Week 1 | Two Anthropological Turns | Neil Mulholland

As a way of beginning to investigate the overlap between two distinct disciplines: contemporary art and anthropology, we will start from the perspective of contemporary art.

From an artistic point of view, practice is said to turn towards anthropology. This can take a number of forms. In this little resource, I will present a couple of ways that we might identify and articulate such a turn: a) Anthropological ‘subject matter’ b) The turn to ethnography.

Part 1 | Anthropological ‘subject matter’

By way of an introduction, let’s look at a few examples of artistic practice that, perhaps, encapsulate such approaches. This will provide you with some background to this week’s reading.

Art History’s exploding view of ‘culture’

In comparison with Art History’s focus on what was once called the European canon of art, early 20th century Anthropology offered a much more holistic definition of culture. Having focused disproportionately on Western art in the c19th, the discipline of Art History’s engagement with anthropology (Aby Warburg in particular c.1912) slowly ushered in more global cultural perspectives. If you want to delve into this in more depth, see:

Contemporaneously, for European artists, the increasing visibility of global artefacts expanded their conception of cultural practices and their (opportunistic) understanding of what might constitute their own artistic ‘sources’. Cultural territory that had been seen as the domain of the discipline of anthropology starts to become amenable to modernist artistic practice. Crucially, for such modernist artists, there was no fieldwork. Their understanding of anthropology/its domain was derived from what could be read and seen in European cities! We might consider this an early anthropological turn in art.

Early Modernism

In Early European Modernism we see this, infamously, in the work of Pablo Picasso following his c.1907 encounter with the world art collections of the Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro in Paris.

Pablo Picasso with Tahitian figure

This colonial trope in Picassoid modernism (primitivism) is one that has since been dissected and deconstructed, for example, recently in From Africa to the Americas: Face-to-face Picasso, Past and Present Musée des Beaux-Arts de Montréal (Quebéc, Canada) May 12- September 16, 2018 an exhibition that mixed Picasso’s work and his ‘sources’ with that of today’s contemporary artists. Both the curatorial interpretation and the contemporary artworks in the exhibition present a postcolonial critique of the colonial perspectives that are often seen as synonymous with modernism.

https://www.mbam.qc.ca/en/exhibitions/from-africa-to-the-americas-face-to-face-pica/

From Africa to the Americas: Face-to-face Picasso, Past and Present

Early Postmodernism

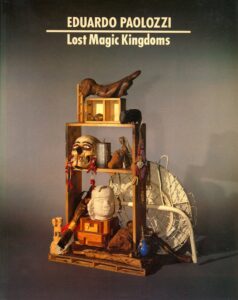

In early postmodernism, pop artists were equally enthralled by ethnographic collections, but start to see these as aligning with conducting something akin to an amateur ethnography of capitalism (‘pop art’). Objects in particular become part of a much broader quasi-fictional narrative of animate and allegorical things. Fieldwork is still largely absent here; however, there is a greater sense of parallelism and interplay between cultures (rather than straightforward cultural appropriation). A good example remains Lost Magic Kingdoms at the British Museum, 1987 curated by Edinburgh-born co-founder of the Independent Group and British pop art Eduardo Paolozzi. We might consider this to represent a second phase of the anthropological turn in art (sometimes referred to as ‘museological art’).

Eduardo Paolozzi. Lost Magic Kingdoms, Catalogue, British Museum, 1987 ISBN: 9780714115795

A small redux of Paolozzi’s Lost Magic Kingdoms was included in his Whitechapel retrospective of 2017:

Eduardo Paolozzi – Whitechapel Gallery

Late Postmodernism

Late postmodernism, like the discipline of anthropology itself, starts to interrogate the ethnocentrism of the artworld. The controversional Magiciens de la Terre at at the Centre Georges Pompidou and the Grande halle de la Villette 18 May – 14 August 1989 remains a central case study in this regard. Magiciens de la Terre tackled the anthropological turn from a nascent postcolonial perspective. This third phase of the anthropological turn in art takes place while anthropology is both decolonising and turning towards arts-based approaches (partly as a way of reviewing and decolonising its own history as a discipline).

Magiciens de la Terre, Paris 18 May – 14 August 1989

Like Lost Magic Kingdoms, this legendary exhibition has also been reduxed:

Magiciens de la terre, a look back at a legendary exhibition – Exposition documentaire

Magiciens de la terre Retour sur une exposition légendaire Centre Pompidou, Paris July 2 → September 15, 2014.

