Research is a process of constantly theorizing from evidence. In order to give our findings life and meaning we can apply frames that allow us to do that and also help us work together and react to practical problems as they come up. One frame is normalization. As sociologists we deal with the problem of how the normal comes to be, and a good angle to work is where people have to reconcile contradictory realities. often when people want to maintain their sense of being moral but also do what they want. For example, the town of Wick in Caithness was dry for many years so after Sunday Church residents just took the local train to the nearby village Lybster to get drunk. God couldn’t see that far. The trainline largely existed for that purpose. Another frame is looking at competing working concepts of the same object. At times, we want to work together on the same subject without agreeing what it is. For example, to many people I know psychedelics are semi-spiritual objects that can be used to work your way through addiction. To pharmaceutical startups, they are potential medicines that can be used to treat addiction. We want them to be legalized for this use but do not have the same sense of what they are, their ontology. They work towards ‘definition of the situation’, our shared consensus on what is real and what matters. The Protestant Ethic is one: wealth reflects thrifty hard work and moral piety. Working in a group you need your own local DOS to work together and lean into. You come towards one by working together, and problems arise when we do not have one. This is all about building resilience, knowing when you are hitting a wall and turning threats into opportunities. Each positive and negative adds to our research image, the way we frame our research object. Above all, there are few genuine blocks in the road. Each disagreement, moment of uncertainty, is a turning point.

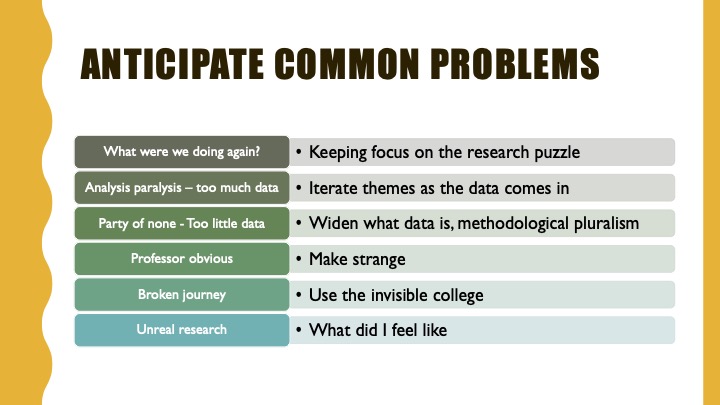

The first step is characterizing typical problems researchers often face.

- What were we doing again

When you work with different frames or just get lost in the weeds you can experience loss of coherence on the project goal, sometimes because we lose sight of what puzzle we were trying to resolve or our end goal. Now you want to go back to the underlying puzzle, the ‘so what?’ factor in the study. For example, in our Reddit study we spend a lot of time on the technical challenge and need to keep focus on the underlying social purpose.

- Analysis paralysis

There can be a sense of drowning in data that comes not from too much data but too much choice – we could say so many things. Your research questions should help you begin to structure and select.

- Party of none

You can end up with too little data to describe the case. Firstly, question what ‘too little’ means. You might have few interviews but lots of rich insight from them – in fact, one interview is enough if it is the right one. To generate more angles on the topic, adopt methodological pluralism.

- Professor obvious

Nobody likes it, everyone feels it. I have spent a lot of time stating what it feels like everyone knows. This can be a good sign as it shows your familiarity with the topic. What is obvious to you might not be to anyone else. You can dowse this feeling by making the familiar strange. Explain what matters about it to someone else, and in different contexts.

- Broken journey

There are various possible stage failures, of ethics, gatekeepers, other bumps on the road. As what the research bargain is, what your gatekeepers or respondents are getting or how they see themselves in the research. You can also treat noise as a signal, turning weaknesses into strengths. Why something did not work is also useful data.

- Unreal research – the sense of not reporting on anything

You can get a kind of brain fog about your work, the sense that is has no texture or structure. The answer to this is to personalise –ask how do I encounter this topic? What does it feel like? And also link back to your researcher’s theory about the subject matter and why you are studying it.

A way of addressing at least some of these problems is to work them into your plan

- Co design

As part of the process, ask research participants’ and audiences what matters to them. What should be being researched? What are the priorities and why?

- Your research team and you have an invisible college to work with

The community which exists around your research – your classmates, the people you speak with about it, who give you informal feedback all the time.

- Co produce findings.

These two – the co-design community and the invisible college community are great for road testing your findings as they emerge

- Storyboard your research

As technique you can pair up with a team member to ask questions of each others’ data.

- Start working with data as soon as you have some

Start by characterising the data you have in terms of your immediate response to it. Interviews can be good and bad – some effusive, some monosyllabic. Techniques like use of silence, repeating the last 3 words they said, can help encourage people out.

- Good interviews have a shared understanding of the world, ask what matters, how it happens.

Less strong interviews are thinner, more like a Q and A, or cautious. For example, too many interviews I have done with powerful people just get the public story. It takes ethnography to get backstage.

This excerpt is from our co-designed project on women students’ pre-drinking rituals.

