While leafing through the archives in search of new materials for this blog, it becomes impossible not to think of those who made it their job to research the wealth of information and knowledge hidden in archival materials and analyse it so as to give voice to the big issues and public debates of times past. With that in mind, then, the spotlight today is on the stories of two equally brilliant social historians, one a former staff member and one a prestigious alumna of the University of Edinburgh:

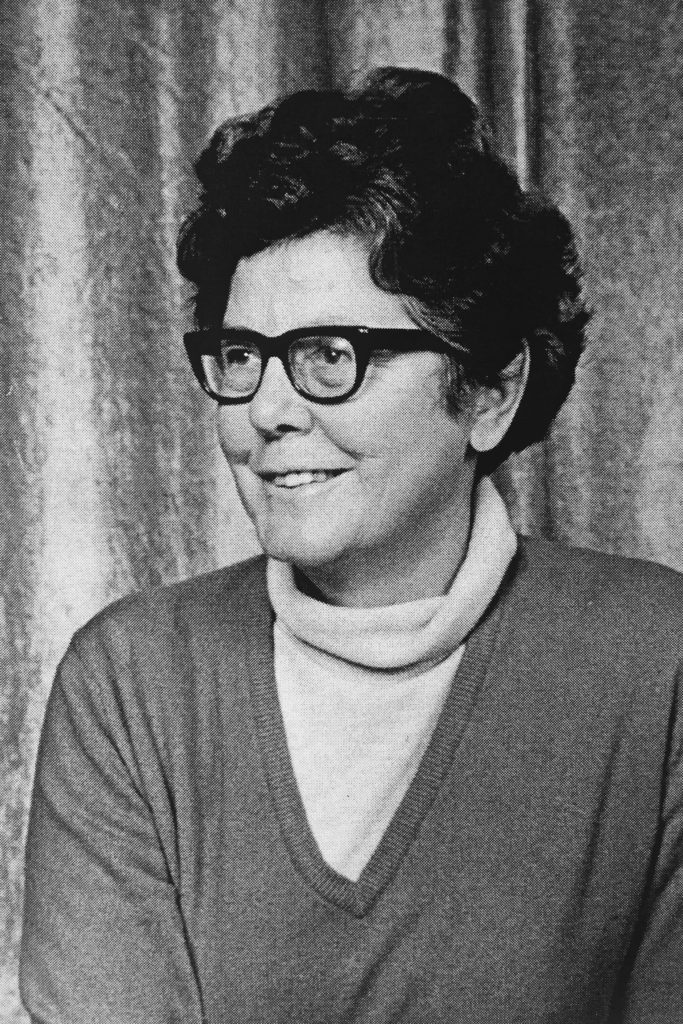

Dr Rosalind Mary Mitchison

In 1942 Dr Rosalind Mary Mitchison, known to friends and family as ‘Rowy,’ graduated from the University of Oxford with a First Class Degree in Mathematics and History. An excellent student with a distinct inclination for academic work, between the years 1943 and 1946 Dr Mitchison worked as an Assistant Lecturer at the faculty of History of the University of Manchester, before moving to Edinburgh with her equally academic husband to take up a post as Assistant Lecturer in the History Department at the University of Edinburgh.

