Ontology (‘what is’) is a topic students often have difficulty grappling with in their work. It tends to end up being a set of buzzwords that people lay fealty to (interpretivist! Social constructionist!) and generalist statements about society being ever changing and such. It should be a set of thinking tools that help you work through the research problem you are examining.

Plus it’s a great way to annoy and get the drop on existing researchers, which is what you should be doing. That is why when academics write we spend a lot of time saying what we mean by our topic, for example, I study illicit markets. What is a market, you rightly ask? It turns out to be contested and not at all ‘just what looks like one, numb numb’. Think of epistemology as the researcher’s shield against being wrong, which we really hate. This matters because there are real world consequences of claims about knowledge and how reliable and consistent it is, which you will see later. We need to know research theory works because we must grasp the underlying reality we report on and what matters about it. For example, we have plenty of statistical data about financial inequality, but when we ask people what matters to them they often refer to localized comparison with others in similar circumstances. What matters more when people vote?

In terms of epistemology, a recent case shows why it matters and how complex it is. The question being asked is how you show intention in order to prove fraud about scientific claims. Elizabeth Holmes’ company Theranos claimed to have a simple device that could test blood using a pinprick – radically better than existing systems that use centralized labs and larger blood samples. It was a complete impossibility for various immutable biological reasons (you cannot sample the ocean with a bucket). Nonetheless the company topped out at a multi-billion valuation before reality took an interest, resulting in an effect rather like that when Wile-E-Coyote notices he has walked off a cliff. Holmes argued that her claims were just the kind of salesmanship we see all the time. From a sociological standpoint we would ask some other questions beyond her legal culpability. For example, how the culture of Silicon Valley set the scene for Theranos’ failure, a culture that focuses on disruption, is scornful of existing, tacit understanding, and thinks that if you throw enough data at a problem you will solve it. Is this capitalism gone rogue or working much as intended? How is this kind of behaviour made normal? We look on crime as normal, as produced by the setting, not as exceptional and pathological.

So the questions we ask are not just ‘is such and such claim true or false’, but about what the conditions for truth and falsehood are. For example: Take the question ‘Why do women often suffer from hysteria’, occasionally asked back when hysteria was a thing largely male doctors attributed to women. The answer was, because they have wombs, duh. A more epistemologically nuanced question becomes ‘why are women being diagnosed with hysteria a lot?’ shifting the focus to the people doing the categorising, then ‘What is it about the definition of hysteria that means it is applied to typically female experiences’? And ‘Is the label being used to control women? What does that say about society’? Medicine is a great study because it tussles with these entities all the time: addiction, mental illness, physical typologies, all are malleable, moving targets with a large helping of cultural assumptions behind them. Other problems stem from flawed cultural epistemologies. One is the claimed CSI effect in juries. Because of shows like CSI it is alleged that juries in criminal trials expect an unrealistic degree of certainty from forensic science, which is never there, and treat doubt as equivalent to failure of the science. So there are problems of producing certainty where there is none, which is a big problem in public policy, and the reverse, turning reasonable uncertainty into unreasonable doubt.

This is all about avoiding fallacies in reasoning, so we can point at those others make and laugh. Fallacies come in leaps of logic. One I hear a lot is ‘People with racist views voted for Brexit ergo Brexit happened because of racism’. The second assertion is not proved by the first. Any sociological research sets up a chain of logic and we need to be sure each link in the chain is solid. We need to be clear about what we do not know, what is not certain, before starting to claim what is.

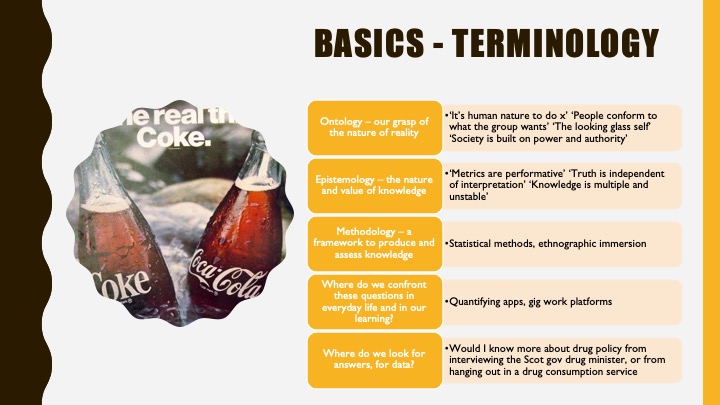

Your basic cheat sheet is:

Ontology asks what its nature is: the cosmology of the real. For Erving Goffman, the nature of the self is as a dramaturgical actor. We want a handle on what social reality consists of, what forms and types does it contain, how do they behave towards each other.

