Two unquestionably essential sources for any researcher interested in the history of Islamic Egypt are al-Kindī’s Kitāb al-Wulāt wa-Quḍāt and al-Maqrīzī’s Khiṭaṭ.

al-Kindī and al-Maqrīzī

Al-Kindī, or Abū ʿUmar Muḥammad b. Yūsuf al-Kindī al-Tujībī (283-350/897-961), was an Egyptian historian who lived during the Ikhshidid rule over Egypt. He was born into the Tujīb clan, a group originating in southern Arabia that settled in al-Fusṭāṭ, very likely at the time of the conquest. We know little about his life, but apparently, two of his ancestors held positions in the military administration of Egypt in the first two centuries of Islam. Most of his works are lost, except for Kitāb al-Qudāt and Tasmiyat Wulāt Miṣr or Umarāʾ Miṣr (the first title is the one used in the manuscript kept at the British Library, while the second title is how the book is known by those who quote it).

The Tasmiyat Wulāt Miṣr is less a biographical work and more, as S. Bouderbala puts it, “a summary of the Egyptian administrative history.” The organisation of the work is chronological, following the offices. Each section begins with the name of the governor, dates of appointment and arrival in Egypt, who appointed him, and specifics about his offices (ṣalāt and kharāj or only ṣalāt). Then the delegates are enumerated. The rest of the section consists of events that took place during the office and involved the governor in one way or another and/or decisions taken by him during his office. From time to time, some verses of poetry are inserted.

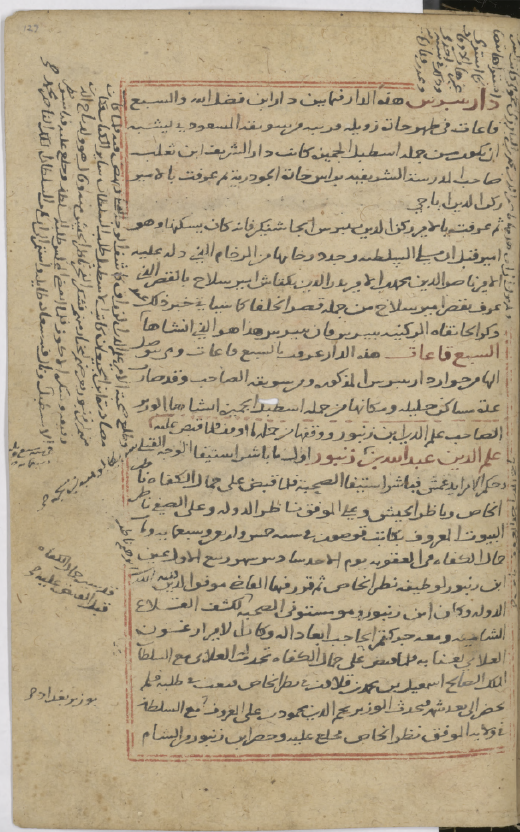

Page of the manuscript Ms Add 23 324 kept at the British Library, with mention of the title, first line

The Kitāb al-Wulāt, as well as other works of al-Kindī, are used by Mamluk historians up to al-Suyūṭī. Al-Kindī is notably quoted by al-Maqrīzī in Khiṭaṭ for the pre-Tulunid period and by Ibn Taghri Birdi in Nujūm.

The reuse of al-Kindī’s Wulāt by al-Maqrīzī in al-Mawāʿiz wa-l-iʿtibār fī dhikr al-Khiṭaṭ wa-l-athār, better known as al-Khiṭaṭ, is clearly evidenced with the tools developed by the KITAB project, PASSIM in particular :

A visualisation comparing al-Kindī’s “Wulāt” on the top with Al-Maqrīzī’s “Khiṭaṭ” on the bottom. Yellow lines indicate reused text, and the red bars show the length of each instance of reuse.

Al-Maqrīzī (766/1364-65;845/1442) was a historian born in Egypt who lived during the Mamluk Sultanate. He held various administrative offices, from deputy judge and administrator of endowments to secretary and muḥtaṣib in Cairo. After 1412, he devoted his time to writing, and among the thirty titles attributed to him, “al-Khiṭaṭ” is his major project. Described as “a veritable Encyclopaedia of the heritage of Cairo” (Bauden, XX), this work is a significant contribution to the history and topography of Egypt, especially Cairo.

Fiscal Revolts in Abbasid Egypt in Khiṭaṭ

When I began investigating fiscal revolts in Egypt, after noticing their frequent mention by al-Kindī, I looked for additional sources on these events. Unsurprisingly, Ibn Taghri Birdi and al-Maqrīzī also mentioned these events in their works, relying on al-Kindī.