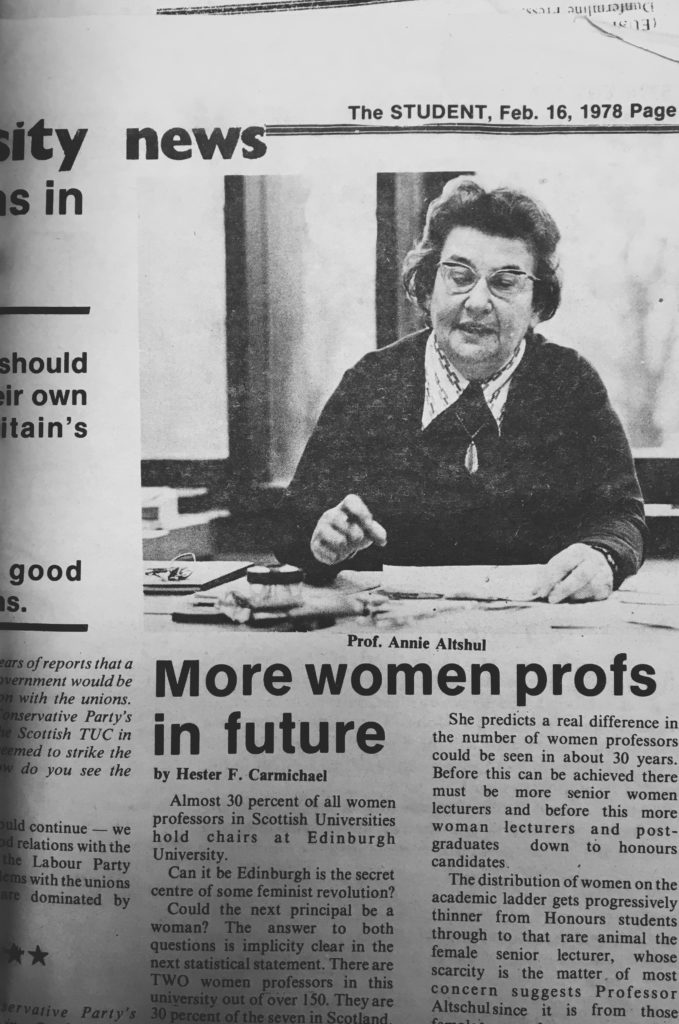

Marked by numerous part-time appointments and several breaks dictated by the necessity of looking after her children and family, Dr Mitchison’s early career was certainly not an easy one. Yet, as one colleague remarked in her Memorial –collated by her husband–, if Dr Mitchison ‘did not find the University’s male-dominated ethos very welcoming to a woman who interleaved her teaching commitments with having babies,’ she remained ‘unlikely to be intimidated’ by such injustices, and continued pursuing her research.

In 1967, with her children grown to a more manageable age and the help of a part-time housekeeper, Dr Mitchison was finally able to take up a full-time employment at the University of Edinburgh, where she first covered the post of Lecturer, being soon promoted to Reader and, eventually, coming to hold the title of Professor. She was, by all accounts, ‘a great teacher’:

Exacting, kindly, never letting anyone get away with their second best. Always on top of her subject.

She was also, despite never calling herself so, a feminist, or so she was described by her former colleague R. J. Morris in an obituary published by The Guardian:

I never heard Rowy use what we would now call feminist language, but she had many qualities and ambitions that a later generation of women will recognise. […] At work, she took care to make spaces for other women academics, and occasionally pointed out to colleagues that women faced a variety of pressures.

A passionate academic, Dr Russel Moller officially retired in 1986, though she continued to follow her research interests and remained actively involved in the university community. In 1992, she received an Honorary Doctorate from the University of St. Andrews, and she was elected to the Royal Society of Edinburgh in 1994. In 2000, Dr Mitchison published her lifetime work under the title of The Old Poor Law in Scotland: The Experience of Poverty, 1574 – 1845 (Edinburgh University Press). The book, a culmination of a career-spanning interest, was labelled as ‘splendid’ by many a reviewer, and considered a great contribution to the field of Social History.