Epistemology asks what the nature of knowledge is, how can these forms be known about, how it is made meaningful. So it is both about how we assess it and communicate it. The hierarchy is a bit wrong, really epistemology comes first – how did we start with an idea of human/nature split in the first place without an epistemological stance on it that formed our ontology.

Methodology is the framework or strategy to do the work. Methodology shapes our everyday lives. A quantifying app tells us: humans can be compared, and are in competition even if just with ourselves/our bodies. Tells us our bodies are a resource over which we have power. University rankings. The creation of a hierarchy and certainty. So epistemology has real, direct effects on the world. We can then question our ontological understanding, like the background assumption that only humans make decisions/are selves. Algorithms say different.

Finally we get to what we want to look for in our methods, our techniques. Where does this reality appear? Is it where you think? Would I know more about drug policy from interviewing the Scot gov drug minister, or from hanging out in a drug consumption service?

Finally we get to what we want to look for in our methods, our techniques. Where does this reality appear? Is it where you think? Would I know more about drug policy from interviewing the Scot gov drug minister, or from hanging out in a drug consumption service?

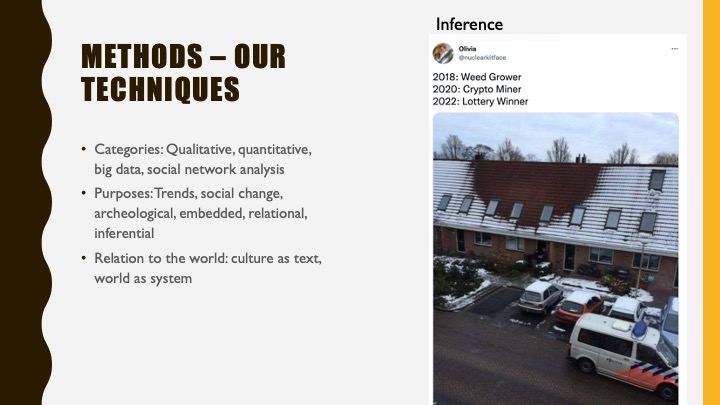

We can divide up methodological types based on the qualities of the data produced: Qualitative/quantitative/big data/social network analysis are common typologies. But we can also divide them up by purpose: There are trend approaches, where statistics are useful. Social change, where biographical or oral history is helpful. Archeological methods that sift and uncover the hidden history of an entity. Embedded methods like ethnography. We can also slice our techniques up by their relation to the world. For example, Geertz approaches culture as a symbolic text, while Levi-Strauss sees it as functional, relational system, abstract from the meanings given by people doing it.

In order to get closer to the language we should use, Llet us name different types of approach through the controversies around them. Ontology has two aspects. First, it is the set of ground truths – basic accepted reality claims – that you take as elemental to your study which limit how you can study it. Second it is a set of disputes about the nature of social reality and evidence about it which both affect your research and that can be studied as part of it.

In order to get closer to the language we should use, Llet us name different types of approach through the controversies around them. Ontology has two aspects. First, it is the set of ground truths – basic accepted reality claims – that you take as elemental to your study which limit how you can study it. Second it is a set of disputes about the nature of social reality and evidence about it which both affect your research and that can be studied as part of it.

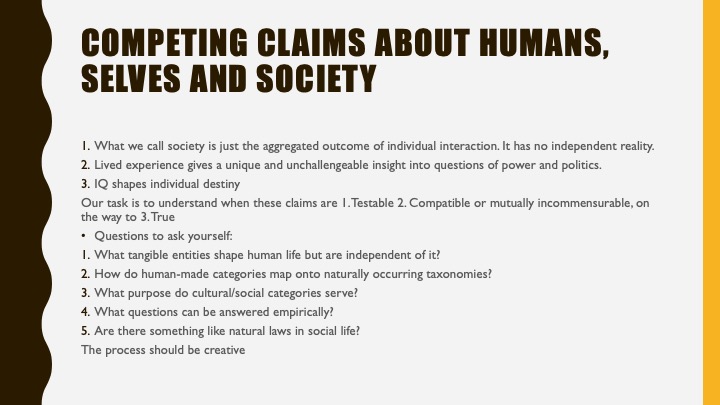

- To illustrate both, here are some competing ontological statements:

- What we call society is just the aggregated outcome of individual interaction. It has no independent reality.

