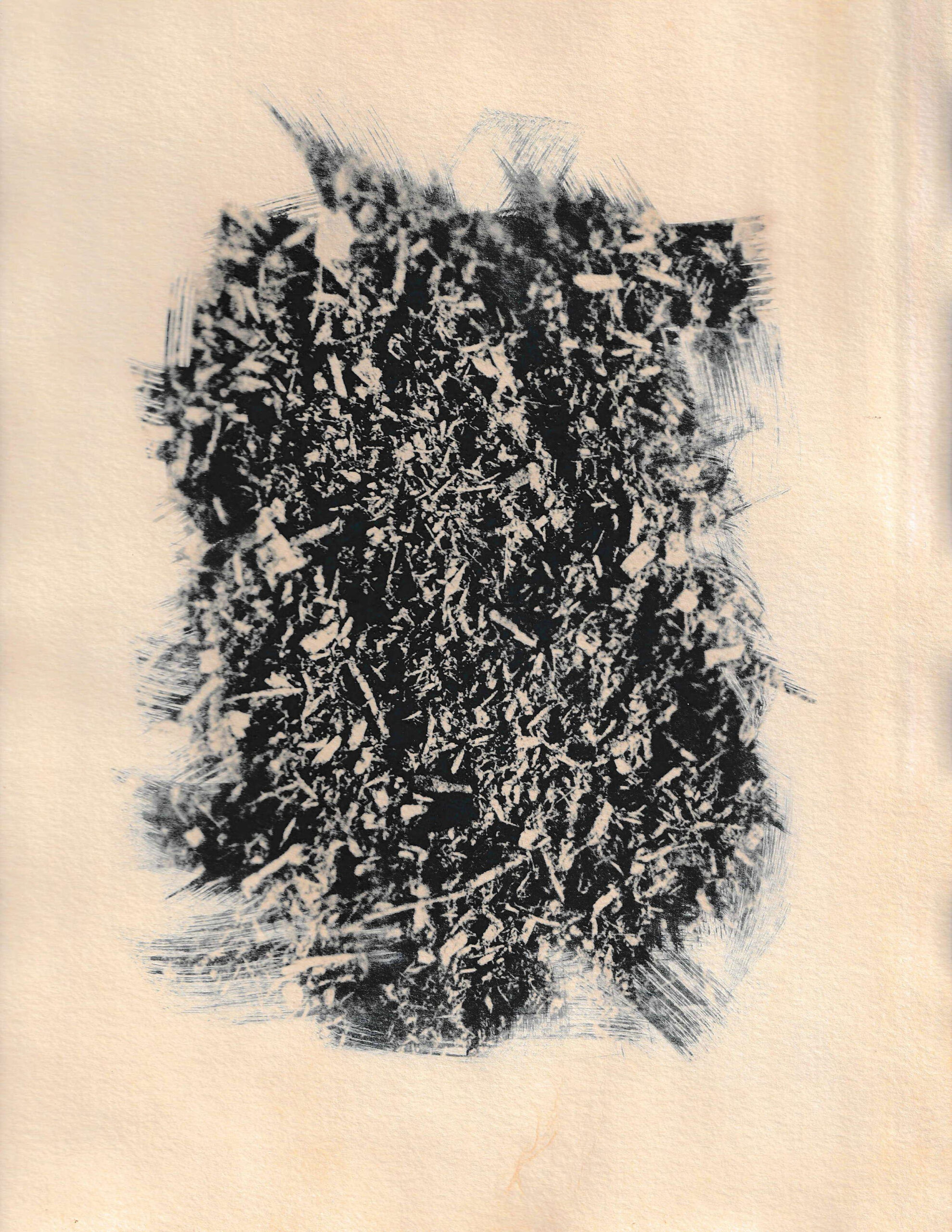

It is difficult to deviate from blue, but certain chemical reactions allow the print to shift between earthy, sandy, and inky primary shades of blue or brown—in one of the cyanotypes pictured here, I bleached the print after I washed it, and then bathed it again in breakfast tea. The bleach allowed tea tannins to interact with the developed chemicals on a molecular level to turn the image an inky almost-black & blue. The tea also stained the paper, now an odd and streaky beige.

Figure 2: Cyanotype of backyard mulch. Alex Barnett

Photograms, like other early photographic methods, might have been deemed “sun paintings,” while the more contemporary photos used for my favorite kind of cyanotypes would be “light writings.” These cyanotypes, therefore, are somewhere in between—sun paintings of light writings. Unless one has access to a UV lamp, every cyanotype of the same source image will differ because the sun acts as a highly volatile and variable light source. Minute changes in angle of sunlight, cloud cover, air pollution, application of chemicals, and duration of exposure affect the resulting image, usually in unpredictable ways. This is why I find cyanotypes intermedially fascinating. Infinitely reproducible digital photographs through this process become subject to analog chemical reactions and transform into unique material images. Like analog photographs, these unique artworks fade and blur when continuously exposed to (sun)light, but unlike analog photographs, they will regenerate to the period before UV-damage if stored in sunless conditions, like a basement. If I cyanotyped an image of another person, maybe my grandmother, I’ve created a near-immortal image of her—immortal as long as I preserve whatever paper or cloth or wood displays her image.

My cyanotypes, so far, have featured old digital photos from various iterations of my iPhone, photos of places like the Temple of Apollo in Delphi, or a field of mulch in my hometown. In one, the frame of the negative is obvious; in the other, invisible. The image that extends and disappears into the chemical brushstrokes possesses a certain obtuse drama (the mulch, in this case) because the negative is larger than the diameter of the painted frame, so the photographic referent breaks apart into bristles. I prefer the messier alternative, in which the rectangular dimensions of the negative stamp the image into the disordered frame of empty blue streaks. I read the image as an artifact of traditional photographic framing having been repurposed by the sunprinting process. The photographic frame becomes haphazard and irrational, the chemical frame motivated and reasonable, a way to restructure my ten-year-old memory of an ancient place captured by an obsolete smartphone printed onto flimsy paper coated by unkillable chemicals that I can only look at if I keep out of sight.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Alex Barnett is a graduate student in Intermediality Studies at the University of Edinburgh. He holds a B.A. in Radio/TV/Film and Creative Writing from Northwestern University. His research and creative interests include phototextuality, slow cinema, and interactive media.