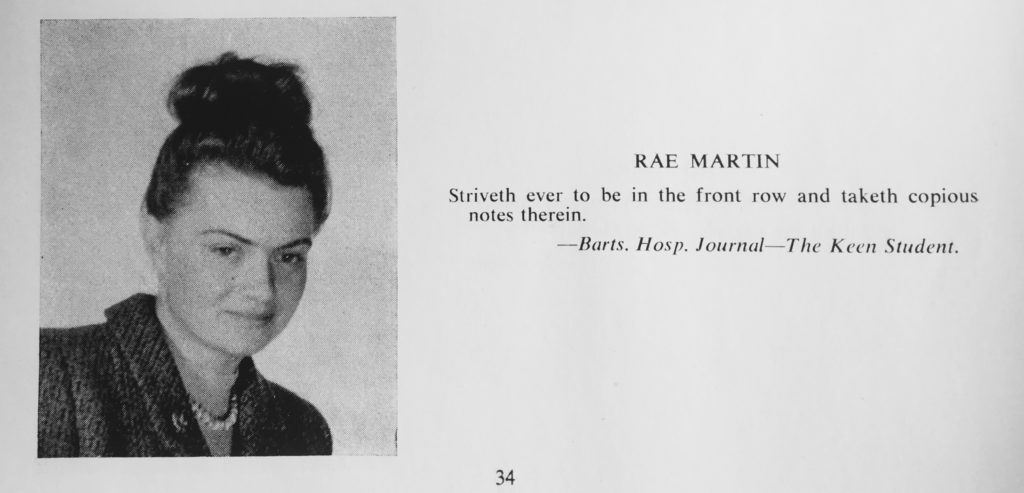

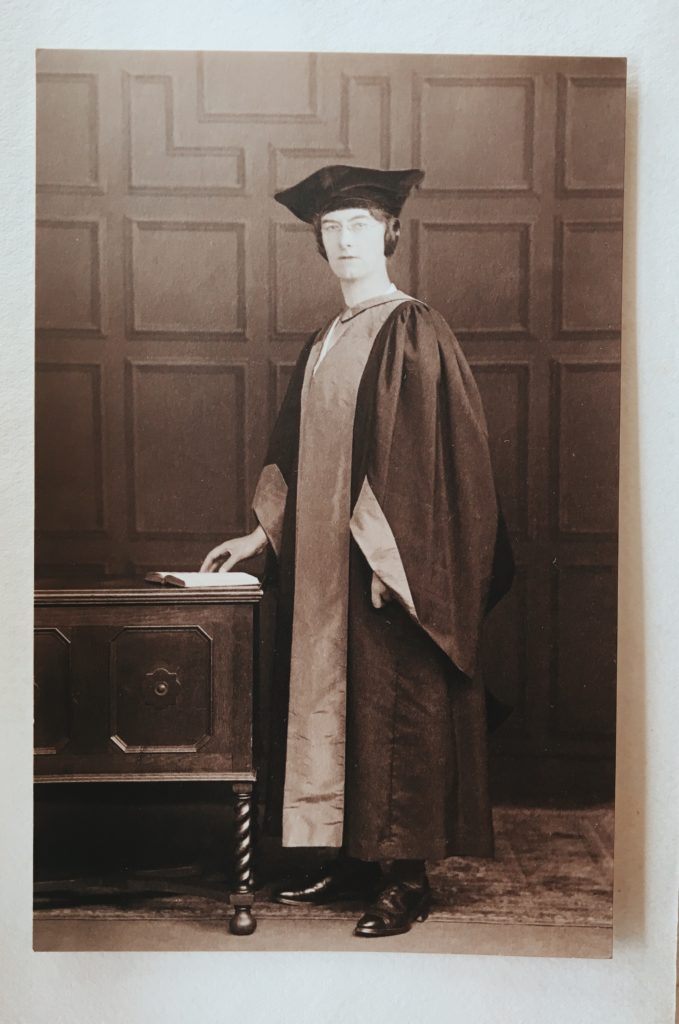

Dr Asta Winifer Russel Moller

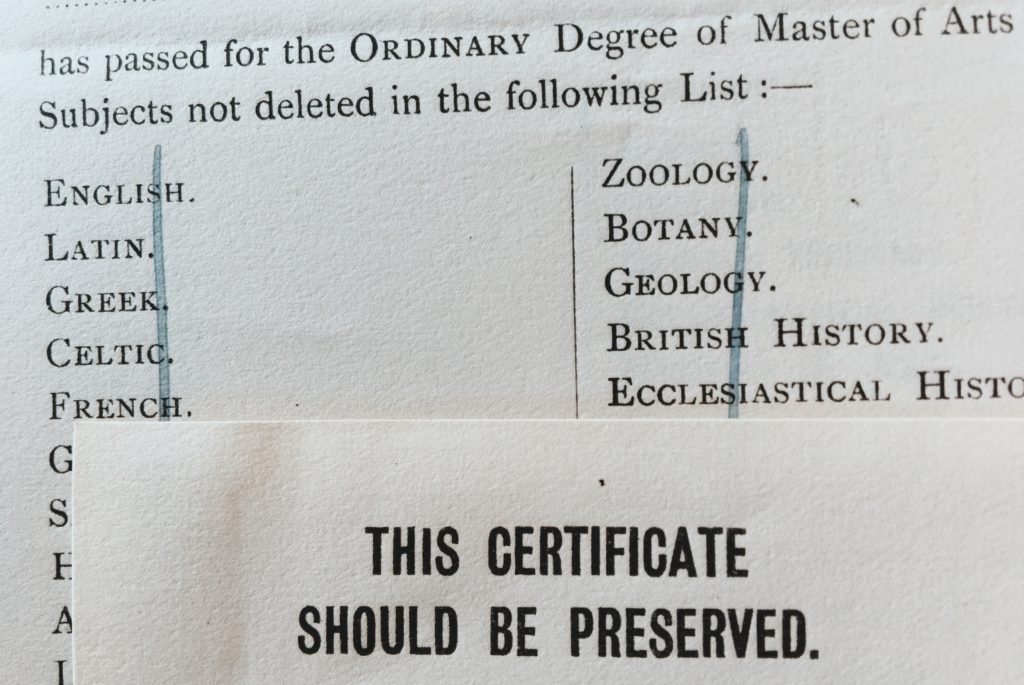

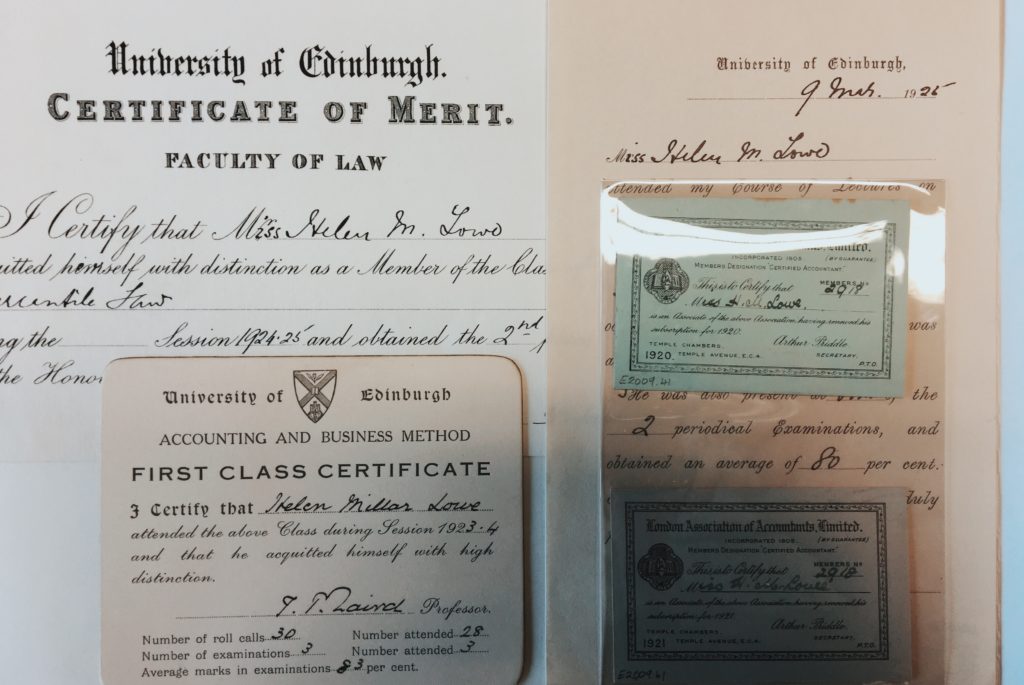

Between 1916 and 1920, Dr Asta Winifer Russel Moller attended the University of Edinburgh, where she pursued her undergraduate degree by attending classes in English. Moral Philosophy, British History, Political Economy, Economic History and Political Science. During her time at Edinburgh, Dr Russel Moller took part in numerous extra-curricular activities, and took up residence in Masson Hall, where she proved keen to forge connections with her fellow female students.