What I found particularly interesting in the case of al-Maqrīzī is that he gathers episodes of fiscal uprisings in his first volume, in a chapter devoted to the Arabs of the Delta, entitled “How the Arabs Settled in the Egyptian Countryside and Took up Agriculture and What Happened in the Process.” This chapter immediately follows the one about “The Rebellion of the Copts and How it All Happened,” where several fiscal revolts (725, 739, 767, 773, and 831) are recorded. In the chapter on the Arabs in the Delta, al-Maqrīzī gathers scattered accounts from al-Kindī’s work about the Arabs, from their settlement in the Delta to their uprising in the 830s. Interestingly, the only uprising not mentioned is the first one of 785.

The revolt of 785 marks a significant point in the history of fiscal insurrection in Egypt, particularly as the first large-scale Arab fiscal revolt in the Delta. Yet, al-Maqrīzī omits it in this chapter, and this absence, intentional or not, warrants further investigation. Additionally, it is notable that the last revolt recorded by al-Maqrīzī is the episode in the 830s. His chapter ends after al-Ma’mūn’s journey to Egypt, with an anecdote involving fiscal components, as if the revolts following the 830s were not about taxation anymore.

Examples of al-Maqrīzī’s historian practices

To observe how al-Maqrīzī worked with al-Kindī’s material, let’s consider two instances of fiscal revolts that occurred during the long caliphate of Hārūn al-Rashīd (786-809):

- First revolt: In 178/794-795 (Autumn of 793), the governor and finance director Isḥāq b. Sulaymān is said to have increased taxes, leading to a revolt in the Delta. He sent troops but was defeated. After reaching out to the Caliph, the latter sent the commander Harthama b. Aʿyān and his troops to suppress the revolt. The outcome suggests that control was imposed and taxes were paid, although the mode of resolution (battle or negotiation) is not explicit.

- Second revolt: In 191-192/807-808, two governors, al-Husayn b. Jamīl and then Mālik b. Dalham, had to deal with uprisings in the Delta and on the roads between Egypt and Syria-Palestine. The Caliph sent Yaḥyā b. Muʿadh to address the situation, which took about ten months. The leaders were arrested and prisoners sent to Baghdad.

These two examples are particularly suited for such observation since they present different layouts in al-Kindī’s work. The first revolt is described in a few lines, while the second is longer, mentioned in the entries of two governors with verses of poetry and more details.

To display al-Maqrīzī’s use of Wulāt material for these revolts, I use a convenient application developed as part of the KITAB project: The Diff Viewer.

“An application that allows you to see the differences between two related pieces of text. It is used primarily to read passim outputs, but it can be used with any two (relatively short) pieces of related text”.

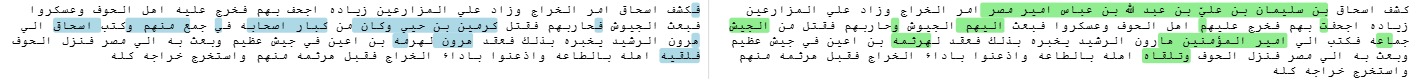

First revolt

What is not highlighted consists of what is common between both texts, covering most of the account. The nature of the differences between both accounts is easy to understand and explain:

- First difference:

- Al-Kindī writes: فكشف اسحاق امر الخراج, while al-Maqrīzī gives: كشف إسحاق بن سليمان بن عليّ بن عبد الله بن عباس أمير مصر أمر الخ

- In other words, where al-Kindī only gives the ism of Isḥāq, al-Maqrīzī provides the entire name “Isḥāq b. Sulaymān b. ʿAli b. Abdallāh b. ʿAbbās” and clarifies his capacity as “amīr Miṣr” = “governor of Egypt.”

- In al-Kindī’s work, the mention of this revolt appears in a longer entry devoted to the governor Isḥāq b. Sulaymān, making extra details unnecessary, as his name and position are already mentioned. Al-Maqrīzī, extracting sentences for his chapter on the Arabs of the Delta, needs to provide context about Isḥāq for his readers.

- Second difference:

- When mentioning those who died in the battle between the jund and the Ahl al-Ḥawf, al-Kindī specifies a name: فحاربهم فقتل كرمين بن حيى وكان من كبار اصحابه في جمع منهم

- Al-Maqrīzī is more allusive, writing: وحاربهم فقتل من الجيش جماعة

- In contrast to the first difference, al-Maqrīzī provides fewer details about who died because this information might not have been important for his readers. He only mentions that people from the army died, focusing instead on the Arabs of the Hawf, the subject of his chapter.

