This series of interviews shines a spotlight on researchers working on or with the Caliphal Finances project. Each interview showcases the variety of scholarship connected to our project’s research. This week, we feature Hannah-Lena Hagemann, PI of the Social Contexts of Rebellion in the Early Islamic Period (SCORE) Emmy Noether research group at the University of Hamburg, with whom the Caliphal Finances team has been in conversation for several years. (To learn more about our collaboration, see, for example, the Trouble with Taxation workshop.)

Could you tell us about your background and career path?

I’m from Hamburg, Germany’s second largest city, and a proud northerner (come visit us – Bavaria is overrated! J). I’ve always had very broad interests and when I finished school in 2003, I struggled to decide what I wanted to study, so I took a year off during which I worked at a youth centre in what was then one of the city’s somewhat more deprived areas. That year was really helpful in letting me think about what I did and – even more importantly – did not want to do with my life. I’d briefly entertained studying law, psychology, or literature, but then I stumbled across Islamic Studies in a catalogue of humanities subjects offered by German universities and haven’t looked back since.

Over time I’ve become so annoyed with people asking me, in this really incredulous way, why I went for Islamic Studies that I started telling them it’s because of my love for Near Eastern food (which, as those who know me can attest to, is both long-standing and bordering on the excessive), but really the main reason why I chose this subject as my major was because of its incredible breadth. It allowed me to study, all in one, the history, art, and politics, language, literature, and law of a religious tradition and civilisation that at the time – two years after 9/11 – was talked about with much fear and little knowledge. I started university in 2004 and decided to remain in Hamburg for my studies: the Department of Near Eastern Studies back then and still today is one of the largest in the German-speaking realm and offers an excellent research and study environment. From 2006-2007 I also spent an academic year as a Visiting Student in Oriental Studies (as it was called back then) at Oxford, where I was first introduced to UK academia and a rather different way of ‘doing’ Islamic Studies, being taught by incredible scholars like Nadia Jamil, Adam Silverstein, and Christopher Melchert. I don’t think I’d have ended up in the same place without this experience.

I received my first degree in Islamic Studies (and two minors, Religious Studies and Political Science) in 2010. By then I’d become really interested in early Islamic history, thanks primarily to a class taught by Andreas Görke, who is now Senior Lecturer in Islamic Studies at Edinburgh. This class first introduced me to the thorny issues around the sources for early Islamic history and thought, and I was hooked immediately. My MA dissertation, supervised by Andreas, was on Khārijite poetry, which I think had everyone rather bemused, but I’d attended a seminar on them in the late stages of my degree and been absolutely fascinated, especially because so little was known about them. They’ve stayed with me for the past 15 years, and I hope that my work can contribute in some small way to renewing interest in their history and place within the Islamic tradition.

Photo of Hannah-Lena Hagemann

Following my first degree, I was very lucky to receive a full PhD scholarship from the Centre for the Advanced Study of the Arab World (CASAW) in the UK, which allowed me to pursue my doctoral research at the University of Edinburgh from 2011-2014. My dissertation dealt with the portrayal of Khārijites in early Islamic historical writing and was supervised by Andrew Marsham (now at Cambridge) and Andreas, who got his position at Edinburgh just a few months after I started there – serendipity! I submitted the dissertation in December 2014 but by then I’d already moved back to Hamburg, having begun work as a research associate in the ERC project ‘The Early Islamic Empire at Work’ led by Stefan Heidemann in May of that year, a position I held until 2019. My work within that project focused on the administrative history and geography of the province al-Jazīra (Northern Mesopotamia), one of the regions within the early Islamicate world that retained its Christian majority well past the 10th century CE and so constitutes a particularly interesting case study for the development of early Islamic state structures and Muslim/non-Muslim interaction. Oh, and it was also a hotbed of Khārijite activity, so doubly exciting!

What is your current role, and what does it involve?

