KB History – Chapter 2: The first wave of construction, 1920–1932

The expansion of The King’s Buildings campus in the 1920s and early 1930s took place against a general unease, both in educational institutions and the country as a whole. The Great War and its dislocations were still resonating throughout the population, and new political alliances and challenges were shaping Europe in unpredictable ways. The rise of fascism throughout the 1920s, and the slow recognition of the extremes of wealth and poverty in Britain, characterised by the General Strike in 1926, led many to question the foundations of a civil society. And by the end of the decade the Wall Street Crash and subsequent global depression would among other things alter the way in which the University was funded, and its plans for future expansion.

Against this background, however, extensive new developments took place at King’s Buildings, as the University began to extend – if not yet to consolidate – its science campus.

New developments: Zoology

Construction of the Chemistry Building (see previous chapter) had been completed (and the building formally opened) in 1924, although the laboratories and four lecture theatres had been opened for teaching and research since 1922.

In early 1924 the University’s Principal, Sir Alfred Ewing, proposed that Zoology (still housed in Old College) should be the next department to move. Despite substantial opposition to leaving the city centre, the same pragmatic considerations that had determined the siting of the Chemistry Building remained compelling now, and in 1926 a site at King’s Buildings was chosen, facing the crossroads at the corner of the campus.

In 1926 a donation of £74,000 from the International Board for Education enabled progress on the new premises. Despite his vociferous objection to moving any departments out to the KB site, James Ashworth (the future Professor of Natural History) was closely involved with the architects, considering such matters as the daylight then necessary for microscopy – the building depth was restricted to ensure good lighting – and demanding laboratory windows from bench height to ceiling. The museum was deemed of considerable importance, to house a large collection of specimens in mahogany cabinets, and its size led to the asymmetry in the plan.

The building was lavishly decorated externally with a series of sculptured panels executed by Phyllis Bone, depicting a range of animals in bold relief. Internally the banisters of the main stair were decorated with bronze sculptures (owl, cat and monkey, also by Bone), and a cast of Hugo Rheinhold’s famous “Ape with Skull” occupied an alcove on the landing.

Hugo Rheinhold’s “Affe mit Schädel” (1893). The spine for one of the books reads “Darwin”, while the Latin quote at the front – “eritis sicut deus” – is a Biblical phrase from the parable of the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil in Genesis 3.5.

In May 1929, the Zoology Building was officially opened by Prince George; Chemistry was no longer alone at West Mains Road.

The Institute for Animal Genetics

Edinburgh was an early pioneer in the subject of genetics, with a lecturer being appointed as early as 1905. Francis Crew was appointed in 1920 as Director of the Department of Research in Animal Breeding, the first of its kind in the UK. Initially housed in cramped accommodation in High School Yards, and then temporarily sharing space in KB’s Chemistry building, the department had to wait until 1930 for its own facility.

With funding from the International Board for Education (and Lord’s Forteviot and Woolavington), work began in 1928 on the Institute of Animal Genetics (later to be the Crew Building). Associated with the study of genetics in those days were considerable numbers of farm animals, and outbuildings were provided for sheep, pigs, goats, poultry and small animals, as well as a 30-acre farm on the campus site; this may explain why the building was located some way from the road, and from the other outward-facing structures. The rear-facing part of the Crew was designed to allow the building of an extension wing, making it an ‘H’ instead of a ‘T’, which never happened.

In a quote from Des Truman’s campus history notes: “Whereas other buildings had their opening ceremonies graced by royalty or by a Prime Minister, the Institute of Animal Genetics was opened [in March 1930] by a scientist, Sir Edward Sharpey-Schafer, the physiologist. In later years, the staff of the Institute acquired something of a reputation for radicalism and it may be that this was revealed in the choice of distinguished personage invited to perform the opening of the building.”

