By Friederike Gerken

This article discusses the portrayal of sex workers in reports on lock hospitals in British India. Lock hospitals were established as part of the Contagious Diseases Acts in an attempt to tackle the spread of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) within the British military. They were medical institutions that quite literally locked away sex workers who were diagnosed with STIs, in particular syphilis and gonorrhoea. These illnesses were rampant within the military and the sex workers the soldiers frequented were considered the culprits whose profession therefore had to be strictly regulated. This regulation was justified through dehumanisation and demonisation of sex workers which can be found in the rhetoric used in annual reports on lock hospitals.

Britain passed its first Contagious Diseases Act in 1864, with additions in 1866 and 1869. In 1868, occupied India passed its own version of the Act. These pieces of legislation required sex workers in cities of military significance to register with local authorities, to undergo fortnightly medical examinations, and to go to a lock hospital if they were found to have contracted an STI. Once admitted to a lock hospital, women were only allowed to leave again once they were declared cured. While soldiers were also admitted to these hospitals, I will mostly focus on the women patients as it is they who were considered at fault for spreading disease.

Searching the documents for words that appear alongside ‘prostitute(s)’ and ‘prostitution’, some adjectives appear at a remarkably high rate, the majority of which are of an administrative nature. If a sex worker is not ‘registered’ or ‘licensed’, descriptions range from the more descriptive ‘unregistered’ and ‘unlicensed’ to words with stronger value judgements, such as ‘clandestine’ and ‘illicit’. These strong oppositions illustrate that while the colonial government recognised that it cannot eradicate sex work altogether, the rules created by the Contagious Diseases Act were by no means a move towards recognising the humanity of sex workers. On the contrary, any sex work happening outside of the government’s approved framework was criminalised, which is further emphasised by numerous mentions of ‘fines levied’ on unregistered women. Many of the documents agree that most STIs are spread when soldiers buy the services of unlicensed sex workers. In this context, numerous notes written by military officials describe unlicensed sex work as the ‘evil’ that cannot be controlled.

Male soldiers who contracted STIs and were admitted to lock hospitals are treated more humanely by the reports. The documents state whether they are young or old, British, European, or Indian, but never use any language of legality or morality to describe them. (For more about how the colonial government forced sex workers into a harsh legal system see here). This disparity between who is and who is not judged is further emphasised by the material structure of the reports themselves.

The archive contains annual reports on lock hospitals from five administrative regions: British Burma, Central Provinces, North-Western Provinces and Oudh, the Madras Presidency, and Punjab*. These reports summarise data on each region’s lock hospitals in a given year, ranging from numbers of women admitted and diseases that were diagnosed, as well as financial matters. Collected to form one whole, they were printed and bound by each province’s government press and in some cases addressed to specific members of the military or the government. This process of constant surveillance and documentation of STI cases in sex workers showcases that the Contagious Diseases Acts were a large bureaucratic addition to the colonial government (Stockstill 24).

