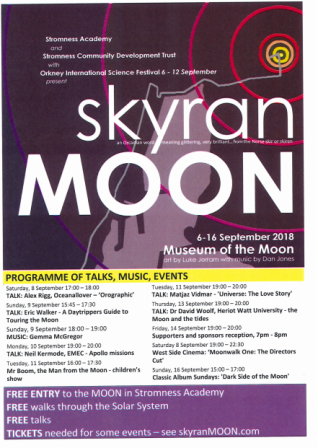

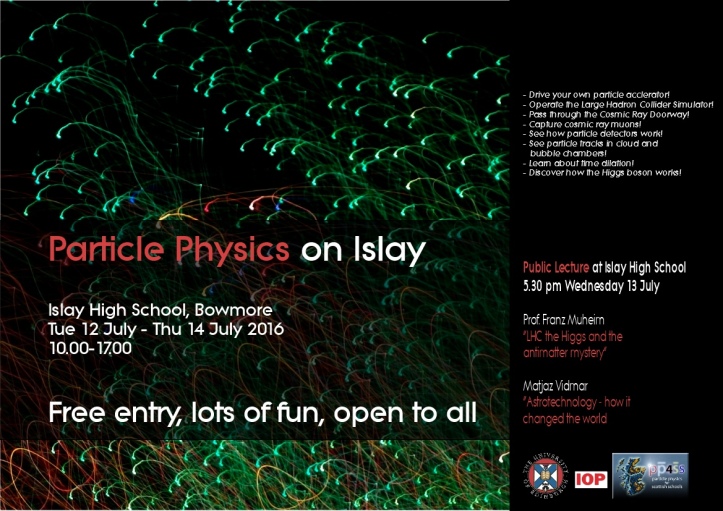

Between 25th June and 3rd July, our Space and Astronomy Tour visited North-West Scotland, in particular, the islands of Skye and Lewis and Harris as well as Sutherland and Inverness. (Here are some of the past tours to Islay, Orkney and Sutherland).

This was to continue my engagement with the Highlands and Islands communities in the context of potentially expanding space industry, which is one of my research interests at the University of Edinburgh, however, this year, in particular, the visits are also to celebrate the 200th Anniversary of the birth of astronomer Charles Piazzi Smyth (CPS200) and the 50th anniversary of the Moon landings.

As such, the programme was organised as part of the CPS200 celebrations, as well as working with the local astronomical societies Highlands Astronomical Society, Stornoway Astronomical Society and Tarbert Astronomy Group, and other groups and organisations, in particular, the local libraries and community centres and the Travelling Scholars initiative.

Over the 9 days, we travelled 875 miles in total and spent 24 hours talking to our audiences. We delivered rocket and constellation making workshops at seven primary schools (Staffin, Kilmuir, Sir E Scott, Lionel, Lochinver, Achiltibuie, Bonnar Bridge) with a total of 270 pupils and 20 teachers, as well as six evening talks (Portree, Tarbert, Stornoway, Lochinver, Lairg, Inverness) with a total audience of 102. We also held drop-in family activities at Stornoway Library, called “Rocks, Stars and Rockstar Rockets”.

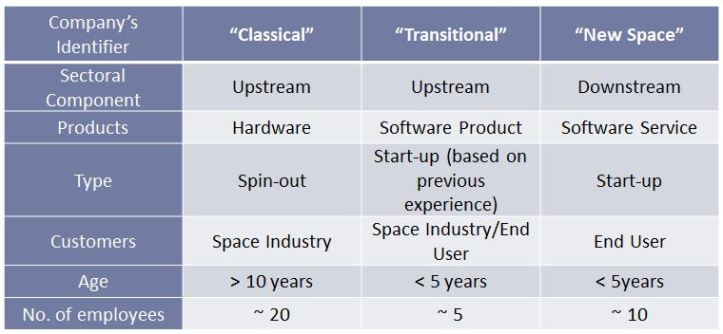

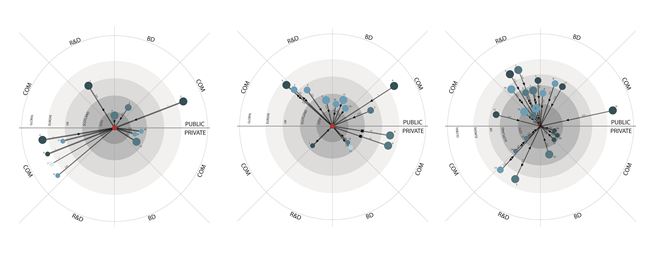

We spoke of early “astronomers” keeping time using stone circles and calendar stones, of 19th century industrial and maritime revolutions and all the way to the modern satellites, providing us with GPS, telecommunication and Earth Observation services. With several potential spaceports being planned both on the islands as well as the mainland in North-West Highlands, there was particular interest in the developments of the Scottish Space Industry, too, questions I attempted to answer as per my recent academic paper.

In all, over 100 (paper) rockets were made and successfully launched as well as over 150 (personalised) constellations. Deep questions were discussed, including what does it feel like to be inside a black hole and what might happen if we ever meet some aliens. Hopefully, fun was had by all and several promises were exchanged to visit again in the near future.

The trip was funded by IoP in Scotland Public Engagement Grant and Royal Society of Edinburgh’s Charles Piazzi Smyth 200 Anniversary Project, with generous contributions from Highlands Astronomical Society, Stornoway and Tarbert Libraries, An Lanntair Centre, High Life Highland Libraries and the Ferrycroft Visitor Centre, Davar B&B and Lochinver Community Hall, and many individuals who gave up their time to help organise and promote these events, as well as warmly embraced us with warm Highland hospitality. Thank you all!