Working with Challenges

As discussed in What is interdisciplinarity? there are various approaches available that allow us to work between disciplines in different ways. One model that has been very popular, in a variety of educational contexts, is challenge-led learning.

Richard L. Wallace and Susan G. Clark argue that ‘[i]nterdisciplinarity is inherently “problem-oriented” – that is, its theory and methods are designed to address the complexity of social and environmental problems’ (2017, 222). Such problems, including ‘climate change, poverty and conflict’ are sometimes called ‘wicked problems’, which are ‘messy and cannot be fully defined’ (McCune n.d.). These challenges ‘have no single obvious solution, require imaginative interdisciplinary problem solving, and bring together multiple stakeholders with diverse perspectives’. It is clear to see how interdisciplinary approaches can be of value in this context.

Challenge-led learning is an approach to interdisciplinarity that often involves collaboration between academia and external stakeholders, including partnerships with industry and international organisations (Klein, 2017). This wider movement towards problem-based approaches has strongly influenced the development of interdisciplinary research and education in the modern university.

However, it is important to remember that such dominant models are not the only way of practising interdisciplinarity. While a range of positive and progressive learning outcomes can arise from ‘challenge-led’ and ‘problem-oriented’ approaches, there is a risk of a functional and solution-focussed experience, which could limit creativity and exploration. How can challenge-led learning maintain these qualities? Some of the activities suggested in this section have this aim.

With this caveat in mind, TILT offers some starting points for working with global challenges. The four subsections below each represent a different category of challenge questions: inequality and wealth, sustainability and biodiversity, peace and conflict, and global health. These categories are not discrete or exhaustive. Rather, they suggest some potential areas of enquiry, all of which interconnect and overlap in productive and generative ways.

Each category includes an overview, a suggested challenge question (which aspires to positive change), and a series of sub-questions that interconnect with the other categories. Suggested activities, resources and examples are included to inform the development of challenge-led learning in the interdisciplinary classroom.

All of these topics can be overwhelming and difficult to spend time with. It is important to consider how learners and teachers might be affected by the questions and activities. Our section on Ethical practice considers some of the positive and inclusive practices that could enhance an interdisciplinary approach to education, without causing unnecessary distress or missing the opportunity for careful and sensitive collaboration.

Inequality and wealth

According to the United Nations (n.d. a), ‘Inequality threatens long-term social and economic development, harms poverty reduction and destroys people’s sense of fulfillment and self-worth’. Inequality is a particularly powerful topic for interdisciplinary learning and teaching, because it requires a recognition of interconnectedness:

In today’s world, we are all interconnected. Problems and challenges like poverty, climate change, migration or economic crises are never just confined to one country or region. Even the richest countries still have communities living in abject poverty. The oldest democracies still wrestle with racism, homophobia and transphobia, and religious intolerance. Global inequality affects us all, no matter who we are or where we are from. (United Nations, n.d. a)

