To start building a (more) coherent picture of impact evaluation in science and technology programmes, we need to look for a constellation of many different methods to provide a meaningful insight into the need for, and success of, an intervention. Consequently, evaluation research is/should be organisational modus operandi, rather than a set of separate top-level exercises.

I propose a new paradigm in impact evaluation of investment and development in science, technology and innovation, namely Quantified Correlated Impacts (QCI). This approach is based on both quantitative as well as qualitative data collection, as bibliometric and econometric figures are correlated with ethnographic methods – interviews, focus groups and surveys – to determine the perceived causal contribution of the different factors, with particular focus on those pertaining from the intervention.

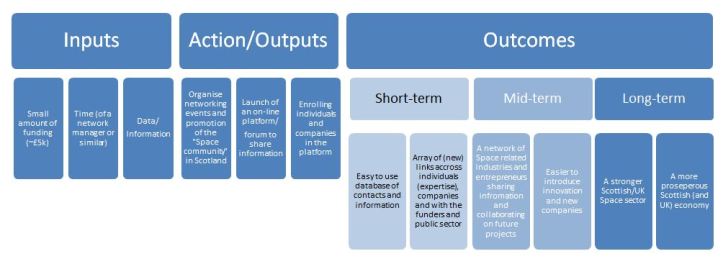

At it’s core, QCI are underpinned by a logic model; which is connecting the intervention with the evidence justifying the planned outputs; and leads form the inputs through action towards short-, mid- and long- term outcomes.

As part my research project, for example, I am involved in an intervention driving economic growth in the UK/Scotland through stimulating the collaboration across the UK/Scottish Space industry by increasing sectoral networking. This is a particularly important part of my research in business incubation in the Scottish space sector and the related (sectoral) systemic properties, such as institutional framework, networks of actors, and knowledge creation and dissemination (following Malerba’s Sectoral Systems of Innovation approach (Malerba, 2005)). Also, there is a wealth of evidence about the importance of networking for the success (and growth) of small businesses (Brüderl and Preisendörfer, 1998; Ostgaard and Birley, 1996).

The suggested action to generate these positive effects is to support the growth of small to medium sized businesses by integrating them in a wider network across the sector and wider. This will be facilitated by the creation of, and enrolment of actors into, an on-line database/forum/platform to provide easy access to contacts. Having established that, there are also provisions to host networking events (thematic or generalist), to solidify the ties and introduce more actors into the network, particularly from the non-core businesses.

In terms of evaluation, key facilities need to be established prior to the beginning of the evaluation of outputs (database and its uptake, and the networking events). The database growth can be analysed quantitatively (i.e. number of enrolled individuals, organisations, etc), while the networking event qualitatively (i.e. interviews, feedback, ethnography).

The key next step is to tie the intervention with the outcomes/impacts through an advanced cost benefit analysis. In the example given, this can be done by analysing the investment made with respect to the growth and revenue of the companies most interconnected within the newly established network, comparing to the more peripheral ones, or ones outside the network.

The last part is the crucial correlation, which provides tangible benchmarking for the overall success of a programme (within the cost benefit analysis). This is done by comparing the noticed trends in key parameters (in our case job creation, revenue growth, etc.) with corresponding regional, sectoral, national or global trends. The key objective is to trace any significant difference which can then be (in part! – see below) attributed to the intervention.

Crucial information, however, comes from the collected qualitative data which maps the action to its value for the participants, i.e. what was the contribution of a specific intervention to the overall change. For instance, in the example above we investigate the effect/importance of the networking on business success. This data can only be obtained by interviewing the participants in networking events, and running surveys and focus groups with representatives of the companies/individuals on the database. The key questions to ask will be: What made the difference?; How?; and How significant was it? We can then comment on the part the intervention played in the difference found between the participants performance and correlated trends.

Overall, this approach enables the evaluator to marry the desirable clarity of cost benefit analysis, where standards of success/failure can be contested, with a more balanced set of criteria and tangible links. The key features are quantified data (engagement figures, costs, returns, growth, etc) about the intervention, which is qualitatively (interviews, focus groups, etc.) examined as a contribution towards the difference in participants’ performance with respect to correlated background trends (sector growth, national job creation, GDP, etc.) – revealing the impact of the programme.

As said, this new, Quantified Correlated Impacts (QCI), framework is currently under development and I am sincerely opening its tenets to comments and suggestions. (And, please, do have a look at the other posts in the series, too: ER1, ER2, ER3.)

Many thanks in advance!