As part of my research on the Caliphal Finances project, I (PostDoc Noëmie Lucas) am studying tax revolts that occurred repeatedly in Egypt from the Marwanid period to the second half of the ninth century. My focus is particularly on the narrative perceptions of these revolts. In this blog, I revisit the revolt that occurred in 168/785 in the Eastern Delta, on which I delivered a lecture for the SCORE Lecture Series, to illustrate an example of dissonant perceptions of the same event.

The revolt under discussion took place in the Eastern Delta in 168/785, during the final year of al-Mahdī’s caliphate (158-168/775-785) and under the governorship of Mūsā b. Muṣʿab over Egypt (167-168/784-785). This event is considered the “first large-scale Arab fiscal insurrection in the Delta” (Bouderbala, 2024). In this blog, I analyze two narrative sources: the Kitāb al-Wulāt by al-Kindī and the Taʿrīkh by al-Ya’qūbī.

The Sources: Al-Kindī and Al-Ya’qūbī

The longest account of the 168/785 revolt is found in one of the two preserved works of Abū ʿUmar Muḥammad b. Yūsuf al-Kindī al-Tujībī (283-350/897-961), Tasmiyat wulāt/umarāʿ Miṣr (commonly referred to as the Kitāb al-Wulāt, or The Book of Governors). Al-Kindī’s other surviving work is Kitāb al-Quẓāt (The Book of Judges). Al-Kindī, an Egyptian historian of the Ikhshidid period (935-969), provides much of what we know about the Arabs in the Delta (Ahl al-Ḥawf) and their uprisings during the early Abbasid rule.

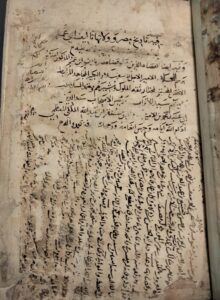

MS Add 23 324. “ Kitab Wulat Misr, a History of the Governors of Egypt from the Arab conquest to AH 335 by Abu Umar Muhammad Ibn Yusuf al-Kindi. Kitab Kudat Misr, a History of the Judges of Egypt from the Conquest to AH 246 by the same. Arabic. AH 624, AD 1227. 4 Cat, p. 550 b.”

The revolt is also mentioned in the Taʿrīkh (History) of al-Ya’qūbī, a ninth-century historian who spent time in Egypt and witnessed the fall of the Tulunids. His work frequently records Egyptian uprisings, though with notable differences in tone and emphasis compared to al-Kindī.

The Accounts of the Revolt

Al-Kindī’s Account

In al-Kindī’s Kitāb al-Wulāt, the revolt in the Eastern Delta is contextualized within the governorate of Mūsā b. Muṣʿab. Al-Kindī’s chapter is not primarily focused on the revolt but rather on the unpopularity of Mūsā, whose taxation policies are portrayed as symptomatic of illegitimate rule. Al-Kindī’s narrative legitimizes the actions of the Ahl al-Ḥawf and the jund by framing their opposition as a reaction to Mūsā’s oppressive governance. The account culminates in the killing of Mūsā during a battle between the Ahl al-Ḥawf and the jund, an outcome presented as a justified consequence of his unjust rule.

| Roadmap of the account in al-Kindī’s Kitāb al-Wulāt | |

| 1 | Arrival of Mūsā in Egypt and actions against the previous governor (p. 124 l. 15- p. 125 l. 5) |

| 2 | Actions of Mūsā in Egypt (p. 125 l. 6-8)

|

| 3 | Verses of poetry (p. 125 l. 8-10) |

| 4 | Hatred of the jund and the Ahl al-Ḥawf against Mūsā and Alliance(s) p. 125 l. 11 –p. 126 l. 3 |

| 5 | Mūsā’s orders against Diḥya’s revolt in Upper Egypt and the actors involved (p. 126 l. 3-11) |

| 6 | “Battle” between Mūsā and his army and the Ahl al-Ḥawf

Retreat of the jund and killing of Mūsā “Then they travelled until they reached al-ʿUrīrā and the Ahl al-Ḥawf attacked them, and among them were Yaman and Qays. And when they lined up and the battle between them was about to break out, the Ahl al-Miṣr retreated, gathered and left Mūsā b. Muṣʿab. He remained with a small group with whom he had moved and no one from the Ahl al-Miṣr stuck with him except Khālid b. Yazīd b. Ismaʿīl al-Tujībī, his general and ally. Mūsā b. Muṣʿab was killed and the one who killed him was Mahdī b. Ziyād al-Mahrī. Then the Ahl al-Miṣr went back to al-Fusṭāṭ. None of them were injured. The news of the killing of Musa reached al-Mahdī.” (p. 126 l. 11-p. 127 l. 1) |