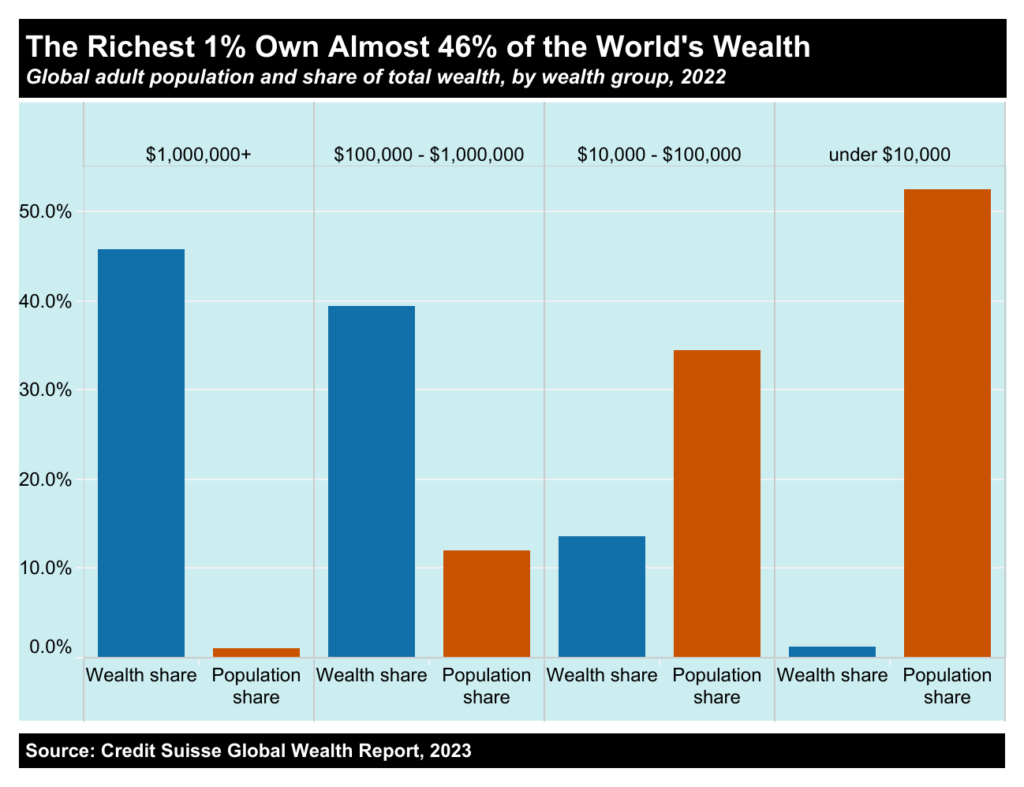

Economic inequality is just one part of a much wider, more complicated story. Nevertheless, it offers a productive starting point for work in this area. It brings us very quicky into the world of data, and visualisations such as this one offer striking representations of global wealth distribution.

Image available at https://inequality.org/facts/global-inequality/. CC BY 3.0.

While it may be useful to start with a question related to wealth distribution, there are a range of social, cultural and ecological power dynamics that can be brought into the discussion. The sample questions here aim to bring a range of global challenges into a dialogue, suggesting that interconnectedness is at the heart of inequalities research.

Challenge question:

How can we reduce the gap between rich and poor?

Subquestions:

How is wealth distributed?

Who has access to greenspaces?

What is the relationship between crime and inequality?

How does inequality affect access to healthcare?

Suggested activities:

- Games – an effective way of exploring inequality in the classroom can be through card or board games, role play and simulations. Active Learning in Political Science has a collection of links to lesson plans that use games (the Economics section and the game on Global Inequality are relevant to this challenge topic on Inequality and Wealth). Games such as the 2030 SDGs Game can be used to demonstrate what is at stake if our primary goal is acquisition of wealth. Or get creative with coins, counters, cards or sweets.

- Maps – a powerful way of visualising wealth inequality, maps such as those published by the Office for National Statistics can prompt discussion and inspire further research. Explore economic inequality in the UK and ask, ‘What are the regional differences in income and productivity?’. This example also provides a dataset, which can be further explored through Methods for interdisciplinary research. Create new maps from data, such as house prices, Airbnb properties, or proximity to greenspace, and consider what this tells you about a city’s inequality.

- Intersectionality – the problem with focussing on wealth and economic inequality is that it can obscure other forms of social and cultural inequality, all of which interconnect in various ways. Intersectionality is ‘way to think about how these distinctions [of race, gender, social class, sexuality, etc.] are socially constructed such that they depend on one another for meaning’ (Cole 2016, ix). This video introduces different models of intersectionality, which can be used to introduce Ashlee Christoffersen’s framework for competing concepts of intersectionality (2021, 579).The framework can be used as a teaching resource by asking learners to work in groups, researching examples of policy and practice that align with Christoffersen’s five concepts.

- Ethical practice – the TILT section on Ethical practice offers a range of concepts, methods and resources that can be useful for any learning and teaching activities that focus on inequalities.

Sustainability and biodiversity

Sustainability incorporates a wide range of interconnected factors. As such, it is a popular topic for interdisciplinary education. There are many definitions of sustainability, and the term is used in various contexts, from economics to culture. Environmental sustainability is a key concern for many, and a useful starting point is provided by the campaigning charity, Greenpeace (n.d.):

Sustainability is a way of using resources that could continue forever. A sustain-able activity is able to be sustained without running out of resources or causing harm.

If something is unsustainable, it means it’s using up resources faster than they’re being replaced. Eventually the resources will run out and the activity won’t be able to carry on.

As the environmentalist George Monbiot (2012) points out, there is an all-to-easy slippage from sustainability, through ‘sustainable development’ to the flatly contradictory notion of ‘sustained growth’. The term ‘green growth’ also offers a provocative topic for debate.

The wide-reaching purview of sustainable development is highlighted by the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Again, the interconnectedness of global challenges is emphasised, as ‘ending poverty and other deprivations must go hand-in-hand with strategies that improve health and education, reduce inequality, and spur economic growth – all while tackling climate change and working to preserve our oceans and forests’ (United Nations n.d. b).