- Lived experience gives a unique and unchallengeable insight into questions of power and politics.

- IQ shapes individual destiny

These are framed in a straw man style so we can have an argument. Each statement claims a ground truth about an element of social life which is fundamental to it. Each is structured something like ‘before we consider anything, we have to consider this’. Before talking about education outcomes, we have to consider that children enter the education system with a set of capacities measured by IQ, which shape outcomes far down the line. Before examining how people group themselves into functioning units we need to see how they create boundaries through interaction. Before considering experience we must understand subject position.

- How are research problems produced from these statements? Consider also what might falsify each of these statements. For example, if you studied intersectionality and found that class position was dominant. Or that sex mattered in a way that was fundamentally different from other identity categories. What obdurate facts are lurking in the wings waiting to derail things?

Our task is to understand when these claims are 1. Testable 2. Compatible or mutually incommensurable, on the way to asking 3. Are they true. People often leap ahead to point 3 based on whether they like them or not. We have to roll the chain of logic back a bit and start with what each claim says about human nature, and human agency. This shades into the politics of research, because these questions are innately politically charged ie liable to really piss someone off.

In terms of your own topic, there are questions to ask yourself:

- What tangible entities shape human life but are independent of it?

- How do human-made categories map onto naturally occurring taxonomies?

- What purpose do cultural/social categories serve?

- What questions can be answered empirically?

- Are there something like natural laws in social life?

The process should be creative. For example, let us examine gender symbolism in clothing. Take a near example: is a kilt a skirt? Why not? Does it depend on who is wearing it? We thus generate a flow of questions to produce insight. We find there is not an inherent ‘kiltiness’ to the object, its kilt-ness is a combination of symbolism and context. We apply that to other naturally occurring categories so that every question is theory dependent. There is no biological basis for the category of illicit drugs that includes heroin but excludes alcohol, but that category matters. Another trick case in point is how we train machines to recognise human categories like spam email. You need to agree what spam is first of all which is trickier than it first seems.

