The Rise and Fall of the Dinosaurs

In a departure from the norm, Dr. Steve Brusatte from the Edinburgh University School of Geosciences came to the IGMM to tell the tale of the dinosaurs. Steve guided us through their tumultuous evolution, from their rough start in the early Triassic culminating with total world domination in the Cretaceous period. He spoke with the excitement and passion of every dinosaur fan but the authority and expertise of someone who is a true leader in their field. The following is a whirlwind tour of the rise and fall of the dinosaurs.

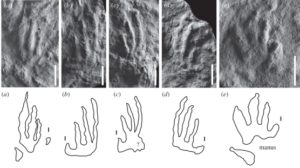

Their story begins in the Triassic period, around 250 million years ago. At this point in time dinosaurs were few and far between, and the majority of those that were roaming the ancient super continent of Pangea were about the size of a domestic cat. These early dinosaurs lived in the shadow (quite literally) of the crocodile-line archosaurs. Whilst modern day crocodiles are hardly teddy bears, these ancient crocs were truly monstrous, with some reaching the size of a bus. We know this due to some excellent trace fossils found in Poland; trace fossils being the fossilised marks left behind by dinosaurs, such as footprints. These show that one of the earliest ancestors of the dinosaurs, a dinosauromorph called Prorotodactylus, was small, walked on all fours but was also rare as Steve estimated that only ~5% of the footprints belonged to Prorotodactylus (Brusatte, Niedźwiedzki & Butler, 2010), see figure 1. However, the supercontinent of Pangea was breaking up. With this continental divorce came mega volcanoes, causing a mass extinction that wiped out most of the crocodile-line archosaurs. The planet was ripe for the taking, and the dinosaurs were there to do it.

Figure 1: a-e all show examples of Prorotodactylus footprints found in rock from the early Triassic in Poland. Scale bars are 1cm. Adapted from Brusatte, Niedźwiedzki & Butler, 2010.

The Jurassic period is when dinosaurs really hit their stride. They exploded in diversity and conquered the globe. One such place that these dinosaurs called home was our very own Scotland. During a trip to the Isle of Skye, Steve and his team noticed a series of huge holes in the rock. On closer inspection, these holes followed a left-right-left-right pattern. Taking a step back he realised what they had found; it was the fossilised remains of an ancient dinosaur highway (dePolo et al., 2018), see figure 2. These tracks belonged to sauropods, those massive long-necked plant-eaters that would have towered over houses and weighed several tonnes. The transition from the Jurassic to the Cretaceous was much less dramatic than the mass extinction that marked the end of the Triassic period, and with this transition the real monsters appeared…

Figure 2: A striking example of one of the footprints found on the Isle of Skye. The indents of the toes can be clearly seen, and it even appears that this sauropod had fleshy pads on the bottom of its feet. Adapted from dePolo et al, 2018.

Tyrannosaurs weren’t always the gargantuan killing machines that the movies would have us believe. They, much like dinosaurs themselves, have rather humble beginnings. The oldest Tyrannosaur fossils originate from China and looked quite different to the tyrant king that we know and love. One of these early Tyrannosaurs, Guanlong, was small and no doubt a fierce predator, but it was hardly nightmare fuel (Xu et al., 2006). In the middle Cretaceous the fossil record is poor, and on the other side of this fossil anomaly we have the huge Tyrannosaurs in all their glory. Steve described to us one intermediate Tyrannosaur that seems to fill this gap, called Timurlengia. About the size of a horse, it was still a long way off the 7-tonne beast of T. rex, but it does shed light on how they may have become the dominant predator in the late Cretaceous. Using CAT scans to measure the size of its brain, Steve found that it had a remarkably large brain relative to its size, along with an elongated cochlea (Brusatte et al., 2016), see figure 3. This potent package of brain and brawn would have made Timurlengia a fierce predator. It is thus not hard to imagine how such an animal was able to flourish, evolve and eventually give rise to the huge Tyrannosaurs.

Figure 3: This shows the braincase for Timurlengia which has been constructed using CAT scan data. The elongated cochlear duct can be seen in pink. This would have enabled it to better hear low frequency sounds. Adapted from Brusatte et al., 2016.

