Inheriting the Survey of Scottish Witchcraft Project

Hi! I’m Claire, a 4th year undergraduate studying International Relations with Quantitative Methods at the University of Edinburgh, and the latest in a long line of interns and others who’ve worked on the Survey of Scottish Witchcraft project. The data involved in this project was originally compiled in a Microsoft Access Database by academics in the early 2000’s. Since then, key information from the database has been added to Wikidata, allowing for greater accessibility as well as editing and augmentation by members of the Wikidata community. People have done lots of great things with this data, including all the visualisations put together by the previous data visualisation interns, but now that the data is stored across several different platforms, it’s important to make sure that these versions are reconciled.

My role is to find the ‘Impossible Witches’; those entries which don’t match between Wikidata and the original Access database.

Working away making my first comparisons in R. By Claire Panella, Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0

Checking against the database item by item

My initial approach to this was to use R to compare between csv files exported from the Access database, and csv files accessed by querying Wikidata. This required downloading both files, checking to make sure variable labels matched, combining the datasets, and isolating the cases where the information didn’t match iso I could look through and see where the issues were.

For some features, like gender, a lot of information has been added to Wikidata that isn’t present in the survey, but there are very few cases where Wikidata and the survey have conflicting information.

Anomalies in Gender between Wikidata and the Survey

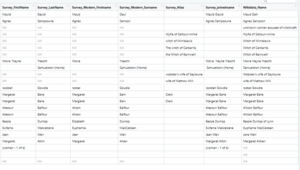

In others, like Name, the situation is a bit more complicated. Sometimes the spellings vary between Wikidata and the Survey – this could be for a few reasons, and to add to the complications, both data sources have multiple name categories – the survey includes both modern and historical first and last names, while Wikidata includes both an Item Identifier and aliases. I’ve also looked for exact matches between the text from each source, so some inconsistencies just have to do with capitalisation and spacing. Really, it’s impressive there are only 23 anomalies!

Anomalies in Name between Wikidata and the Survey

My goal now is to come up with a solid procedure to check wikidata entries against the survey so we can be sure we’re consistent and accurate in which data changes we keep. After that, I’ll work on a methodology to pass on to whomever the next ‘Witchfinder General’ is so that we can keep track of data changes as the project continues to grow and evolve.

As I look for a method to continuously check for differences between the original survey data and the most up to date version of Wikidata, I’ve turned to the Wikidata community for help. Ewan reached out to his contacts, and I reached out via Project Chat as well as a Slack channel for libraries using Wikidata. Different users have responded with various suggestions. One Wikidata user suggested a library I could use to efficiently link R with SPARQL queries, and some of Ewan’s contacts gave suggestions for the general workflow I could follow in creating a shareable methodology. One of the most helpful suggestions was that I use a tool called prompter, which would allow me to compare the results of a SPARQL query to a stable csv and store anomalies as a table on the Wikidata project page. While this looks like a great idea, it has led us to run into another of the common problems involved in working with Wikidata – not all of the tools are maintained. The Prompter tool was designed by the Every Politician Project, which was placed on indefinite pause in June 2019. This means that while the documentation for the tool still exists, it no longer works as a template in Wikidata. For me, this has been a valuable lesson on the pros and cons of working with a platform run and maintained by volunteers. Still, we are continuing to get great advice from Wikimedians around the world. A new goal of mine for the end of this project is to create a workable and well documented method that I can easily share, so I have something to give back to the community that has helped me so much throughout this project.

Leave a Reply