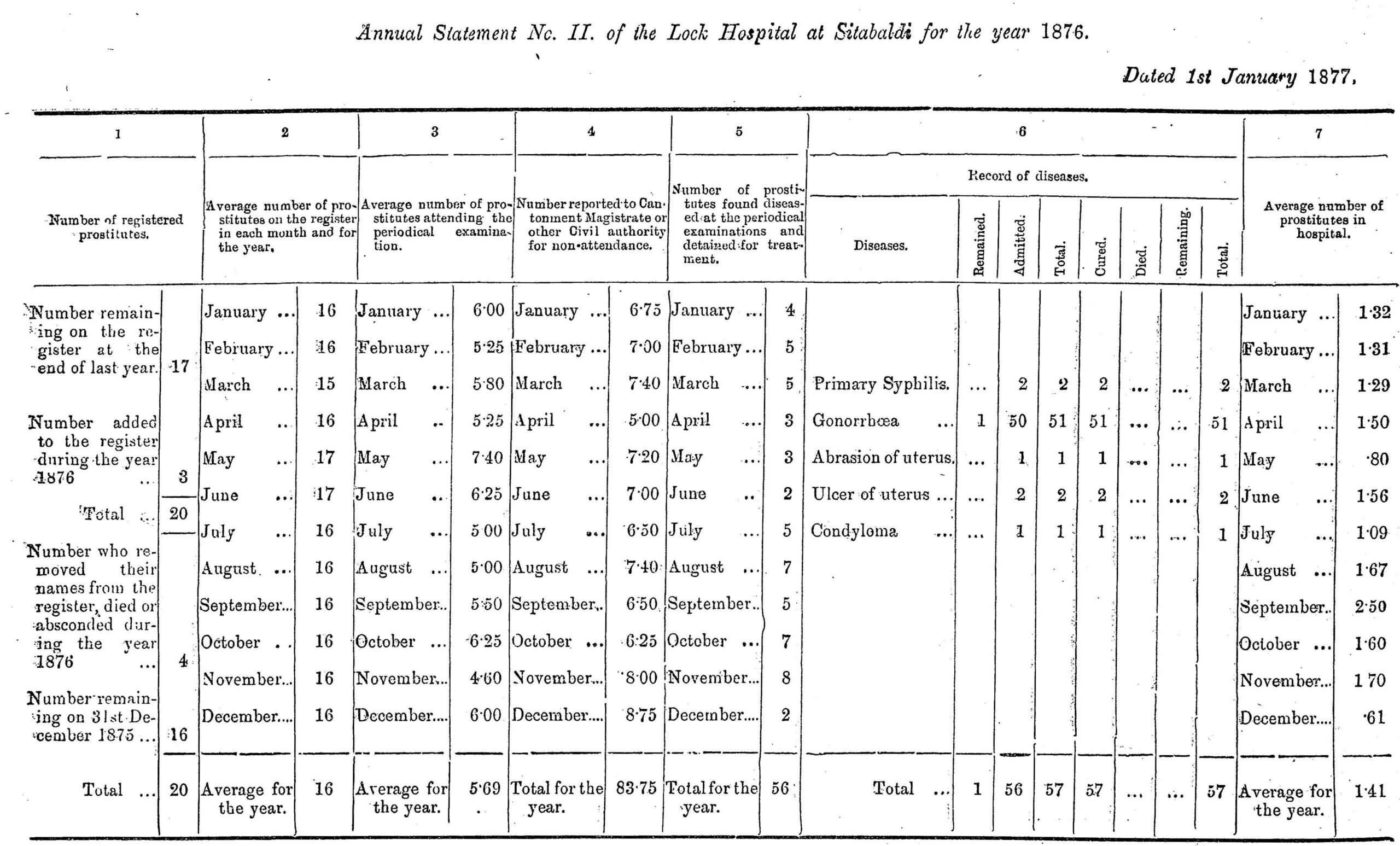

Figure 1 - One of many data tables in the annual reports. Source: https://digital.nls.uk/indiapapers/browse/archive/75109445

These standardised data tables which list the comings and goings of about one hundred women per year at each hospital show the systematic, bureaucratic side of the lock hospitals. Highly complex health issues of individuals spread over a large geographic area are turned into numbers, allowing for easy comparison between hospitals as well as across time.

In the reports, these data tables are surrounded by notes from doctors working in the hospitals and high-ranking officers, contextualising the numbers listed. However, nowhere in the documents do we see any trace of the hospitalised women. Besides a handful of ethnicities that are named at a rate so small it makes them irrelevant for this analysis, there is virtually no personal information about the sex workers included in these reports. The only purpose of the Contagious Diseases Act was to reduce STIs in the military (Mishra 559), so to authorities, the women discussed in these documents are but a potential threat to the health of British soldiers. Further, the reports demonise unlicensed sex workers who were associated with being the largest spreader of STIs and are represented as dangerous temptresses. This applies even when the documents recognise that a lot of women are driven to (unregistered) sex work by extreme poverty. Here, it also becomes apparent how the system attempts to justify itself using somewhat circular reasoning.