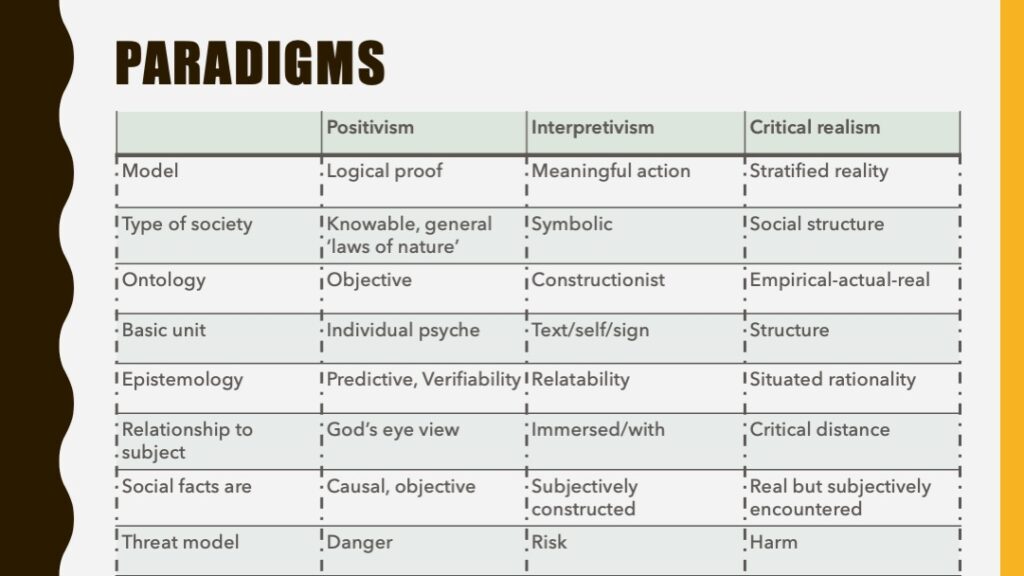

Think of this slide as a map for your research logic, which you can do to trace your path through some of these questions. Be aware of what we mean by specific terms. For example ‘laws’ means something like the natural laws classical science studies (very different from for example quantum physics). We come across this all the time in computer science. For example, ‘King’ or ‘Prince’ occur a lot with words signifying power and status, but ‘Queen’ and ‘Princess’ not so. Is it just a question of producing more accurate knowledge? For example, a lot of medical diagnosis derives from limited datasets that often exclude women – see the symptom galaxy for hear disease, drug dependence, and autism. So we miss things. Or over include people in developing countries where lots of pharmaceuticals are tested. So is solving that problem just a matter of adding more data (positivism) or is there something more fundamental amiss (critical realism)? You can link that to your threat model. In each paradigm we model threat differently. In the case of the drug fentanyl, there are objective dangers due to its material qualities, users approach it in terms of risk positioning, and we can point to supply chain harms produced as a result of dealer incentives in the illicit market. Here is a good example of how harms are produced and then localsed through a system of global incentive structures.

Think of this slide as a map for your research logic, which you can do to trace your path through some of these questions. Be aware of what we mean by specific terms. For example ‘laws’ means something like the natural laws classical science studies (very different from for example quantum physics). We come across this all the time in computer science. For example, ‘King’ or ‘Prince’ occur a lot with words signifying power and status, but ‘Queen’ and ‘Princess’ not so. Is it just a question of producing more accurate knowledge? For example, a lot of medical diagnosis derives from limited datasets that often exclude women – see the symptom galaxy for hear disease, drug dependence, and autism. So we miss things. Or over include people in developing countries where lots of pharmaceuticals are tested. So is solving that problem just a matter of adding more data (positivism) or is there something more fundamental amiss (critical realism)? You can link that to your threat model. In each paradigm we model threat differently. In the case of the drug fentanyl, there are objective dangers due to its material qualities, users approach it in terms of risk positioning, and we can point to supply chain harms produced as a result of dealer incentives in the illicit market. Here is a good example of how harms are produced and then localsed through a system of global incentive structures.

Critical realism sets out a distinction between empirical (observable) actual (events generating observed phenomena) and real (causal mechanisms, structures) Epistemology matters because of the kind of questions we CAN ask within its terms e.g ‘Is this claim true?’ ‘Does x affect Y’ ‘What matters about Z’ In my work I use all of these paradigms. My research projects ask did COVID restrictions shift people from social supply to commercial drug dealing? (yes, a bit). Does the digital drug market change what drugs are? Yes, it makes them into commodities and users into rational consumers.

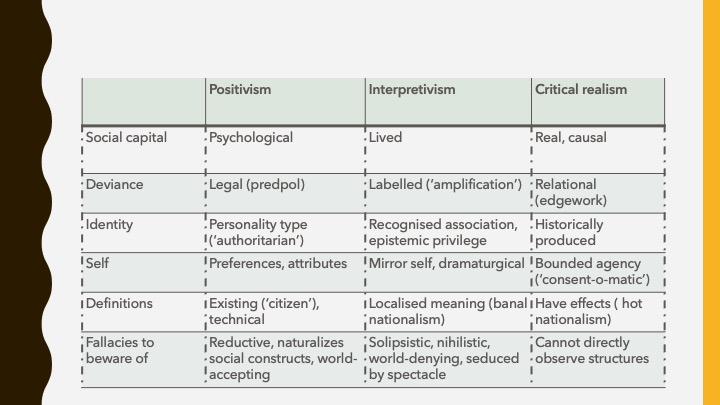

This next slide is a map through some different concepts as they appear in each paradigm. It matters because people use the same term to mean different things and different terms for the same thing. Some categories are powerful over us and some less so. Some are salient in specific contexts only. Eg being a ‘British citizen’ is not the same as ‘Being/feeling British’.

- This and previous slides should be a cheat sheet to help you critique existing research and theory in these terms

Really we are talking about levels of analysis. For example: I know that there is such a thing as organized cybercrime, which causes harm – I can measure that a bit. I also know that some people are criminalized for white hat hacking activities, and that groups might appear organized without being organized, and that harm is very variable and unevenly distributed. What I’d want to know is the type of society that permits some harms and suppresses others.

Really we are talking about levels of analysis. For example: I know that there is such a thing as organized cybercrime, which causes harm – I can measure that a bit. I also know that some people are criminalized for white hat hacking activities, and that groups might appear organized without being organized, and that harm is very variable and unevenly distributed. What I’d want to know is the type of society that permits some harms and suppresses others.

