KB History – Chapter 3: Consolidation, a new war and a fight for survival

The end of the first phase: King’s Buildings Union

After the opening of Geology’s Grant Building, it would be some time before there were any other major academic building developments on the campus. The University Union had, however, been lobbying for a permanent building there since 1929, having spent seven years in the shared wooden huts behind the Chemistry Building. The Principal, eminent geologist Sir Thomas Holland, took a keen interest in student sporting and social activities, and it was a concern to him that the campus common room was described as “leaking and rat-infested”. With poor amenities, the campus was deserted after 5pm, as well as at weekends and during vacations. In the early 1930s the Union produced plans for combined social and academic facilities, and Holland managed to persuade the University Grants Committee that, with five departments already relocated, there was a considerable number of staff, students and visitors to the campus, and that investment in such facilities was justified.

Begun in 1937, the building later known as the KB Union was opened in 1939 and the final sections of the YMCA huts were demolished. The Union was arranged on an L-plan, with a lounge and balcony overlooking the tennis courts to the south of the geology building, and – unlike the more classical academic structures – had something of an art-deco feel, relatively luxurious at the time.

The KB Union building (to the left of the chimney) with its distinctive L-shaped design, looking out over the tennis courts.

The last building project at the science campus before the Second World War, the KB Union marked an important stage in the development of King’s Buildings, conferring status on an undertaking that had often been described as “a colony of the University”.

And yet the future of the campus would hang in the balance throughout the 1940s, as battles were fought for the location and layout of the entire University, centred around George Square.

With five academic buildings, the union and its sports pitches, the new King’s Buildings campus reached the end of its pre-war development. As had been planned, there was still plenty of land for further buildings, but these would have to wait for more than a decade: while Professor Crew was hosting the prestigious 7th International Congress of Genetics, scheduled for the last week in August 1939, war was declared. Soon Crew and other staff and students would find themselves called up for military service (although this time there were exemptions for applied science and medical students), while the KB Union became a headquarters for the Air Raid Protection units and the Home Guard.

As the Second World War intensified, 1940 saw the closure and demolition of the West Mains Steading, which had remained on the KB campus next to the Chemistry Building since its opening in 1919; the campus was now solely used by the University.

The only picture of KB in the 1940s, taken by a Spitfire from 12,000ft as part of the OS survey of Scotland, shortly after the war. The West Mains steadings have vanished, and one can clearly see the first wave of campus buildings in a site surrounded by the golf course, its land still being owned by the University. This image makes an interesting comparison with the diagram later in this chapter, showing the proposed relocation of the entire University to King’s Buildings.

Grand plans

As early as 1928, with only Chemistry fully operating on campus, there had been calls for the ‘re-integration’ of the outlying areas of the University, in particular to bring the facilities at King’s Buildings back to the centre of town. But the scale of the problem brought it within the field of urban design, entailing substantial development within the congested Old Town, as was seen when the City commissioned an architect to look into the various issues affecting the city centre.

In March 1931, the City published ‘The City of Edinburgh: Preliminary Suggestions for Consideration of the Representative Committee in Regard to the Development and Re-planning of the Central Area’, thankfully shortened to The Mears Report. As described in the previous chapter, Mears – an influential figure in the Cities Movement of the 1920s and 30s, adopting a ‘scientific approach’ to urban development – supported the return of all University facilities to the centre of town. Although his plans were not acted upon in the 1930s, due to the general social and financial dislocations of the depression and the beginning of the Second World War, the ideas put forward by Mears and others would gain traction as the 1940s progressed.

With the country at war, all major University building work was suspended, but plans were still made for expansion with the realisation that the post-war social era would be very different from the preceding one. A change in school-leaving age in Scotland at the end of the war, and an increasing birth rate in the 1940s, coupled with a political commitment to offer university places to all who qualified, meant that there would be a huge increase in building for all educational establishments. Additionally, in 1946 it was proposed to increase science student numbers from 55,000 to 90,000 in ten years, if Britain was to remain competitive in a post-war world. More money would come from governments, replacing the pre-war approach of donations from wealthy benefactors and charitable trusts.

The University’s plans were intertwined with those of the Edinburgh City developers, and throughout the period of the war discussions took place to decide on both the shape of the new post-war city, and one of its foremost institutions.

In 1943 the Clyde Report was issued, recommending that the University return to one location, redeveloping the areas around Old College and High School Yards, and returning all of the King’s Buildings departments to the city centre, a proposal endorsed by the University’s Post-War Development Committee (PWDC). There were problems, however, in the proposed redevelopment, most notably the number of residential tenements that would have to be removed (and tenants rehoused, a long-term proposition). The site was also heavily polluted.

Attention turned to the area surrounding George Square. Plans were put forward for the significant redevelopment of the area, from the removal of a few buildings on two sides, to the wholesale clearing of the entire site and the installation of major new structures; the latter approach would be necessary if science facilities were to return here. In 1947, the University published its plans for the surrounding area (figure below).