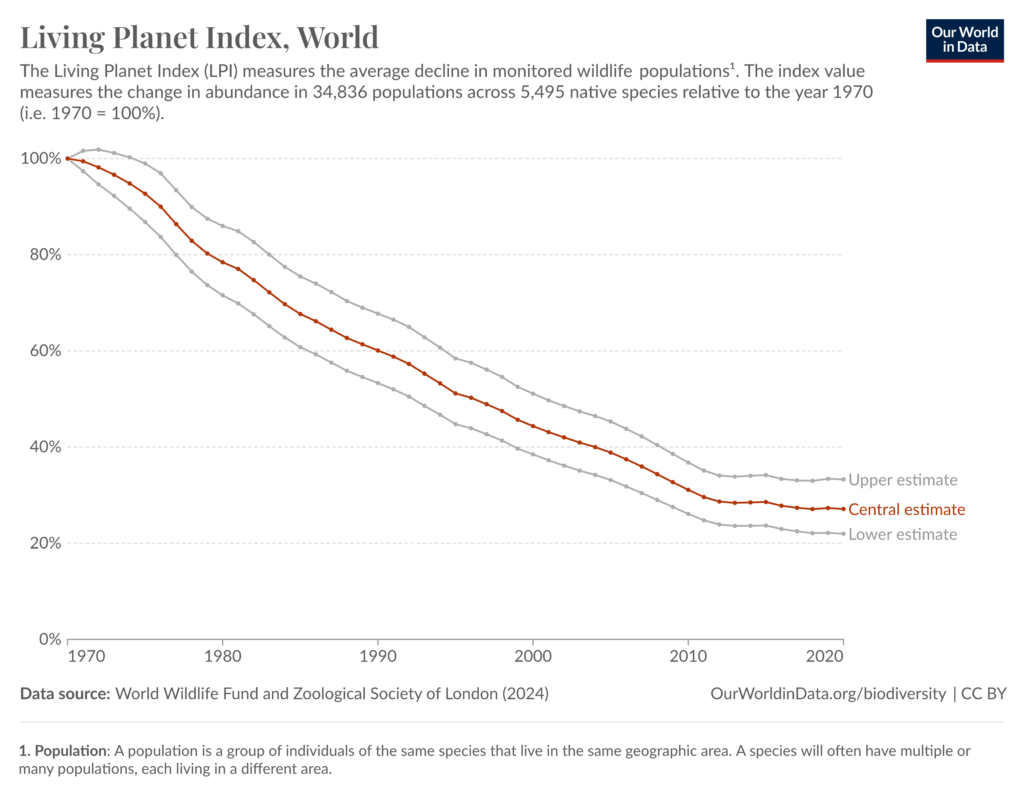

All of the 17 SDGs could offer productive topics for interdisciplinary education. For example, the goals for ‘life below water’ and ‘life on land’ raise some important questions about biodiversity that can be used effectively to structure interdisciplinary learning and teaching. Some exciting, difficult, and cautiously hopeful projects can emerge from an interdisciplinary response to the biodiversity crisis, which is strikingly illustrated by the Living Planet Index:

The global LPI as presented in the Living Planet Report 2024 (WWF) shows that a subset of 34,836 populations of 5,495 species has declined by an average 73% in abundance between 1970 and 2020 (WWF and ZSL 2024).

There is a lot to ask about this data. Why 1970? Which regions are omitted or underrepresented? Which species are left out of the picture? Nevertheless, the striking decline in biodiversity over half a century of data collection, is a provocative starting place.

These sample questions aim to highlight the ways in which biodiversity is impacted by, and makes an impact on, other global challenges such as inequality, conflict and global health.

Challenge question:

How can we enhance biodiversity?

Subquestions:

How and in what ways has biodiversity been impacted by globalisation?

Who owns the land and controls its use?

What is the impact of conflict on ecosystems?

How is wellbeing affected by biodiversity?

Suggested activities:

- Biodiversity sampling – moving outside the classroom into local greenspaces is a valuable way of connecting learners to the natural world. Sampling can be conducted using string and tent pegs to demark sampling areas. A 12m long string can be folded into 4 and arranged in a square using 4 people in a team at each corner. Groups can spend 20 minutes at a number of separate locations and use a spreadsheet to record data sightings. They can use the recommended apps (Woodland Trust app, Merlin, Picture Insect and Google Lens) to help with species identification, which they can download and familiarise themselves with prior to the workshop. Discussion can then focus on overall impressions of biodiversity and questions of land usage at the site. (For an interesting interdisciplinary discussion of using quadrants, see Sanders and Davies (2023). This chapter connects to the discussion of Karen Barad in the TILT sections on What is interdisciplinarity? and Ethical practice, by bringing Barad’s theory into the use of quadrants in outdoor learning and ecology education.)

