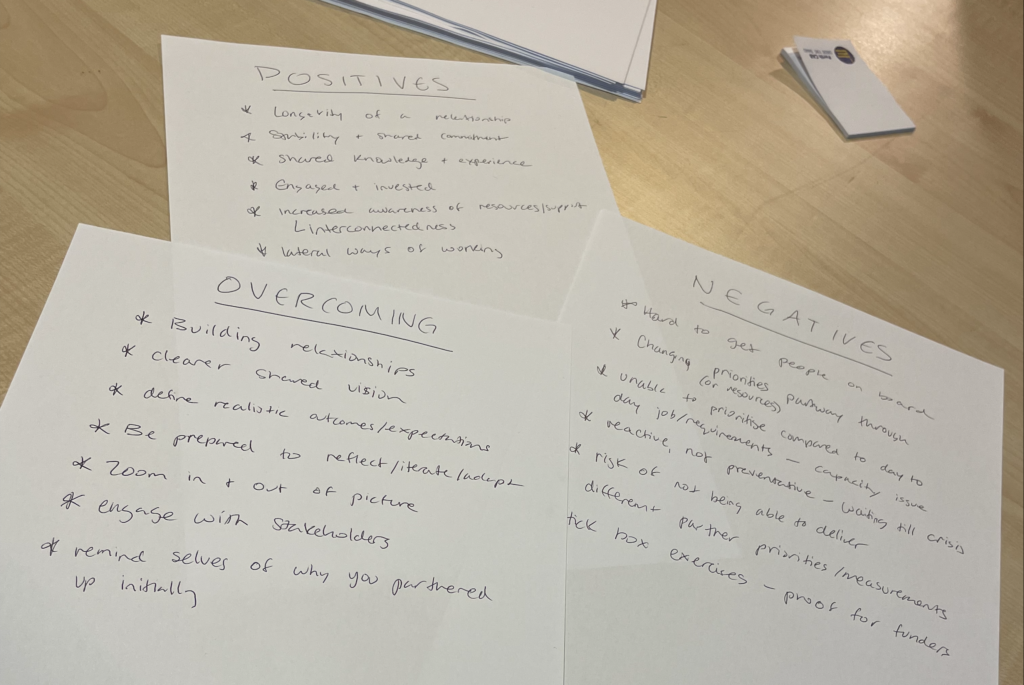

As part of PerthCAB’s Cultivating Collaboration and Change Conference, I had the chance to be part of a workshop about Effective Partnerships, which involved an exercise where we were asked to discuss and document three things around our experiences in partnerships:

- What works well?

- What are the challenges?

- What ways have you managed to overcome them?

My table reflected upon the various partnerships they’d experienced. Although there were clearly certain functional components to a partnership that would either help or hinder its success, the focus quickly became more about the feelings that surrounded their structure, rather than the structure itself. Our ‘Positives’ list reflected the idealism around a partnership – the reason they get created in the first place and the potential that they have to offer. Whereas our ‘Negatives’ list encompassed the harsher reality of obstacles and challenges that are often faced, particularly with partnerships operating outside of the ‘day to day’ responsibilities of a job. These are two sides of the same coin, and often the actual circumstances aren’t changeable. However, we then found that our ‘Overcoming’ list was representative of behavioural or perceptive shifts. Not necessarily adjusting the circumstances themselves, but rather the way that you move through them.

As someone who’s entire role revolves around a partnership, I found this workshop invaluable. I recognised that I’m still in the perspective and experience of a fresh start. Yet to face inevitable obstacles, and filled with the potential of bringing expertise and experience together to explore complex issues. Throughout this project, it will be important for me to find balance in between the two, and continual assess and adapt my own and my collaborators ways of working in order to do so.