- You can also comment on the qualities of the data we did not notice at the time – ethnicity, class, what was not said.

It turned out they had very different understandings of what ‘data’ was.

- Ask, what qualities am I brining to the research? What are the everyday politics, the sociological meaning, of this study? As a man there is a limited way I can engage with women’s pre-drinking rituals.

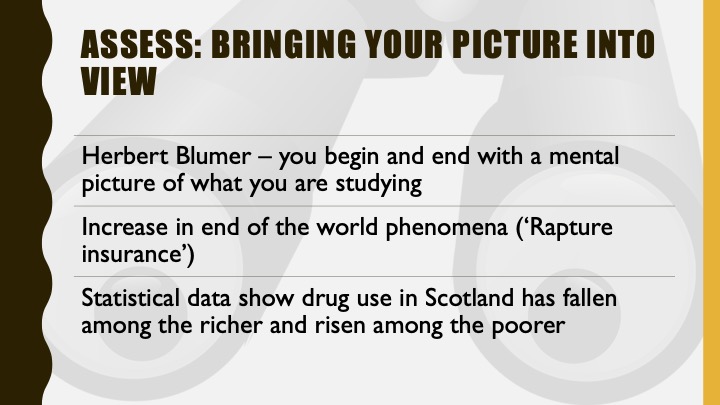

So we build up a picture. Herbert Blumer said that you begin and end with a mental picture of what you are studying

Blumer is quoted as saying this in Becker HS (1998) Tricks of the Trade: How to Think about Your Research While You’re Doing It.

As Becker puts it ‘the basic operation in studying society—we start with images and end with them—is the production and refinement of an image of the thing we are studying’. In your mind you have a mental picture of your topic, and you use various data to refine that and get closer to an understanding of its nature.

- Everyone has images of society, sometimes cliches about the lives of others.

Images can be myths – for example, the ‘white opioid epidemic’ in the USA/Canada – which while not really true does serve a purpose in framing public discourse on the issue. We can use data to show the myth is untrue, but that is inadequate in terms of having an effect in the world. We need to create a robust narrative that is supported by data which shows the reality. Images – not being literal here – are persuasive. The difference between being a scholar and a polemicist is how our images are tempered and enriched by empirical data.

- Critically we ask what does data see and not see.

The UK Census counts only certain categories

Two phenomena little understood:

- Increase in people who expect Rapture and provide services for them. Guaranteed atheists who will look after your pets.

- Scottish drug use data. This is one fact that is never mentioned in relation to drug deaths.

There is a seriously incomplete picture which does not grasp for example inter generational harm.

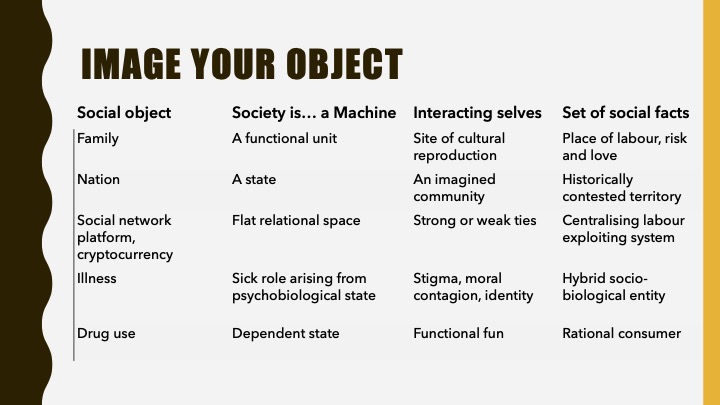

Some specific research images which link to your research theory

- We tell about research as a sequence of metaphors or images about what it is, drawing on our ontology – the big picture of which our research is a small slice.

- This storyboards some concepts by contrasting different metaphors/images according to different social ontologies.

Consider how the object appears in these different framings, or definitions of the situation. A family serves social functions of demographic reproduction and socialisation. Or it reproduces culture across generations. Or it is a place of competing and sometimes exploitative relations around divisions of labour, risk of violence, and love/obligation. We come sometimes be persuaded that love exists in human affairs. A nation is in much international affairs assumed to be the same as the state, which it is not. In everyday lives it is an imagined community. In Weberian terms it is contested territory. Social networks advertise themselves as ‘flat’, user generated spaces. In interactional terms we would think about the meaning and strength of the ties that exists in them, and in critical terms look at how they undermine themselves by centralising and changing the terms of the labour process. Illness we can see as a well defined ‘sick role’, a relational stigma or identity, or a hybrid of societal constructs and neuro-biological substrates. Crime and drug use divide along the same lines, from pathology to performance to situated rationality.

- Practical questions you can use to create your image:

As what are the conditions in which these attributes become real for our research subjects. In what ways does this image change as you conduct the research?

What is the relationship between image and your emerging research story?

Do definitions produce the situation? Eg there is a tendency of US/UK law enforcement to divide ethnic minority youth into gangs produces ‘gangs’ as the frame for youth crime and for ‘ethnic minority male youth’.