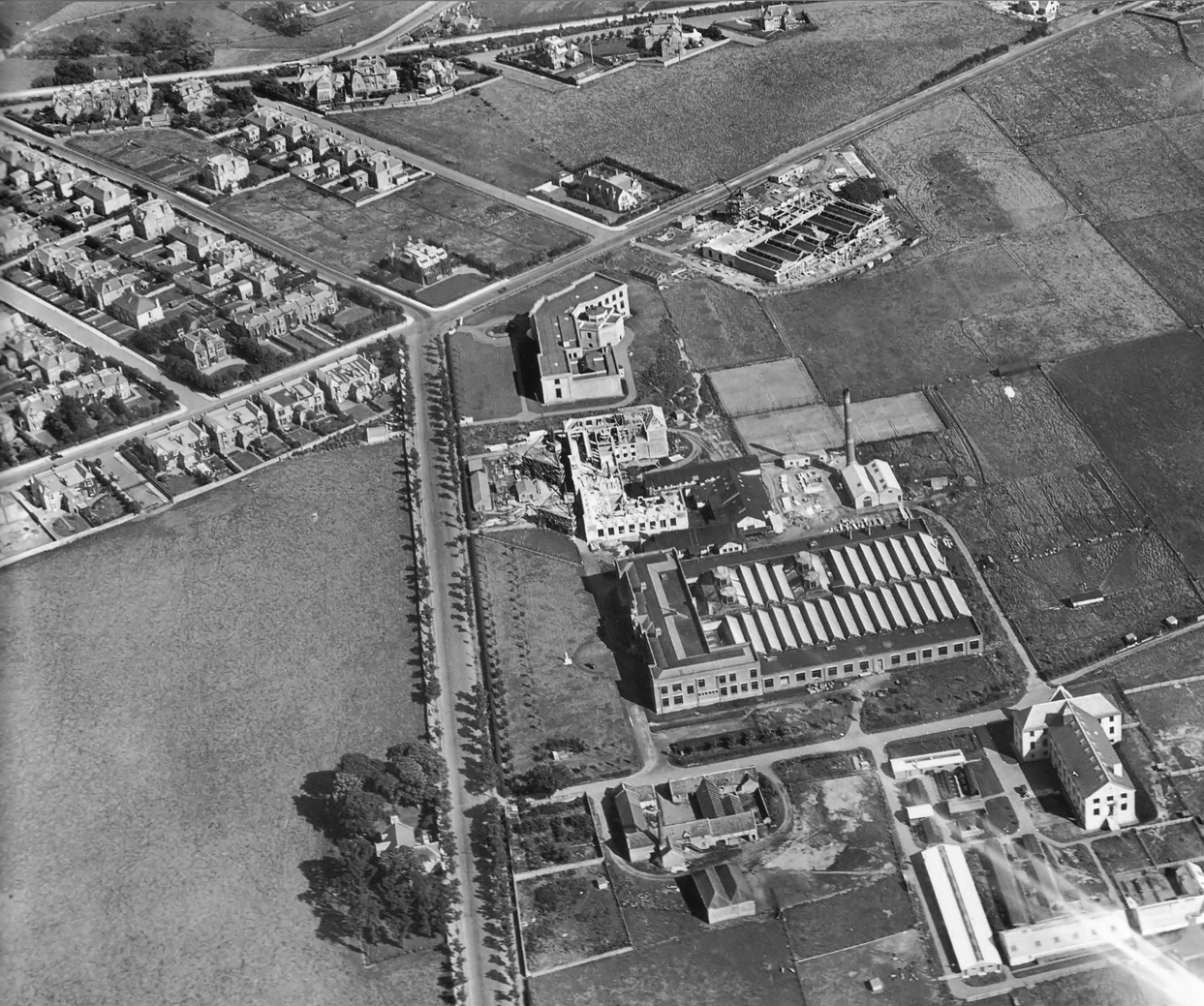

The campus in 1929. The Chemistry and Zoology Buildings are open; Geology are occupying their temporary square wooden hut; and the Institute for Animal Genetics is under construction. West Mains Farm Steading is still on-site.