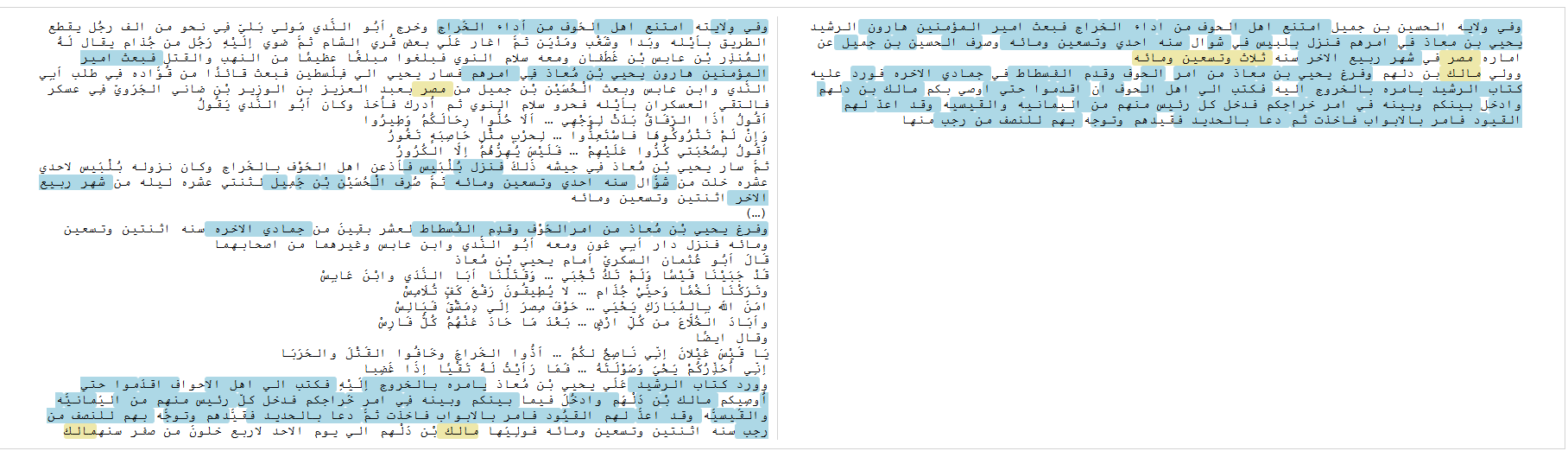

Second revolt

In the right column, you find the paragraphs devoted to the revolt in al-Kindī’s Wulāt, excerpted from the entries of two governors who succeeded each other, al-Ḥusayn b. Jamīl and Mālik b. Dalham. In the left column is the paragraph about the same revolt in al-Maqrīzī’s work. What is underlined in blue is the common text, and in yellow, the same text in different positions.

- The differences can be easily explained and reveal elements of al-Maqrīzī’s quotation practices. It is clear that al-Maqrīzī reuses al-Kindī‘s text, relying entirely on it. However, he significantly shortens the account by excluding all the verses of poetry quoted by al-Kindī, possibly considering them unnecessary for his chapter.

- Another difference is that al-Maqrīzī omits any mention of highway robbery, found at the start of al-Kindī’s account: وخرج اَبُو النَّدي مَولي بَليّ فِي نحو من الف رجُل يقطع الطريق باَيْله وبَدا وشَغْب ومَدْيَن ثمَّ اغار عَلَي بعض قُري الشام ثمَّ ضوي اِلَيْهِ رَجُل من جُذام يقال لَهُ المُنذِر بْن عابس بْن غَطَفان ومعه سلام النوي فبلغوا مبلغًا عظيمًا من النهب والقتل

- Names are also removed. Similarly to what we observed previously, al-Maqrīzī clarifies that the revolt started during al-Ḥusayn b. Jamīl’s governorship, while in al-Kindī, this clarification is unnecessary as it appears in his biographical entry.

These examples show that the reuse of historical information from one author to another is not merely copy-pasting. Quotation practices must be considered within the broader context of historical composition. In these examples, al-Maqrīzī made intentional modifications to al-Kindī’s text, aiming for clarification, summarisation, or refocusing, depending on the chapter’s topic where he gathered these scattered accounts about fiscal revolts.

Banner Image: fol. 129 of the holograph fair copy of the third volume of al-Maqrīzī’s Khiṭaṭ held in the Library of Michigan University (Michigan Islamic MS 605). https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015079127406 . About this manuscript; Bauden, Frédéric & Gardiner, Noah. (2011). A Recently Discovered Holograph Fair Copy of al-Maqrīzī’s al-Mawāiz wa-al-itibār fī dhikr al-khitat wa-al-āthār (Michigan Islamic MS 605). Journal of Islamic Manuscripts. 2. 123-131. 10.1163/187846411X593445.

This blogpost has been written by Noëmie Lucas.

Leave a Reply