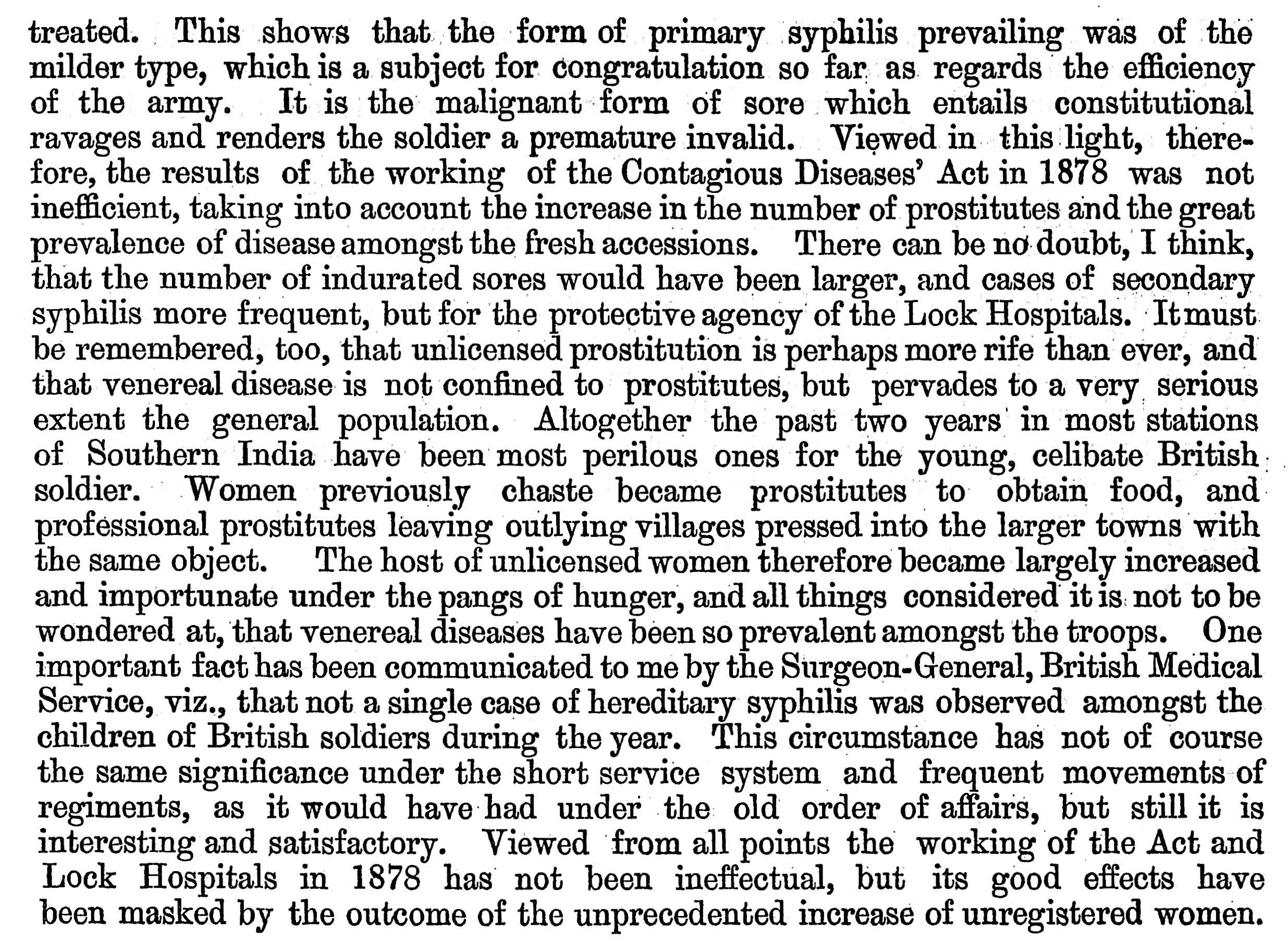

Figure 2 - Notes by the Surgeon-General of the Indian Medical Department in the 1878 Madras lock hospital reports. Source: https://digital.nls.uk/indiapapers/browse/archive/75112311

What this passage about lock hospitals in the Madras Presidency brushes over is the famine that affected large parts of India from 1876-1878. Starving women turning to sex work in order to survive is portrayed as a nuisance which needs further regulation rather than the result of calculated economic exploitation by grain exports that were ongoing even while millions of Indians were dying. This shifted focus onto the British soldiers at risk of contracting STIs highlights the overall priorities of the authorities compiling these documents and also uncovers the ways in which the colonial government created and solidified the ideas and concepts that were central to their rule (Risam 50).

* Lock hospitals existed in other regions of British India as well, but their records are not held by the National Library of Scotland. If you want to read about other regions’ lock hospitals, try searching the British Library

Works Cited:

Mishra, Sabya Sachi R. “Laws of Pleasure: The Making of Indian Contagious Diseases Act, 1868.” Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, vol. 60, 1999, pp. 550–61.

Risam, Roopika. “Colonial Violence and the Digital Colonial Archive.” New Digital Worlds: Postcolonial Digital Humanities in Theory, Praxis, and Pedagogy, Northwestern UP, 2018, pp. 47–63.

Stockstill, Ellen J. “Degenerate or Victim? Fallen Women, Disease, and the Moral Strength of the British Empire.” Nineteenth Century Prose, vol. 44, no. 1, 2017, pp. 21–38.

![Sassoon General Hospital, Poona, India: a queue of patients awaiting treatment. Wood engraving by [C.R.].. Credit: Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)](https://blogs.ed.ac.uk/digitalhumanities2020/wp-content/uploads/sites/2181/2020/12/Patient-at-hospital-in-India-960x707.jpg)