A dedicated and brilliant scholar, Dr Russel Moller graduated from the University of Edinburgh on 8th July 1920 with a Second Class Honours Degree in Economic Science, and later moved on to attend Somerville College, Oxford, where she began a one-year post-graduate degree programme in Social History.

Graduating again in 1921 with a Bachelor of Letters on the subject of English Coal Mining in the 17th Century, Dr Russel Moller impressed her supervisors at the University of Oxford, who were keen to praise ‘her knowledge of the history of Industry’ and who repeatedly claimed ‘it has been a great advantage to have in the College an advanced student of her ability and keen interest in economic and social questions.’

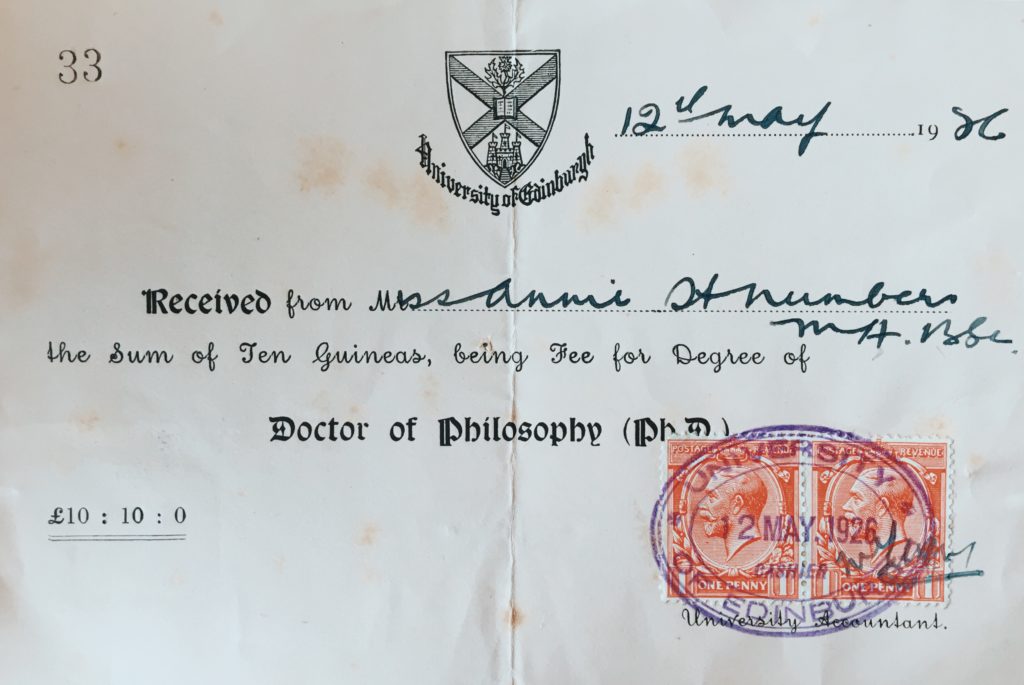

Between 1921 and 1926, Dr Russel Moller applied for a number of academic posts, among which those of Lecturer in Economics at King’s College for Women, London, and of Warden of Crosby Hall. Then, in 1926, Dr Russel Moller returned to Oxford, joining New College to pursue a DPhil on the history of coal mining. As a scholar who ‘des not spare herself pains’ and whose ‘judgement is sound,’ Dr Russel Moller was considered a great asset for the University, with her supervisor claiming that any ‘institution which secures her services would find her influence steadily growing’ thanks to the ‘thoroughness, originality and vivacity’ or her research work.

She has exhibited in a marked degree of capacity for sustained hard work, and she has not shrunk from work of which some has been necessarily laborious and detailed in character.

In 1933, seven years after the start of her research project, Dr Russel Moller was awarded her DPhil for the thesis ‘The History of English Coal Mining, 1500-1700,’ a seminal work and still a significant reference for scholars in the field.