Since April 2020 I’ve been PI of my own research group, which investigates rebellion in the early Islamic period from a social-historical perspective and is funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG; Emmy Noether grant 437229168). The project is entitled ‘Social Contexts of Rebellion in the Early Islamic Period’ and comprises four team members (myself included). Each of us studies a particular ‘category’ or group of revolts and rebels; my own research focuses on Khārijite rebellion (surprise!), the other three sub-projects focus on Zaydīs, Armenians, and tribal notables (ashrāf). The idea is to step away from explanatory paradigms that turn on religious identity (‘heretical’ (Shīʿī, Khārijī, Ibāḍī) or non/anti-Muslim resistance to ‘mainstream’ or ‘foreign’ religion and society), which have dominated the surprisingly limited scholarship on contention in this period, in favour of considering religion just one of many markers of identity and triggers of action. While we do not disregard religion entirely, our work seeks to explore the socio-political and socio-economic contexts of rebellion in a variety of ways: by studying tribal and geographical distribution, fiscal policies, and elite competition over resources and social status, among other factors. Crucially, we do not consider ‘Muslim’ and ‘non-Muslim’ uprisings as separate phenomena a priori but have found it more fruitful to consider them as interconnected phenomena on the broad spectrum of early Islamicate political culture. The Armenian notables who raised a number of revolts in the 8th century CE, for instance, were acting not just as local but also as imperial elites, providing military service and collecting taxes for the caliphal regime; their grievances were similar to those of their Arab-Muslim elite counterparts, and they responded in similar ways.

Apart from my research, I also teach at the department and supervise BA and MA students. I mainly offer courses that deal with pre-modern Islamic history and thought, but also touch on the modern period. I’m particularly interested in conveying to students the diversity of Islam as a religious tradition and civilisation, so I teach courses on Ibāḍism and Shīʿism, for instance. The Ibāḍī course I co-designed with my brilliant colleague Antonia Bosanquet (now at Utrecht); it’s really fun to teach and students seem to appreciate engaging with what is often portrayed as ‘marginal’ (in every sense) to ‘mainstream’ Islam. My course on Islamic ritual and practice has an almost exclusively modern focus, but again diversity takes centre stage in discussing Sunnī, Shīʿī and Ibāḍī as well as canonical (the five pillars) and non-canonical (e.g., mawlid) rituals as equally valid expressions of ‘being Muslim’.

What sources do you typically use in your research? What are their strengths, and what challenges do you face when using them for historical research?

My main sources are literary (as opposed to documentary) works in Arabic from the early and classical period, i.e. I chiefly use works that were put into writing between the 8th-14th century CE. In terms of ‘genre’ (a difficult term but not something to go into here), I focus primarily on chronicles, local histories, biographical dictionaries, and geographical literature, but also utilise legal works, adab, and (with great caution) heresiography. Generally, I try to consider all potentially fruitful material, which also includes non-Muslim works and material culture, of course.

Prosopographical analysis is a particularly valuable tool for our research group because of the immense richness of biographical and genealogical data preserved by the early Arabic tradition, which allows us to investigate networks and structures (recruitment, mobilisation, loyalties) in sometimes astonishing detail. Matrilineal and marital ties are among the most fruitful aspects here: in political chronicles or local histories, they are often disregarded in favour of narratives of ‘great men’, which is unfortunate as such ties allow us to get a much better grasp of how society worked, how and why loyalties were formed and broken, and what networks of support potential rebels could fall back on. Likewise, prosopography enables us to transcend individual contexts and events and to study long-term patterns and developments, e.g., when investigating the factors involved in creating ‘career rebels’, people who turn up in several different revolts among highly diverse rebel constituencies.

“Dirham minted in the name of the Khārijite leader Qaṭarī b. al-Fujā’a. The mint is Bīshāpūr in Fārs (southwest Iran), the mint year is 75/694-5. The obverse text (centre) has a Pahlavi inscription that claims the caliphate for Qaṭarī: ‘Abd Allāh Qaṭarī amīr al-mu’minīn (‘the servant of God, Qaṭarī, Commander of the Belivers’). The observe margin (in Arabic) reads lā ḥukma illā li-llāh (‘no judgment save God’s’), the famous Khārijite slogan.”

Beyond literary works, documentary sources – and coins especially – are an important source for me and my team. The study of rebel coinage can be extremely helpful in clarifying timelines, geographical contexts, claims made, and people involved, as well as allowing us to speculate on degrees of integration with local economies. Coins cannot tell us full stories, they do not really give us ‘hows’ and ‘whys’, but unlike the literary sources they are contemporaneous to events and so serve as important companions to and correctors of the written sources.