Stedelijk Studies – Revisiting Magiciens de la terre

Redux Retour

Magiciens de la terre Retour takes us full circle. What we might now think of as acts of cultural appropriation – such as Picasso openly plundering ‘African art’ – brought non-Western cultures into the orbit of art galleries (rather than reserving them within ethnographic museums). It is difficult to imagine now how a major exhibition – whether presented in a gallery or museum – could not adopt a global, postcolonial curatorial perspective.

The tendency to redux (retour) exhibitions or intense periods of artistic development (‘scenes’) such as those delineated here – part of a broader trend in exhibition studies – is one that requires artists and curators to foreground and interrogate their own biases and to change the course of how we present cultural practices in exhibitionary settings.

Art galleries do not limit themselves to exhibiting works of art: e.g. the other major exhibit at Musée des Beaux-Arts de Montréal accompanying Africa to the Americas: Face-to-face Picasso, Past and Present was on the fashion designer Thierry Mugler: Beyond Couture. Equally, ethnographic museums now commission new contemporary works of art to exhibit alongside their larger collections; an example here would be the curatorial programming of the Tropenmusuem of World Cultures in Amsterdam:

The artist-museum residency is centrally important here. It enables artists to research collections of artefacts that they were unlikely to have engaged with when they were art students. Major works of contemporary art now regularly emerge from collaborations between artists and ‘ethnographic’ museums. For example, Camile Henrot won the Silver Lion Award at the Venice Biennale in 2013 for Grosse Fatigue, a film she create during her 2013 fellowship at the Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C.

[Excerpt from Camile Henrot *Grosse Fatigue* 2013](https://vimeo.com/86174818)

Excerpt from Camile Henrot *Grosse Fatigue* 2013

Contemporary art galleries and biennale (which have not collections to look after) and museums (which do) are, thus, now both involved in programming and commissioning culture rather than collecting and/or curating pre-existing artefacts. The line between cultural production and cultural analysis – a boundary that has been more clearly demarcated in anthropology than in art – is increasingly blurred in both disciplines.

Part 2 | The turn to ethnography

Ethnography

Firstly a caveat: In his 2007 Radcliffe-Brown Lecture, renowned anthropologist Tim Ingold argued that anthropology is not ethnography. DOI:10.5871/bacad/9780197264355.003.0003 Certainly, ethnography predates modern social anthropology and, as a method, ethnography not unique to anthropology (e.g. it is equally prominent in sociology and human geography).

This particular alignment between the practices of contemporary artists and the practices of ethnographers is widely attributed to Foster, Hal. “The Artist as Ethnographer,” in The Return of the Real. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1996. You will have see that Foster’s text is a common point of reference for many of readings for Week 2.

Foster uses this analogy to cast doubt on the research practices of artists who have a particular investment in social practice and, thus, conduct ‘site-specific’ investigations and immersive social experiments that resemble ethnographic fieldwork wherein ethnographers situate or immerse themselves in everyday life of their subjects of study (participant-observation). It’s worth reading Foster’s chapter to gain his insight into the issues this raises:

Foster’s comparison risks presenting some forms of artistic practice as ‘failed ethnography’. Is this comparison fair or appropriate insofar as artistic practice is not ethnography; would we judge **ethnography to be ‘failed site-specific art’?

Artists who have formally studied anthropology frequently adapt ethnographic approaches to their own artistic ends. For an artist, ethnographic method might not be so much a shared disciplinary endeavour (‘methodocentrism‘) as a resource to be selectively ‘mined’ to form part of their distinctive approach to producing artistic-knowledge (extradisciplinarity). A good example of this is Aleksandra Mir’s Living & Loving project (2002-05) which takes an ordinary human subject as its field. Mir’s approach is unlikely to be regarded as straigforwardly ethnographic by an anthropologist, but it does borrow some its key assumptions from ethnographic method (it contains elements of fieldwork, of immersive participant-observation, focuses on rituals of everyday culture, is concerned with kinship and personhood formation, uses semi-structured interviewing techniques…)

Of course, ethnographic field work is slow, ethnographers normally spend a year or more immersed in the field. Mir’s spends only a few days perhaps. Her project shows also her growing identification with the subject; Mir doesn’t attempt to maintain an objective distance as ethnography attempts to (at least in the early 20th century).

Living & Loving

Aleksandra Mir / Polly Staple Living & Loving: The Biography of Mitchell Wright White Columns, New York ISBN: 0-9552848 / ISBN: 978-0-9552848-0-9

Auto-ethnography

While it does not focus on the artist herself, Mir’s Living & Loving project has parallels with auto-ethnography. Auto-ethnography is a hybridised method, it borrows its tactics and approaches equally from the arts and the social sciences.