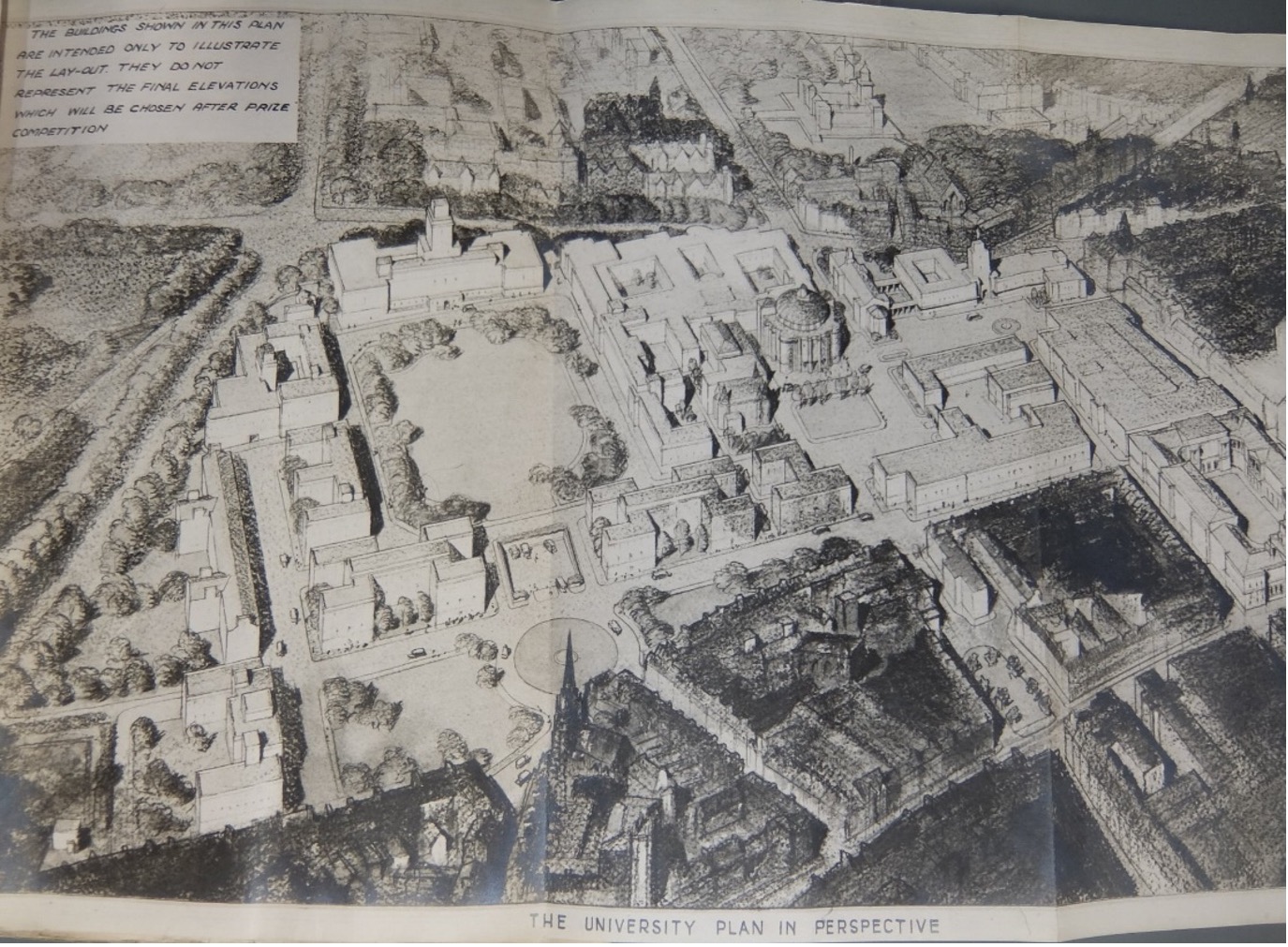

A 1947 sketch illustrating the outline proposals for a university zone on the south side of the city, with a redesigned George Square.

The report was a public relations disaster: there were strong objections from many prestigious institutions to this wholesale destruction of the terraced square, including the Cockburn Association, the Saltire Society, the Society of Scottish Artists, and the newly created Edinburgh Georgian Society (although to be fair, this society was created with the express purpose of objecting to the plan). Public and media opinion was also hostile.

In 1949 Sir Edward Appleton took up the post of Principal, one of his aims being the final resolution of the problem. He called upon the PWDC to consider four options for future development:

- Plan A – development to the east of Old College and South Bridge (the original Mears report);

- Plan B – development to the south of Old College, on the land between Nicolson Street and Potterow;

- Plan C – Abandonment of all city centre schemes, relocating all University premises at the King’s Buildings site; and

- Plan D – the redevelopment of George Square. While this initially included the idea of complete reconstruction, it was finally agreed that a partial rebuilding would be acceptable to the city, but that the plan for full reintegration of the science departments would have to be abandoned.

Plans A and B were rejected for the reasons described above: most notably, significant and expensive demolition and rehousing would be needed, taking considerable time.