- Biodiversity footprints – while the calculation of carbon footprints is widely practised across multiple sectors, the concept of biodiversity footprints is developing. An individual or group activity could identify a particular source of biodiversity decline (an arts project, a class or an individual’s commute, for example) and calculate biodiversity impact. Lasse Miettinen (2024) provides a valuable step-by-step guide which could be adapted for a learning project. This involves: collecting data on the subject to be measured; deriving pressures on nature; deriving impact on biodiversity; and combining these impacts to calculate the biodiversity footprint.

- Biodiversity resources – The World Wide Fund for Nature has a wide range of biodiversity resources for educators, primarily aimed at grades 6-8, but adaptable across learning levels. This includes workshop plans for role-playing activities, creating news reports, and designing products. The disciplinary alignment is indicated (science or art, for example), but there is a productive slippage between approaches in many of these tasks.

- Cards – WWF also provides a collection of wildlife species cards, which provide learners with a fun way to learn about animals, their importance in their ecosystems, characteristics, lifestyles, and the threats they face. Use these cards as a stand-alone resource or to supplement other lessons.

Peace and Conflict

Conflict can be explored at different scales: from large-scale global warfare to local political events, to individual struggles that we experience every day. These forms of conflict are not distinct or discrete categories. Rather, there are myriad complex interconnections between our everyday lives, sense of identity, membership of communities and international contexts. Interdisciplinarity can be a powerful model for learning across and between these different forms of conflict.

There is a huge amount of data on global conflict, some of which can provide an effective starting point to address this topic. The Center for Preventive Action (USA) manages a useful Global Conflict Tracker, which provides ‘an interactive guide to ongoing conflicts around the world of concern to the United States’. This includes contextual information and a range of resources on almost thirty global conflicts.

Yuval Noah Harari and Itzik Yahav offer some valuable resources for learners and educators through their social impact company, Sapienship. These questions can orientate a learning community addressing a challenging topic:

-

- Is your country at war? If so, do you see a way out?

- What are some of the reasons countries go to war?

- Is there such a thing as a just war? What distinguishes a just war from an unjust one?

- People often believe that some wars will last forever. Why do you think that is?

- Can you think of something that lasts forever? If yes, what is it? If not, why do you think nothing lasts forever

- Yuval Noah Harari once said, ’The single greatest constant of history is that everything changes.’ What do you think he meant by that? Do you agree?

- Are you afraid of change? What kind of change do you fear the most, and how do you cope with it?

As with many of the topics introduced in this section, work on conflict can be very difficult and upsetting, particularly for those who have had direct experience of war. The Red Cross have issued a valuable guide, How to talk to children and young people about conflict. While this resource is age-specific, read alongside some of the ideas and activities in the TILT Ethical Practice section, it is a useful prompt towards careful and ethical approaches to learning and teaching about conflict.

Challenge question:

How can shared values reduce conflict?

Subquestions:

How has conflict changed in the 21st century?

What forms of inequality emerge in fragile or conflict-affected economies?

Why is peace necessary for sustainable development?

How does conflict affect mental health?

Suggested activities:

- Preparing to discuss conflict – Share the conflict questions from Sapienship (above) with learners before a class. Ask them to reflect on them individually in preparation for a group discussion. During the class, ask whether anyone would like to share their thoughts in response to any of the questions. This ensures readiness and willingness to talk about potentially challenging topics, which may include lived experience of war.

- Quiz – introduce international conflict with this interactive quiz by Gapminder, which usefully challenges common misconceptions about global conflict.

- Case studies – Using the global conflict tracker, ask small groups of learners to research a specific conflict in order to present an overview of key issues to the rest of the class. Encourage a critical consideration of how and why the data is presented in the way that it is. Are there any biases apparent in this resource?

- Conflict resolution activities – There are many conflict resolution games available, each of which offers different ways of exploring conflict that may be appropriate for the interdisciplinary classroom. One good example is the Conflict Resolution Network’s Conflict Resolving Game, which ‘asks participants to build on, and add value to, each other’s points’. The game ‘rewards creative response to another’s statement, rather than opposing it’ and as such can foster interdisciplinary dialogue and integration. It is also important to reflect on what the final goal should be in conflict resolution. The TILT section on Ethical Practice refers to Wolfgang Deitrich’s (2014) discussion of ‘elicitive transformation resolution’, a method of conflict resolution which challenges notions of a finalised stage called ‘peace’. Could this approach be incorporated into activities, which sometimes obscure the cultural and ideological differences that might be important to identify and avow?