Dinosaurs are survived in the modern day by birds; that is to say that birds ARE dinosaurs. Incredible new fossils document the evolution of birds from dinosaurs. One such example is the exquisite skeleton of a dinosaur named Zhenyuanlong. Inspection of the skeleton shows that it was undoubtedly a dinosaur, but it also has characteristics which we now know are definitively avian (Lü & Brusatte, 2015), see figure 4.

Figure 4: The incredibly well-preserved skeleton of Zhenyuanlong. The lighter brown halo surrounding the skeleton is the feathers. Note the distinct wing-like arm in the foreground; it looks very similar in structure to the wings of modern birds! Taken from Lü & Brusatte, 2015.

It is just one of many fossils which have preserved not only the skeleton but also the feathers, that most avian of features. Some fossils have even preserved the pigmented melanosomes of the feathers, and it seems that these dinosaurs would have had colourful plumage (Zhang et al, 2010). However, things were about to dramatically change for the dinosaurs and these primitive birds. Earth would never be the same again.

A huge asteroid, 6 miles across, smashed into the Earth with the energy equivalent to millions of nuclear bombs. The results were truly apocalyptic: volcanoes erupted throughout the world, earthquakes rippled through the Earth’s crust as if it was jelly, blazing infernos decimated the plant life, the dust and smoke would have blotted out the sun leading to almost permanent darkness and a nuclear winter lasting several years. Mammals and birds made it through this onslaught and inherited the kingdom that was once the dinosaurs. That is not to say that ALL mammals and birds survived, many of their species would also have been wiped out too. Mammals became the new dominant force of this battered and scarred Earth, and the rest as they say, is history.

Steve managed to cram this action-packed story into just one hour, presenting some incredible fossils and data to support it along the way. He also noted that throughout the dinosaur’s dynasty there were smaller, less dramatic extinctions that were likely due to changing climate and sea levels. Looking at the geological and fossil records, these indicate that the changes occurred at a much slower rate than what we are experiencing right now. Steve ended on a poignant note: if it happened to them, what’s to stop it happening to us?

The dinosaur family tree. Those highlighted in red perished during the end Cretaceous extinction, and those in green survived. The evolution of key bird-like features are marked. It also suggests that perhaps birds adopted a seed-based diet prior to the extinction, maybe this is what gave them an edge? This is for the next generation of palaeontologists to discover. Taken from Brusatte, 2016.

References and suggested reading:

Brusatte, S. (2018). The rise and fall of the dinosaurs (1st ed). London, England: Pan MacMillan.

Brusatte, S. L. (2016, May 23). Evolution: How some birds survived when all other dinosaurs died. Current Biology, Vol. 26, pp. R415–R417.

Brusatte, S. L., Averianov, A., Sues, H. D., Muir, A., & Butler, I. B. (2016). New tyrannosaur from the mid-Cretaceous of Uzbekistan clarifies evolution of giant body sizes and advanced senses in tyrant dinosaurs. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 113(13), 3447–3452.

Brusatte, S. L., Niedźwiedzki, G., & Butler, R. J. (2011). Footprints pull origin and diversification of dinosaur stem lineage deep into Early Triassic. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 278(1708), 1107–1113.

dePolo, P. E., Brusatte, S. L., Challands, T. J., Foffa, D., Ross, D. A., Wilkinson, M., & Yi, H. Y. (2018). A sauropod-dominated tracksite from rubha nam brathairean (brothers’ point), Isle of Skye, Scotland. Scottish Journal of Geology, 54(1), 1–12.

Lü, J., & Brusatte, S. L. (2015). A large, short-armed, winged dromaeosaurid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Early Cretaceous of China and its implications for feather evolution. Scientific Reports, 5.

Xu, X., Clark, J. M., Forster, C. A., Norell, M. A., Erickson, G. M., Eberth, D. A., … Zhao, Q. (2006). A basal tyrannosauroid dinosaur from the Late Jurassic of China. Nature, 439(7077), 715–718.

Zhang, F., Kearns, S. L., Orr, P. J., Benton, M. J., Zhou, Z., Johnson, D., … Wang, X. (2010). Fossilized melanosomes and the colour of Cretaceous dinosaurs and birds. Nature, 463(7284), 1075–1078.