Plan C: how the world might have been…

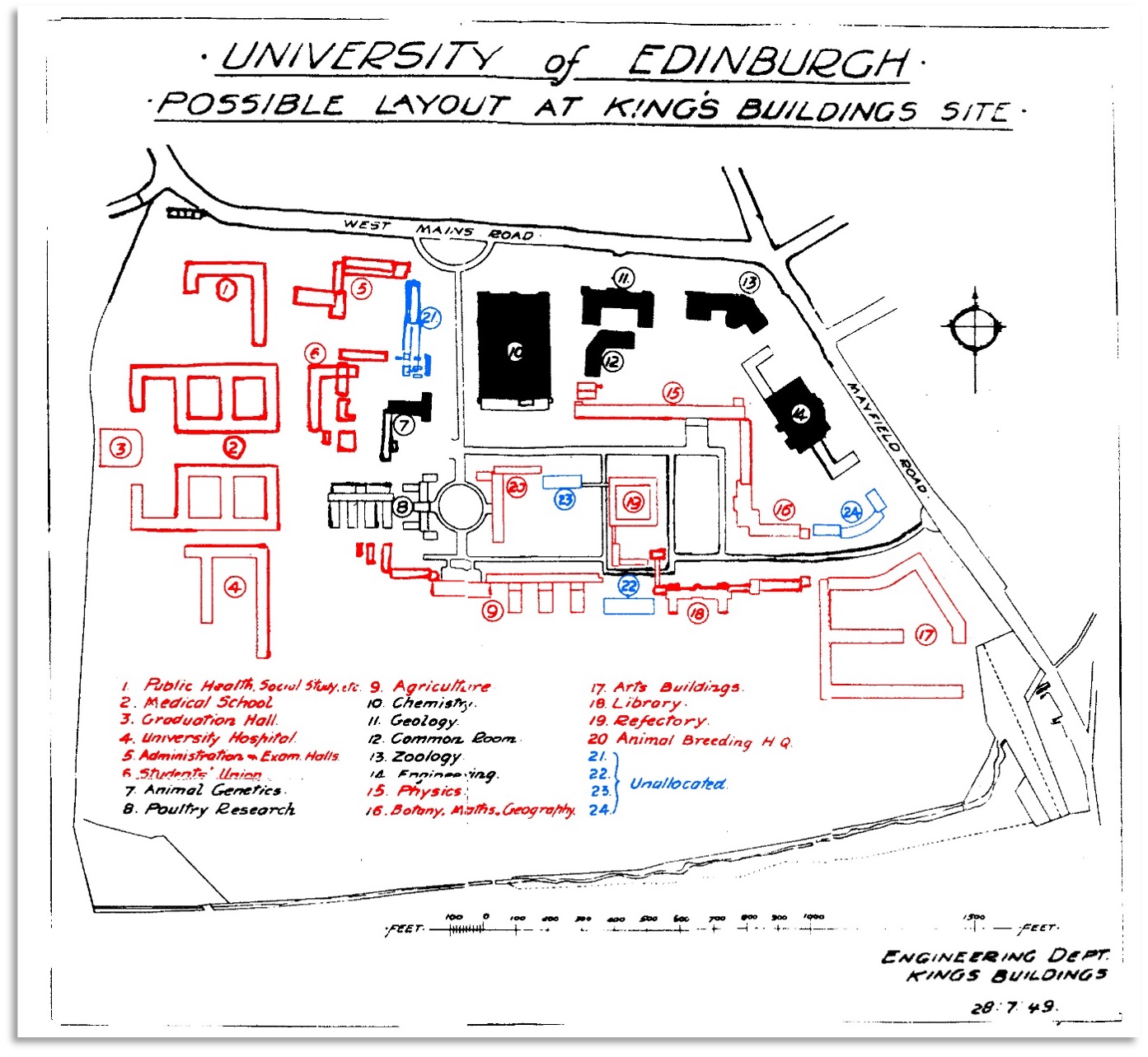

Plan C had been included as a contingency, should Plan D – which was now seen as the most realistic option – be rejected. In truth, there were several strengths to the idea of wholesale relocation of the University to the West Main’s site. Funds from the sale of old, cramped city sites could be used to create modern, purpose-built facilities, including the medical school and library. (There were even suggestions that the central hospital be relocated to a nearby site, which now seems somewhat prescient.) The University owned the surrounding land, including the golf course, so there was room for substantial new developments, overcoming the overcrowding problems in the city centre. And the site was clean and unspoiled. The following 1949 sketch by members of the Engineering Department of a possible campus layout shows the plan’s ambition.

Bringing all of the central University facilities out to West Mains Road would have meant extending the campus to the south and west, reclaiming land from the golf course. [Colour added by the author.]

The PWDC finally recommended the dual development of George Square and the retention of the research facilities at West Mains Farm; this was approved by the University Court in December 1949.

The future of The King’s Buildings was assured, and its next major phase of building was about to begin.

Peter Reid, College of Science and Engineering

We are indebted to the following sources of information for this brief history:

- “Science at the University of Edinburgh 1583–1993”, Birse;

- “Building Knowledge: an Architectural History of the University of Edinburgh”, Haynes & Fenton;

- “The University of Edinburgh: an Illustrated History”, Anderson, Lynch & Phillipson;

- the collected notes of Des Truman, and many other College and University sources.

Recent comments