The best way to understand ontology as a concept is through tracking disagreements in your field. Here is one: at the moment medical startups are seeking to develop psychedelic treatments that do not have psychedelic effects. This is part of legitimating the treatment as a medicine. But many people in the psychedelic community do not see the positive effects as separable from the psychedelic experience and see this is a questionable, somewhat hostile move. It involves giving the psychedelic qualities that we resist: consistency of effect, predictability. In the view of psychedelic culture this makes it ‘not a psychedelic’. Which is about the unifying of consciousness and the creation of insight about self and the world.

The same disagreement played out over cannabis’ analgesic properties. Can you produce a drug that separates out its intoxicant effect? Is it the same drug, and the same experience? These are ontological questions. Questions about what the object is, fundamentally.

- This takes us from ontology to epistemology, which asks where knowledge about the world derives its authority from. In the one case, the source of authority is political expediency. In other places it is traditional authority, or ‘it’s aye been that way’. The quality these have is there is something in it that refuses to be questioned. Guess what our job is? To be the annoying person who won’t stop asking ‘but why though’.

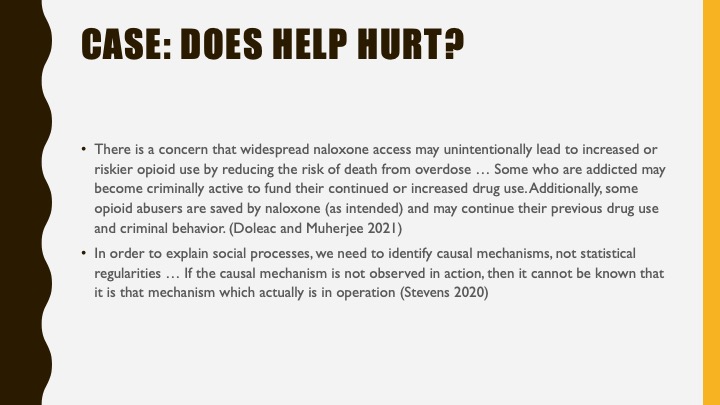

- The case is based on the debate around this article: Doleac JL and Mukherjee A (2021) The Effects of Naloxone Access Laws on Opioid Abuse, Mortality, and Crime. The Journal of Law and Economics 65(2): 211–238. DOI: 1086/719588. and insight from Stevens A (2020) Critical realism and the ‘ontological politics of drug policy.’ International Journal of Drug Policy: 102723. DOI: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2020.102723.

Controversies come into view when we discuss cause – often reduced to ‘spooky action at a distance’ which we want to avoid. Examples of that are: video game violence causes real world violence (how exactly Civilization VI does that I don’t know). You do not hear much about that complaint now video games are ubiquitous. Instead the ‘threat’ has shifted to online communities of incels and the alt-right.

Naloxone is an opioid antagonist used to counter overdose. A potential life saving medication. In the US a ‘naloxone in every medicine cabinet’ approach has been followed to ensure heroin and other opiate users have immediate access. Doleac and Mukherjee say, hold on. They examine the effects of universal access policies in terms of moral hazard, risk adaption. The theory is that for example cars that feel safe make people drive in a more dangerous way. They use a natural experiment of US state level policies. They make relevant points: naloxone is not a magic bullet, such things do not exist in this field. Any change induces a change in behaviour. Drug users are risk aware and have agency, are rational choice users. The study was criticised for, as Stevens sets out, problems of shallow ‘cause’, absence of theory, assumption about objective entities interacting without meaning. For example, rationality is bounded by circumstance so we cannot reduce choices to rational order preferences. The correlation Doleac and Mukherjee demonstrate does not prove moral hazard at work. One would need to look closely at users’ accounts of their motives in context in order to get closer to the ‘real’, the underlying structures and mechanisms. Moral hazard remains unproven. Get ontology wrong and people might die. No pressure.

If you would like to learn more yourself, here is an exercise to do: read Palmieri, M., Cataldi, S., Martire, F., & Iorio, G., (2021). Challenges for creating a transnational index from secondary sources: The world love index in the making. In SAGE Research Methods Cases Part 1. SAGE Publications, Ltd., https://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781529762037

- Ask yourself the following questions:

- What does GDP measure, and why are people critical of it?

- Can we really ‘measure’ love as proposed?

- What other measurements have you come across that might matter to us? For example, you might see life expectancy, or average incomes, or measures of pollution, or other claims about some aspect of reality which are based on social research.

- What are the social and political consequences of selecting different measurements of aspects of social and economic life?