Going meta

If you want to read an example of auto-ethnography that is also about auto-ethnography please read: Wall, S. (2006). An autoethnography on learning about autoethnography, International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5(2), Article 9.

In Anthropology, auto-ethnography is a self-conscious process and product grounded in personal experience. As a method, it aligns as much with literature (biography, narrative storytelling and creative nonfiction) as with social science. Like a work of postmodern fiction, auto-ethnography implicates the narrator in their own narrative – proffering stories that are value-centred rather than supposedly value free.

See: Ellis and Bochner (2000; 2004, 2006, 2011) ➡

- Ellis, C.S. and Bochner, A.P. (2000) ‘Autoethnography, personal narrative, reflexivity’ in Denzin, N.K. and Lincoln, Y.S. (eds.) Handbook of qualitative research. 2nd edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, pp.733–768.

- Ellis, C. (2004). The ethnographic i: A methodological novel about autoethnography. Walnut Creek: AltaMira Press.

- Ellis, C.S. and Bochner, A.P (2006) ‘Analyzing analytical autoethnography: An autopsy’, Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 35(4), pp.429–449. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891241606286979.

- Ellis, C.S., Adams, T.E. and Bochner, A.P. (2011) ‘Autoethnography: An overview’ Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 12(1). http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-12.1.1589.

Auto-ethnographic art?

There are two broad ways that auto-ethnography tends to surface in recent artistic practice.

The Artist-Researcher

In art, the artist-as-ethnographer of the self can act a proxy for a semi-structured investigation into working-practice. Artist-Researchers frequently present their practice as a self-conscious process, proffering personal stories of their researcher journey that are – very explicitly – value-centred. Auto-ethnography in artistic research often, then, focuses on how the artist develops their own practice. It does this by foregrounding the subjective, the personal circumstances and biases of their own artistic research. (The analogy works in reverse, an artistic process such as sketching can be used to describe autoethnography: Rambo, Carol. “Sketching as Autoethnographic Practice.” Symbolic Interaction 30, no. 4 (2007): 531-42. doi:10.1525/si.2007.30.4.531)

The Auto-auteur

In art, the auto-auteur tends to focus more on personal personhood formation. While still self-conscious, resulting works of art are more product than process focused. This approach is one that is, thus, more recognisable since it is continuous with the c19th genre of the autoportrait. Where auto-ethnography favours nonfictional storytelling, the artist-autobiographer frequently ventures into what Lauren Fournier calls autotheory (2018; 2021).

Lauren Fournier’s “Autotheory and Artist’s Video: Performing Theory, Philosophy, and Art Criticism in Canadian and Indigenous Video Art, 1968-2018” can be downloaded here.

Further Resources

Some questions to explore in your Course Blog:

- The ‘graphy’ of auto/ethnography concerns writing; the writing of ethnos (folk/cultures). This could be considered to be a linguistic bias within artistic circles (as it certainly is in the social sciences).

- What problems might the perceived writing-centrism of auto/ethnography pose for auto/ethnography itself?

- What sort of recording techniques might be added to auto/ethnography in addition to writing (‘fieldnotes’)? For example, what do sort of recording techniques do artists use when conducting research? Are any of these artistic techniques used in auto/ethnography?

- The quasi-fictional form is often used in auto-ethnography as a way of implacing the author and their own perspectives into a bigger conversational world (‘the social’). (See: Leavy, P 2015, Narrative Inquiry and Fiction‑Based Research’ in Method Meets Art, Second Edition : Arts-Based Research Practice, Guilford Publications, New York.) To what extent do artists engage with this story telling format? Are artists more likely to write using autobiographical or fictional narrators?

- How / does artistic auto-ethnography differ from anthropological auto-ethnography? Is there any significant difference or do artists simply adopt an anthropological auto-ethnographic approach and apply it to their practice?

- In what ways might artistic auto-ethnography differ from established, autobiographical, forms of artistic research that focus on the agency and experience of the artist? Are artistic research epiphanies likely to be grounded in a broader culture (intersubjective) or are they fixed in relation to their own, narrower, cultural practice (solipsistic individual experience)?

- As a social science, Anthropology would – ultimately – insist that we ground ‘solipsistic’ individual experience in social relations. Do artists who engage with auto-ethnographic approaches accept this?

- Anthropological auto-ethnography continues to develop the anthropological concern with personhood formation and how this differs between, and within, cultures. Is artistic research also investigating personhood formation? If so, what sort of assumptions does artistic research make about the personhood of the ‘artist’?

Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International Neil Mulholland 2024

![]()