My exciting journey with the Innovation Caucus started one rainy morning in Spring 2017, when by chance I spotted an advertisement for internship applicants doing the rounds over email. This was followed by an email from my supervisor, asking all of his PhD students if we have seen the call and whether we were interested. Not being someone who declines any opportunity, my reply was immediate – yes!

Having found out about the Innovation Caucus and its work some months previously, when putting together a notice for the departmental newsletter about our engagement with policy, I was really excited by the opportunity to further translate my research interest into useful knowledge for policy-making. Having applied and made it through to the interview, I was ecstatic! Speaking to Tim and his team was interesting and inspiring, and once I was offered the internship, it took even less time than before to say “yes” and accept it.

As I am really passionate about my PhD research topic (social aspects of technology development and innovation) and my subject matter (Space Industry – yes, the stuff “up there”) I took quite some convincing to take on new challenges within the Innovation Caucus brief. In part, this was because I really wanted to create a new space of shared knowledge and sense-making, i.e. to challenge the theoretical concepts with empirical findings and policy realities – and I could only envisage doing so within the topics about which I was already somewhat knowledgeable.

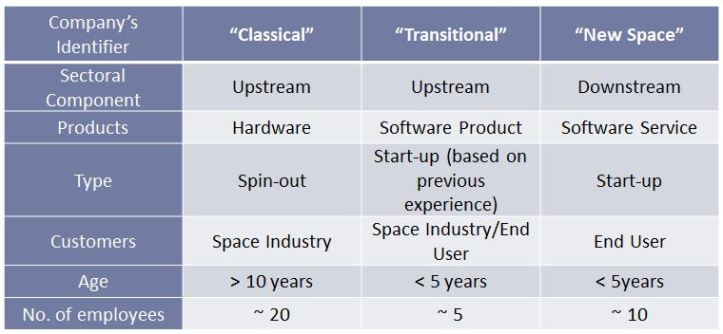

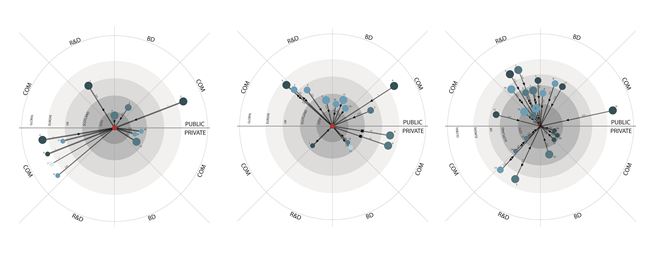

However, in discussion with Innovate UK and the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC), I did eventually reshape my interest into developing a broader framework and typology of innovation intermediation in any geographically bound sectoral system of innovation. This was of value to Innovate UK, since it supported the ongoing development of their portfolio of Catapults and Knowledge Transform Networks, as well as other projects and policies.

This experience was a great lesson for me, not only in working with and delivering for a policy-making system, but also in expanding my own research interests into domains I did initially find uncomfortable. Presenting the headline findings of this work at one of the most prestigious innovation conferences in the world, DRUID (2018), helped me appreciate the power of broader generalisation of academic knowledge, in order to achieve more substantial societal impact.

The lessons learned and experiences from this project also enabled me to engage better with new concepts, unfamiliar settings and unknown stakeholders in my subsequent work. For instance, these skills have proved critical in working on a consultancy project for the OECD and as a Research Assistant in academia.

I have to express my big thanks to Tim and his team for their support and mentorship and to all involved with the Innovation Caucus, particularly Innovate UK and the ESRC teams involved with my internship. It was your determination and generosity that turned this project from a 3-month desk-job into a transformational professional journey.

This post has been published in October 2018 at Innovation Caucus blog: Developing a framework for innovation intermediation.