Engineering expands into its new facility

The Department of Engineering had undergone rapid expansion in student numbers in the decade before the war, and development of the discipline had made it clear that premises much larger than the current accommodation – wooden huts attached to the High School Yards building – would be needed to house new experimental research facilities. Then in 1927 the University Court received news of a bequest from James Sanderson of Galashiels, a sum of £50,000 for the Departments of Chemistry and Engineering. As Chemistry was now well served by its new campus building, the sum was made available for the construction of new premises solely for the use of Engineering. The site selected faced onto Mayfield Road, with work commencing in 1929. Dedicated structures were created in the building to house equipment for specific research needs: the tall tower – housing water tanks used for gravity-fed hydraulics experiments – was the highest campus structure; in years to come it would be lost amid a crowd of taller buildings.

The Sanderson Building was formally opened on 28 January 1932 by Prime Minister Ramsay Macdonald.

Geology’s temporary “hut”, and its new home

As the 1920s began, the Department of Geology faced severe pressure upon its teaching space, and the available accommodation at Old College was entirely inadequate. Urgent action was needed, and as a temporary option the University purchased the large wooden YMCA hut that had ringed St Andrews Square, used by American troops during the war, and in 1923 relocated the structure to the campus, next to the Chemistry Building. For the next six years the hut would house Geology and the University Union, but this was a stop-gap solution. Fortunately, in 1929 the Scottish businessman, biscuit manufacturer (he invented the digestive biscuit) and philanthropist Sir Alexander Grant donated £50,000 towards the cost of a new facility, which had strong similarities to the buildings housing the engineers and zoologists. The building was officially opened on the same day as the Sanderson Building: 28 January 1932.

An image from 1919, showing the YMCA hut in St Andrew’s Square, prior to its purchase and relocation at KB.

A new emphasis on health

The Great War had led to millions of military and civilian casualties, a societal shock made greater by the severity of the subsequent global influenza pandemic. In the following decade there was an increased public emphasis on health and welfare, which was reflected in the actions of institutions such as the University. One immediate consequence was the construction of new sports and athletics facilities in the city, and King’s Buildings benefited by the opening of new tennis courts (which can be seen in the photograph below) and a hockey and football pitch, all of which would be part of the campus until the mid-1970s. The following paragraph from a University pamphlet is curiously resonant today:

“In 1930 authority was obtained by Ordinance to charge an additional half guinea to the annual matriculation fee, the money so obtained being devoted to the physical welfare of the students. All students are now entitled to free medical examination and are given advice regarding suitable exercises.”

From ‘A History of The University of Edinburgh, 1883–1933’

In this 1931 image, the Institute for Animal Genetics (now the Crew) is complete, along with its animal outbuildings and a 30-acre farm. The Engineering and Geology buildings are under construction, with the Geology structure eating its way into the temporary YMCA hut. Some of the tennis courts are already in use.

King’s Buildings in 1932: no future?

Donations from individuals and foundations were crucial to this period of campus development and led to the construction of some of its finest buildings. But such methods of financing were highly dependent on a buoyant economy, and the economic depression in the 1930s brought much of the construction at King’s Buildings, and across the wider University, to a temporary halt. In addition, there had been many powerful voices within the University who were raising objections to any further extension of the campus.

The scattering of departments from the University’s core at the heart of the city had caused some anxiety (the ‘centrifugal effect’), and by the late 1920s there were already calls for the ‘reintegration’ of the University’s various parts, voices that became louder as the new decade began.

In 1931 the architect and planner Frank Mears was able to say that George Square was “rapidly becoming a university campus”. The ‘Mears Report’ on the development of the wider area around the University featured grand plans for urban regeneration, involving an orientation of institutional buildings along a pair of east-west axes to form avenues of academic and related buildings – his ‘College Mile’. Inherent in Mears’ proposal was the conviction, shared by many in the city, that the gradual transfer of academic departments to King’s Buildings should be halted, and, with a few special exceptions, reversed.

By 1932, therefore – only ten years after the Chemistry Building had opened – the future of The King’s Buildings was by no means certain…

Peter Reid, College of Science and Engineering

We are indebted to the following sources of information for this brief history:

- “Science at the University of Edinburgh 1583–1993”, Birse;

- “Building Knowledge: an Architectural History of the University of Edinburgh”, Haynes & Fenton;

- “The University of Edinburgh: an Illustrated History”, Anderson, Lynch & Phillipson;

- the collected notes of Des Truman, and many other College and University sources.

Recent comments