Overall, it has been a great couple of months for Space Exploration activities. Recovering from a quite spectacular rocket failure in early September, SpaceX was out to impress at the International Astronautical Congress in Guadalajara, Mexico, by unveiling their private plans to start colonising Mars by 2022. Space probe Juno is getting closer and closer to the gaseous atmosphere of Jupiter, ESA’s Rosetta mission came to a controlled crashing end and the first stage of another ESA’s project, ExoMars mission, has arrived to its destination.

However, in the midst of all of this excitement, little time has been given to understanding the bigger picture – why success and failure have been so abundant recently and whether the individual objectives and the collective vision for Space Exploration are being met. Of particular interest are two related streams of development: the recent almost fictional optimism of both private and governmental Space Sector players and the somewhat obvious shortcomings of their plans. Adding to this is the fact that though the two groups seem to be talking to each other, the messages pass by unreceived.

Hence, let’s take a minute for reflection and take those two issues in turn.

Potemkin’s Village on Mars

As said, Elon Musk of SpaceX announced their plans for Interplanetary Transport System for taking humans to Mars, which includes 200 “seats” per vehicle at potentially $200k ticket a-piece. However, as these plans are unpicked, there are many questions which remain to be answered and some doubts about parts of the project were already expressed, in particular on safety grounds, in addition to concerns about the validity of the business model, in particular availability of funding.

The excitement of this announcement reminded me of the initial excitement surrounding Mars One project, another colonization ambition with a commercial interest. Similar doubts were expressed then as well, though after the initial enthusiasm died down, targets were revisited and though the mission remains nominally on track it no longer occupies the centre-stage in the planning of the future of Space Exploration.

It struck me recently that these projects, often dubbed PR exercises, are perhaps more meaningful than cynical attempts at self-promotion for the individual proponents and their respective companies/organisations. And here I do not mean setting goals and establishing future trajectories as such – after all Mars has been a destination for over a century! What such “news” does, however, is setting the new norms and expectations, and the closer we are getting to actually bridge the famous gap of “Mars landing is 50 years away” the more important the content of these outlandish proposals may be.

In many ways, the success of the “news” was as guaranteed from the start as was the failure of the actual proposal – as space exploration easily catches public imagination, it is no surprise that such “news” is gets discussed in both science as well as media mainstream. But even through failure of the actual mission, the concept of space exploration gets re-defined. Most worryingly, it seems, its risk factors.

The Mars One project is a one way ticket from the onset. No return to Earth means that “survival” becomes a very relative term. If you were to die on Mars anyway, does it matter if you die on descent due to catastrophic failure of the underdeveloped or untested live support systems? If SpaceX are shipping hundreds of people to the Red Planet, does it matter if a few die en route of the radiation sickness? The somewhat cavalier attitude to such questions, recently displayed by Musk and to some extent Mars One creator, Dutch entrepreneur Bas Lansdorp, is perhaps precisely the intended effect.

If the risks of the next stage in the Space Exploration are initially presented as sky-high and brushed off as unproblematic, this could pave a way for a completely different risk perception once a much more realistic proposal from a more “down-to-Earth” consortium comes along. How better to do that than to shock the public with a radical (and unrealistic) proposal, focus on messages of hope, rather than fears or legitimate concerns and so when a still radical re-evaluation of acceptable risk comes along, it will be measured not against past standard of actual precedents, such as NASA’ Shuttle programme, where each of the fatal failures stopped all flights for years; but new benchmarks such as risks posed by some of the other more outlandish visions.

In all, this new fictional reality is far more dangerous that is seems, if accepted it assumes human life is entirely expendable in the achievement of a higher goal; if it is not accepted, then missions planned with revised risk levels might come crushing down (to Earth) if or when there is legitimate public outrage at loss of life in Space.

Jack of All Trades, Master of Luck?

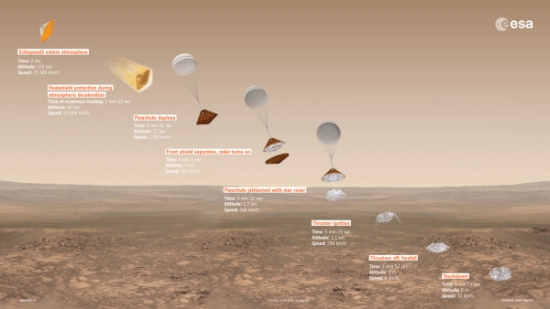

Whilst no one could accuse the European Space Agency (ESA) of lowering the standards for acceptable risk in human spaceflight, the recent ExoMars mission’s Schiaparelli lander failure is perhaps exposing another of the Space Sectors’ vices – its narrow-minded competitiveness. ExoMars’ two part mission was to insert an orbiter to study methane gas in Martian atmosphere and put a lander on the ground.

The mission is still painted as 96% success which makes one wonder if only 4% had to do with landing, why bothering to land anything at all? Perhaps, given that Schiaparelli lander was a technology demonstrator for future landing technology, its mission should be treated as 100% success – it demonstrated the current ESA landing system doesn’t work. This demonstration, however, is hardly needed. Beagle 2 (whose problem might not be crash-landing or damage from it) notwithstanding, luck, if anything, was a key element in ESA’s most successful recent mission – Rosetta – managing to land the Philae lander on the 67P comet. Harphones not firing could easily meant a fatal bounce-off the surface, but luckily the comet was a bit larger than expected, and the had a stronger gravitational pull, which resulted “only” in 1km high jump for the probe.

Yes, engineering played a significant part, too (for instance in reducing the jump by shock absorbers), and yes, most missions go wrong in one aspect or another and luck regularly “saves the day”, and another yes: the dearing of the Philae descent was truly inspirational – the fact remains that ESA’s “new norm” of combined missions (orbiter + lander) often hang on a cliff edge (or land underneath), due to technology problems, which were seemingly overcome by their counterparts.

For example, in a stark contrast to Beagle 2 and Schiaparelli lander failure, NASA has recently had four successful landings on Mars, the last one, Curiosity rover, being delivered via an automated rocket-powered sky-crane. In light of these developments, has anyone wondered why Space Agencies around the world, who cooperate on many joined projects, still prefer to develop their own parallel technology for practically every element of space exploration missions (ISS notwithstanding)?

The answer is probably – to show they can! And it is perhaps less to do with technology development and scientific advancement as such and more with proving geo-political points. Whilst the International Space Station truly leads the way in multi-faceted international collaboration, even at times when its founding partners are at loggerheads politically on Earth, many “less challenging” programmes still seem to be deeply divisive, which might be precisely the element making them less successful than they could have been.

Perhaps it is time to pause and reflect on what kind of strategy we want for the future of Space Exploration. And perhaps we should look again at the concepts of risk, safety, and international collaboration – let’s face it, in all of the excitement, we might have got them somewhat wrong.