| 7 | Reaction of al-Mahdī (p. 127 l. 1-4): He swore that he would be struck off the record of the Abbasid family if he did not severely punish Mahdī, Mūsā’s killer and if he did not punish the Ahl al-Ḥawf but the caliph died before he could do so. |

| 8 | Poem composed by Ibn ʿUfayr (p. 127 l. 5-13) |

| 9 | About Khālid b. Yazīd b. Ismaʿīl al-Tujībī, general of Mūsā that was killed with him (p. 127 l. 14-17) |

| 10 | The position of the Egyptian scholar of prophetic traditons al-Layth b. Saʿd about Mūsā (p. 127 l. 18 – p. 128 l.)

Ibn Qudayd told me according to Abī Naṣr Aḥmad b. Sāliḥ, according to ʿAlī b. Maʿbad, according to Saʿīd b. Abī Maryam: I heard Al-Layth b. Saʿd while Mūsā b. Muṣʿab was delivering a speech to the people, and while he was oppressive and unjust, then Mūsā continued with this verse: (from the Surat al-Kahf,verse29): “We have prepared for disbelievers Fire whose flames enclosed them”. And Al-Layth said while Mūsā performed the speech: God do not despise us/ اللهُمّ لَا تَمقُتْنا |

Al-Kindī emphasizes the Egyptian perspective by naming the individuals involved at each stage of the conflict, highlighting the collective disapproval of Mūsā among Egyptian elites. However, we must question whether Mūsā’s unpopularity reflects factual misconduct or is shaped by the narrative’s intent to critique illegitimate governance. This hypothesis aligns with broader observations about the divergence between narrative sources and documentary evidence for other governors. For example, Qurra b. Sharīk (90/708-96/714) is portrayed in narratives as a tyrannical governor akin to al-Ḥajjāj b. Yūsuf, yet papyrological evidence depicts him as a fair administrator concerned with justice. Similarly, al-Kindī’s account may reveal more about contemporary perceptions of governance than about Mūsā’s actual conduct.

Al-Ya’qūbī’s Account

Al-Ya’qūbī’s Taʿrīkh offers a concise account of the revolt (Ya’qūbī, Taʿrīkh, ed. M. Th. Houtsma, Leiden, Brill, 1883, vol. 2, 483; trans. p. 1144):

The people of al-Ḥawf in Egypt rebelled in the year 168. Mūsā b. Muṣʿab, then governor of the province, marched against them and engaged them in fierce fighting. His standard-bearer, Hāshim b. ʿAbd al-Raḥmān b. Muʿāwiya b. Ḥudayj al-Sakūnī, lowered the standard, signalling defeat. The people of al-Ḥawf turned on Mūsā b. Muṣʿab and killed him. Al-Mahdī appointed al-Faẓl b. Ṣāliḥ al-Hāshimī, who did not arrive in the province until after the death of al-Mahdī.

While the basic facts align with al-Kindī’s account, al-Ya’qūbī’s narrative stands out for its omissions. It does not mention the alliance between the Ahl al-Ḥawf and the Egyptian jund or provide any details about the causes of the revolt. By presenting the revolt as a violent uprising without context, al-Ya’qūbī’s account implicitly condemns the Ahl al-Ḥawf and aligns with an imperial perspective. This contrasts sharply with al-Kindī’s effort to contextualize the revolt within broader discussions of just and unjust rule.

Conclusion

The dissonant perceptions of the 168/785 tax revolt in the Eastern Delta reflect differing narrative priorities. Al-Kindī’s Egyptian-centric account emphasizes local grievances and critiques of governance, legitimizing the actions of the Ahl al-Ḥawf and the jund. In contrast, al-Ya’qūbī’s imperial perspective omits local alliances and grievances, framing the revolt as an illegitimate insurrection. These contrasting narratives offer valuable insights into how regional and caliphal perspectives shaped historical accounts of fiscal revolts in early Islamic Egypt.

Banner Image: Village on the Nile (1900-1920). Henri Duval. Photo reproduced by A. Cintract (1854-1954)for the Société de géographie. http://catalogue.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb42669871x

This post has been written by Noëmie Lucas.

Leave a Reply