By Luisa Gillies

Describing the Female

There is a lot to be learned by exploring the instances in which women are mentioned in the documents of the Medical History of British India. For example, the words ‘man’ and ‘men’ appear more than three times more frequently than ‘woman’ and ‘women’. This simple fact is revealing with regard to the focus of the documents – they seem to center on men more than on women.

However, searching for ‘women’ in the documents does not reveal the full story: it leaves out those who are described in other ways. What can we learn from how different women are described as ‘girls’, ‘women’ and ‘ladies’?

I searched for each of these terms in the documents (in both their singular and plural forms1) to figure out which ones appear the most. I found that: ‘woman’ and ‘women’ take the lead, with a combined total of 5,053 appearances; then ‘lady’ and ‘ladies’, with 602; and finally ‘girl(s)’, with 304. We can now have a look at each in more depth.

Girls

Scholars have found that it is much more likely for adult women to be referred to as ‘girls’ than it is for adult men to be referred to as ‘boys’ (Sigley and Holmes 139). I decided to find out whether this is the case in our documents.

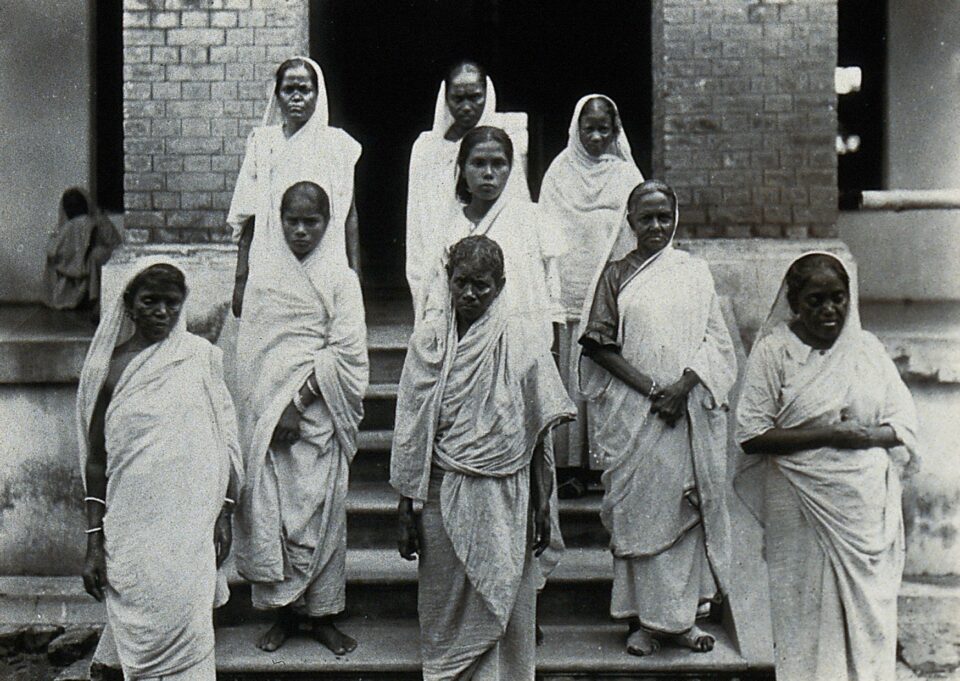

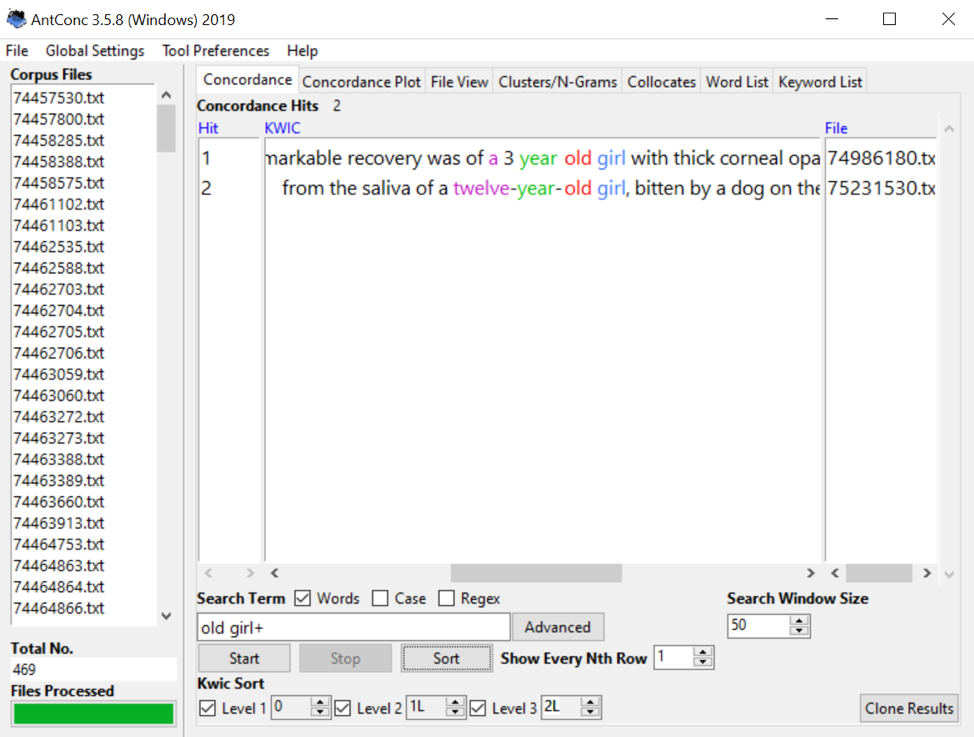

I searched for ‘girl(s) aged’, ‘girl(s) of’, and ‘old girl(s)’. This allowed me to find a total of 31 points in which the term ‘girl’ is used to describe females of explicitly mentioned ages (for example, ‘a 3 year old girl’ and ‘a twelve year-old girl’ in Figure 1). Then, I looked through all of these points, taking note of the exact ages mentioned. The highest was 25.

Figure 1. Screenshot of AntConc search for ‘old girl(s)’.

I then did the same for ‘boy(s)’, and found a total of 61 appearances. That this number is much greater than the other is unsurprising, since the documents talk about men much more than they talk about women. I found that the maximum age referred to for boys was 18 – seven years younger than the one for girls.

A problem here is that this investigation leaves out all the points in which ‘girls’ and ‘boys’ are mentioned without making the age explicit. However, this is still a significant finding. It suggests that, in the documents, ‘girls’ is used to describe older people than ‘boys’ is.

Because ‘girls’ and ‘boys’ are terms associated with youth, calling adult women ‘girls’ suggests that they are more immature than their male counterparts. This hypothesis would reflect the gendered perspective of the 19th and 20th centuries.

Ladies

One of the most frequent words associated with ‘lady’ and ‘ladies’ is ‘doctor’, most commonly in the form of ‘lady doctor’ – this appears 85 times. ‘Male doctor’, on the other hand, appears only once. This is a striking difference.

It is very unlikely, however, that there were 85 times more female than male doctors in British India. Much more likely is that doctors were usually assumed to be male, and that therefore male doctors were simply referred to as ‘doctors’, rather than as ‘male doctors’. More information about female doctors in British India can be found here.

