By Héléna Lagreou

The Contagious Diseases Acts (CDA) are a series of British laws voted in 1864 and then later modified (Tambe 1-3). They were destined to fight against venereal diseases in garrisons’ cities and then extended to a wider territory. Yet, it was mostly a controltool over sex workers, by forcing morals from the British Imperial system hiding behind medicine (Tambe 5). These acts manifest themselves through regular and intrusive examinations of sex workers. If infected, the individuals were to be locked up, whereas clients were never put under any test or surveillance. Such clients were mostly soldiers representing the British Empire. Thus, this result shows a clear unbalance in treatment (Tambe 4-6).

Research terms,

Therefore, I want to fully investigate this subject, as the digitised files of the Medical History of British India, held at the National Library of Scotland seemed to be the perfect platform for it. Indeed, since the documents collected range from the 19th to the 20th century they would be in the centre of this controversial law. Thus, I focus my research on the term “prostitution” rather than “prostitutes”.

As I want to gain information on the perception of the enforcement of the law, I do not research individuals but to its concept. When searching the term “prostitution” I find 288 appearances. Yet, a distinct characteristic of this term jumps out, as it is almost always introduced by a qualifier, usually an adjective.

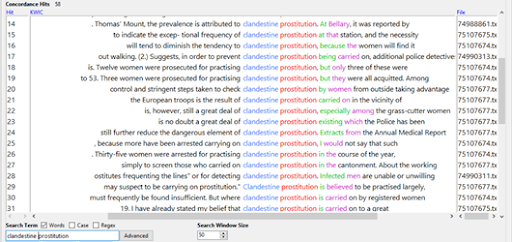

Three of them stand out, “clandestine” with 58 appearances, “illicit” with 48 appearances and “unlicensed” with 38 appearances. I was not expecting such terminology to describe sex work, as there is no qualifier next to the word referring to morals directly. Instead, it is mostly legal terms. But legal language is misleading on purpose. Indeed, in the 19th century, the British colonial power was questioned with the Revolt of 1857 (Naidis 793). The response of colonial power was the construction of a tight strong legal system to restrict and contain any agitation. Countless laws were developed such as the CDA. Indeed, by declaring cases of sex working as illegal it was easier to enforce the CDA.

“Clandestine prostitution”: the hidden fear,

The term “Clandestine prostitution” is the most used qualifier in this corpus. In terms of definition, it differs from the other two words “illicit” and “unlicensed” in the sense that it adds a moral connotation. Indeed, “Clandestine” implies besides an illicit practice, a hidden practice. The connotation of secrecy regarding sex workers and the definition of their work further its precariousness.

Above being illegal and condemning the practice itself, the confidential nature of it renders the workers invisible and their needs by furthering the illicit nature of the practice. Indeed, whenever practices are declared as “clandestine” every statistical research is brought down by simply stating that it is impossible to see it or understand it based on a supposedly covert system.

Whereas all indications seem to show that the practices were not hidden. In the corpus the term “clandestine” plays on the masked connotation to justify strong or aggressive actions. When I observe the context and the verbs used, it frequently refers to an unknown mass of sex workers. The term clandestine is therefore used to refer to a hidden high quantity of illicit practices. Presenting “prostitution” is that regard enforces a paranoia around it. Hiding behind a false clandestine nature, it allows to create a delusion around the extent of sex work. This psychosis pushed to enforce stronger measures. Therefore, the term is used more to justify the strong laws rather than define anything.

Figure 1: Research results for “clandestine prostitution”.

“Illicit prostitution”: false legal pity,

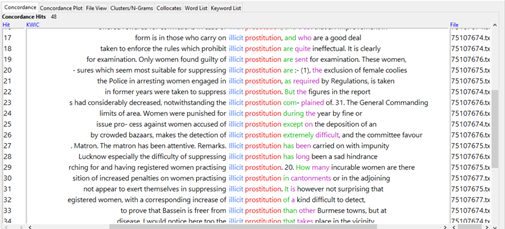

Conversely the qualifier “illicit” to define “prostitution” as something that is attested. Therefore, around this qualifier of prostitution the language is vastly different. Words surrounding this qualifier refer to prohibition, suppression, and detection. Interestingly, by defining sex work as “illicit” the textual references most frequently give an underlying pity to the sex workers themselves.

Figure 2: Research results for “illicit prostitution”.

Therefore, the individuals conducting sex work are here presented more as victims of a system rather than criminals. This complete opposition with the term clandestine informs us how these qualifiers of sex work only justify intrusive and unjust law-making. As a matter of fact, inversely to “clandestine production”, the sex workers are now presented as if law is protecting them and others from harm.

Even if the language is maintained around punishment, the individuals conducting sex work are named as a group, mostly using the term “women”. But they are never referred as “prostitutes”, but only as “women practicing prostitution”. This distancing of the practice presents a passivity or a necessity to carry out sex work.

How sex work is qualified within a text gives us, with context, how it is perceived and manipulated (hyperlink Frederike’s text). Indeed, the term “prostitution” cannot be studied out of its power context. Here, sex work when qualified is used to further justify the unfair and intrusive rules enforced in British India throughout the 19th to the 20th century. But the reality of sex and punishment in British India was the extreme conditions of confinement for convicted sex workers were extremely deficient (Legg 1459).

Works Cited

Legg, Stephen. “Stimulation, Segregation and Scandal: Geographies of Prostitution Regulation in British India, between Registration (1888) and Suppression (1923) ; Rereading the 1890s: Venereal Disease as 'Constitutional Crisis' in Britain and British India; Sexually Transmitted Diseases and the Raj; Looting the Lock Hospital in Colonial Madras; Governing Prostitution in Colonial Delhi: from Cantonment Regulations to International Hygiene (1864-1939); Of Scales, Networks and Assemblages: the League of Nations a.” Modern Asian Studies, vol. 46, no. 6, 2012, p. 1459.

Naidis, Mark. “The Aftermath of Revolt: India, 1857-1870.” Vol. 70, no. 3, 1965, p. 793.

Tambe, Ashwini. “The Colonial State, Law and Sexuality”. Codes of Misconduct. NED - New ed., University of Minnesota Press, 2009, pp. 1-25.