The challenges inherent in working with the early Islamic written sources are well known: they are late, fragmented, biased, and were subject to numerous rounds of aural editing. The situation is similar concerning non-Muslim sources, but again here we actually have works contemporaneous to the events of the first century or so of Islamic history, which is why Syriac and Armenian works, for instance, are another important source corpus that I and we use. Moreover, the Islamic sources do not often report on the activities of non-Muslims, and so non-Muslim sources provide essential insight into community affairs and relations with Muslim actors, which is vital for understanding the dynamics of mixed Muslim/non-Muslim revolts, for example. Unfortunately, the extremely rich papyrological evidence that scholars have increasingly brought to bear on the early Islamic history of Egypt in particular is less helpful for our research: rebellion is difficult to ‘see’ in the papyri; our group specifically does not work on Egypt (or Khurāsān, another area where (significantly smaller) corpora of documents pertaining to the early Islamic period have been found); and the question/problem of Egyptian exceptionalism remains.

How do fiscal theories, practices, and institutions feature in your work? How are you approaching these topics?

We mainly encounter fiscality as a bone of contention. Most of the rebellious actors we investigate were members of the political and military elites, and as such were in almost constant competition over access to state revenues and benefits. Who got to collect taxes, how much had to be sent on to the imperial administration, who was taxed, who/what was paid from collected revenues, and related questions were hot topics that touched on state-stakeholder relations and could lead to revolt if left unresolved. For our research into the social history of early Islamicate rebellion, we’re thus very interested in fiscal policies at the imperial and provincial level, especially in policy changes over time and how these relate to the various regions and constituencies within the early Islamic Empire.

This has proven very fruitful in attaining a fuller – and sometimes quite different – contextual understanding of certain revolts. For instance, there is a persistent idea among some scholars that Khārijites were opposed to any and all non-Qur’ānic taxation: in this view, Khārijites were fine with e.g. zakāt but rejected e.g. kharāj as a human (and thus illegitimate) innovation. The historical record simply does not support this idea: many different Khārijite groups across various regions and periods in fact taxed the areas they conquered, and beyond the literary sources we also have Khārijite coins from the 7th and 8th century CE that likewise show interaction with and integration into local economies, which presumably also included taxation. I wonder whether this does not once again highlight the deceptive simplicity of confessional interpretive frameworks: Khārijites are remembered as extreme zealots violently opposed to the slightest hint of human meddling with the divine order, which in this view naturally includes taxation as well. What I hope to show in my research, however, is that it was not so much the question of whether ‘human’ taxes had to be paid at all but rather who had to pay them: several of the Khārijite clusters that I currently investigate, which were active in the late 7th and throughout the 8th century CE, seem to have been composed at least at the leadership level of tribal-military elites who in particular historical moments (each roughly two generations apart) lost out in some way: they were dropped from the military dīwān and so lost their stipends, and/or they were taxed following settlement despite belonging to the Arab-Muslim conquest elite. In their case, then, rather than rejecting taxation as a point of principle, these rebels objected to their removal from the list of tax beneficiaries. In stressing the fiscal dimension of these Khārijite revolts, we can thus arrive at a more nuanced picture that properly contextualises the uprisings against policy changes at the imperial level and takes full account of the tribal and professional specificities of these rebels, rather than explaining their discontent by virtue of their heretical zealotry.

In your opinion, what is a key argument or prevailing assumption in Islamic fiscal history that needs to be challenged?

The key paradigm that I think needs to be properly investigated is the idea of ‘tax revolts’. There is a prevailing assumption that rebellion can be explained by abusive fiscal regimes, i.e. the raising of taxes beyond a sustainable level, and while there is certainly truth to this in many contexts, it is by no means the only or often even the main reason for why people took up arms in situations of economic and fiscal pressure. What taxes exactly do we mean when we speak of ‘tax revolts’? Where was the line that separated acceptable from unacceptable tax demands? Was it always the same or did it differ according to political, economic, geographical, or climatic circumstances? Did it make a difference if taxes were raised in cash or in kind (or both)? Was resistance aimed at the material or the symbolic dimension of taxation, or both? How do we explain regional differences in the quality and quantity of ‘tax revolts’, is this a function of unevenly preserved source material or a result of substantial contextual variation? Was taxation a trigger or a cause, i.e. a short- or a long-term reason for rebellion, or perhaps both? And if it was both, how can we distinguish between cause and trigger? The list goes on.