Interestingly, neither ‘woman doctor’ nor ‘women doctors’ appear even once (and ‘female doctor(s)’ appears only 19 times). So, while ‘lady’ is a relatively unpopular term in the documents as a whole, it is significantly preferred in the particular context of describing female doctors.

As Sigley and Holmes (140, 150) point out, the term ‘lady’ has patronizing, ‘pseudo-polite’ connotations. It is possible, then, that female doctors were generally treated in a condescending way, and that this extended to their descriptions in the documents.

Women

In the documents, the word most associated with ‘woman’ and ‘women’2 is ‘unlicensed’, followed by ‘registered’. I found that this is due to a significant number of mentions of ‘unlicensed women’, ‘unlicensed woman’, ‘registered women’ and ‘registered woman’ – 338 in total.

The British government was interested in regulating sex work to prevent the spread of diseases amongst soldiers (Millard and Quinn), and this is why we find the terms ‘registered’ and ‘unlicensed’: they refer to sex workers. You can find out more about the treatment of sex workers here and here.

There are no mentions of ‘registered’ or ‘unlicensed’ ‘ladies’ or ‘girls’: it seems that sex workers were only referred to as ‘women’ (other than as ‘prostitutes’), with the exception being only one mention of ‘registered female’.

Why does all this matter?

It is important to remember that all of these different terms used to describe women are English terms. Not all languages would use the same word to describe an adult woman as the one used to describe a child; and not all languages would refer to female doctors and female sex workers with two completely different words.

Nonetheless, these findings reveal some interesting ways in which English-speaking (mostly British) writers thought of and described women. They did not see all women as ‘women’: sex workers were described as ‘women’, but doctors were ‘ladies’. And women were certainly not viewed or described in the same way men were: men seem to have been given much more attention, and considered more mature than women.

It is important to remember, of course, that the words in these documents were mostly written by men: it would be interesting to explore how differently women are described in contemporary documents written by women.

Works Cited

1In AntConc, the ‘?’ symbol denotes any one character, the ‘+’ denotes zero or one character, and ‘|’ denotes ‘or’. These symbols allowed me to search for singular and plural forms of each word at the same time. For example: ‘wom?n’ found results for ‘woman’ and ‘women’; ‘girl+’ found results for ‘girl’ and ‘girls’; ‘lady|ladies’ found results for ‘lady’ and ‘ladies’. Some OCR errors were found, but these did not significantly impact my research.

2(at a statistically unexpected rate)