- Drawing a lot on Becker’s Tricks of the Trade here

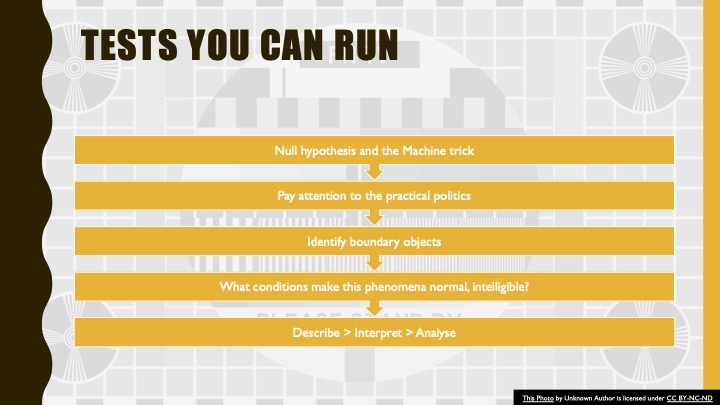

Apply the null hypothesis which assumes these variables are only connected by random chance. What is the evidence that they are not? We can apply statistical tests, or other evidence about causal processes. A null hypothesis would be: any actor is equally likely to be cast as Galadriel in the Rings of Power. Any person leaving prison is equally likely to reoffend.

- Another version of this is that these acts are random, such as violence. Is street and domestic violence random, or do we see a pattern. For example, public violence between police and protestors is often slightly theatrical and targeted, excluding ‘non-player characters’.

These tests involve introducing a kind of artificial naiveté. We know true randomness is rare in social life

- Are people doing this activity because they must, or because they enjoy doing it?

Draw the decision line or the opinion line e.g the choice to take heroin is the culmination of a series of prior choices, or a series of contingencies

- Machine image focuses on the outcome as a product – how does the institution produce this outcome.

How does an elite school produce elites (as opposed to its formal educational mission)? How does a prison produce crime/reoffending? Like the imaging process this asks us to imagine the purpose of the institution is not its explicitly stated aim. From Weber’s perspective, bureaucracies exist to perpetuate themselves. From a critical perspective, the medical and legal professions exist in the way they do to maintain professional closure. So the GMC or Bar Associations’ roles in this framing are not about ensuring quality but maintaining professional status and autonomy and protecting members from the lay public. Keep in mind what is not explained by the explicit public accounts of what is – the obdurate path dependencies that exist because they always have. Return to those earlier ontological ideas – do people have characteristics? Do they strategically deploy them?

- This is about finding the practical politics

The tacit, tangible way of doing things that ‘everyone knows’.

- Identify boundary objects

We work together best when we are explicit about shared ground truths, and also explicit about where we differ. Groups that include members from different disciplines often develop boundary objects which allow information to be translated and collaboration to happen across different disciplines or cultures. In Intensive Care Units (ICUs), the patient whiteboard or chart functions as one. This lets nurses, dieticians, pharmacists etc keep track of relevant, meaningful information. Field notes, checklists, maps, allow us to work together even if we do not have a consensus about what is going on (see the argument in Bowker GC and Star SL (1999) Sorting Things out: Classification and Its Consequences. Inside technology. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press). For example, we can agree that there has been an upward trend in drug related deaths even when we don’t agree on how those are classified. We come to a compromise agreement. We need to ensure e.g we are using the same terms for the same thing. Like securitisation. In security studies that is a good thing and in political theory a bad thing.

It is all about how it appears in the specific context e.g emotional regulation in cybercrime communities, from people who are script kiddies but want to be professional cybercriminals.

- Your story starts with intense description (what it is like), moves to interpretation (what it involves) and finally to analysis (what it signifies, what the consequences are)

Finally let us personalise this

You are the instrument of your research. Your position changes, perhaps from outsider to part insider, or in the other direction for ‘native’ researchers. We can tell this happening because of our grasp of the language, and our need to code switch. Your position in relation to closeness the topic. As an example, studying Roma-Gypsy-Traveller communities I became very sensitised to what was not said, particularly about conflict within and between groups. In social life often what matters most is what is said least.

Molotch asked us to be be vulnerable to real life, to being affected, and to feel what it is like to live. For example, can you study drug trades without knowing the experience of being arrested, the sudden existential shift that brings? How many sociologists have been arrested? More than a few, if you ask.

Now, try this at home:

- The lecture highlights common challenges in doing research and invites you to talk about any you may have faced.

- To prepare we would like you to review: Wolkomir, M., (2018). Researching romantic love and multiple partner intimacies: Developing a qualitative research design and tools. In SAGE Research Methods Cases Part 2. SAGE Publications, Ltd., https://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781526429520

- Be aware this mentions domestic violence. Review the interview excerpt in it. We want you to think about how researchers respond emotionally to difficulties that arise in the research process.

- Consider:

1.Did the interview questions elicit a specific response in the interviewees?

2.Are there other research techniques that could be used which might involve more distancing or which would allow interviewees to talk freely about their responses?

3.Are there issues that the researchers did not pick up, such as domestic violence? Why was that?

Comments by Angus Bancroft