In short, the ‘tax revolt’ paradigm has never been suitably expounded and argued for the early Islamicate context, and so for the moment much of what is being said about this remains within the realm of speculation and educated guesswork. To give but one example of how the term can obscure more complex realities, my postdoc, Alasdair Grant, shows in a freshly published piece that the Armenian revolts of 774-5 CE were instigated by changes in early ʿAbbāsid taxation policy that deprived the Armenian notables of the tax assessment and collection privileges they had enjoyed until the mid-8th century CE. The revolts that followed should thus primarily be understood as stakeholder protest against a reduction in socio-economic status, not simply as opposition to an abusive taxation regime as such. Overall, ‘fiscal revolt’ might be a more fruitful term than ‘tax revolt’, but it, too, will need to be properly theorised.

Many thanks to Hannah-Lena Hagemann for sharing her thoughts and research with us this week! To read more of these interviews with friends of the Caliphal Finances project, click here.

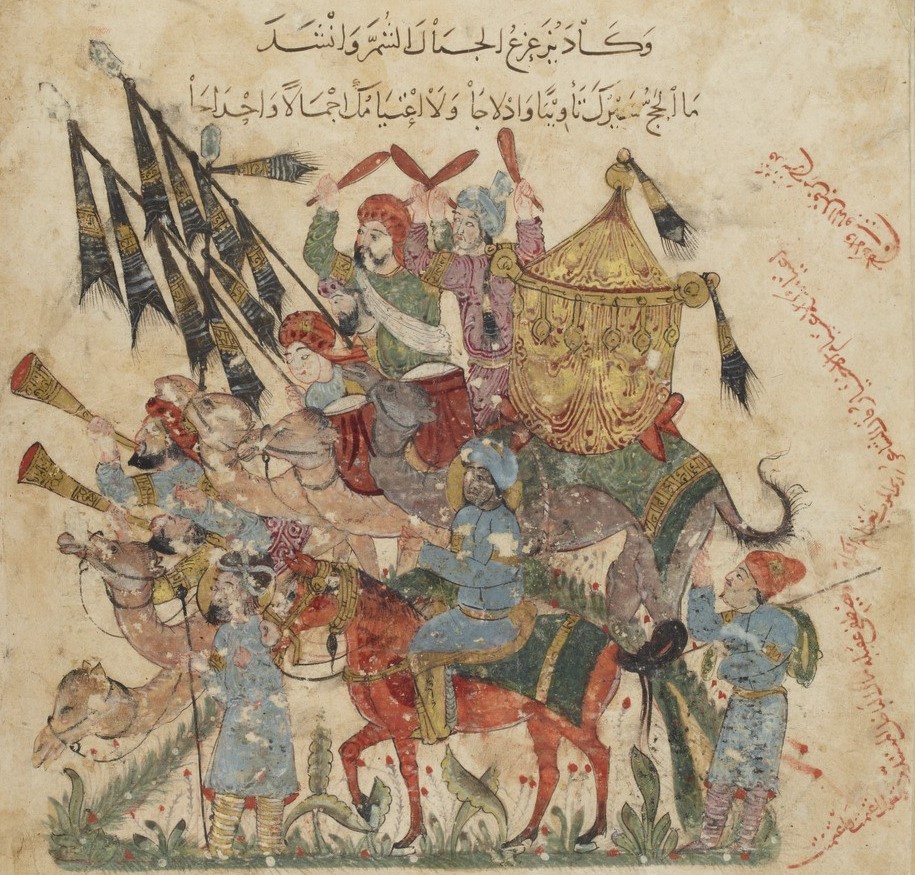

Banner Image: folio 94v from MS Arabe 5847, Les Makamat de Hariri ; exemplaire orné de peintures exécutées par Yahya ibn Mahmoud ibn Yahya ibn Aboul-Hasan ibn Kouvarriha al-Wasiti. gallica.bnf.fr, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Département des manuscrits

Leave a Reply