Global health

Interdisciplinarity has become an important approach to addressing the challenge of global health. For example, The Usher Institute at the University of Edinburgh brings together researchers in epidemiology, statistics and modelling, informatics, computer science, clinical science, sociology, social policy, governance, ethics, politics, medical law psychology, economics, geography, health promotion and medicine. These researchers are working together to improve the health and wellbeing of patients, communities and populations locally and globally.

There is great potential in addressing global health as a challenge for interdisciplinary learning and teaching. A good place to start is the World Health Organisations series of Fact Sheets, which cover a wide range of topics, from Climate change to Food safety. As with all the topics in this section, it soon becomes clear that global challenges are interconnected. Collaboration across knowledge areas is essential.

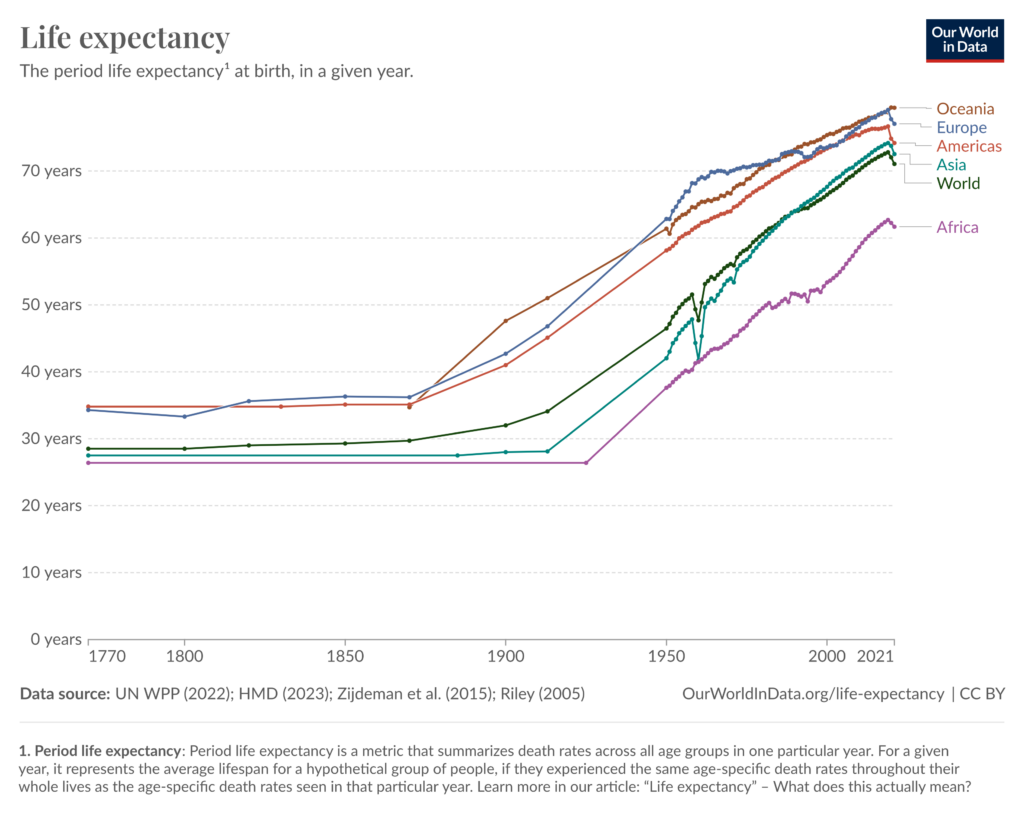

Exploring global health data soon reveals massive inequality. This chart, available on the Our World in Data page for Global Health, summarises the available data on life expectancy over the last few centuries:

For an interactive version of this chart, see https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/life-expectancy

As always, any encounter with data opens up more questions than it answers. Life expectancy is a difficult thing to measure, because it is only possible to consider a historic cohort (those who have already died) or take a hypothetical approach to a period, even though mortality rates are changing all the time (Ortiz-Ospina 2017). These data also raise questions about why there is a difference in global regions, what the different causes of mortality rates might be, and what factors might impact results (for example, inequality, sustainability and conflict). The following questions suggest ways of bringing these global challenges into a dialogue:

Challenge question:

How can we improve global health?

Subquestions:

What is an interdisciplinary approach to health care?

How is healthy life expectancy distributed?

What is the connection between biodiversity and global health?

What are the effects of conflict on regional health?

Suggested activities:

- Public health resources – Ablconnect at Harvard University includes public health learning activities, including: Humanitarian Funding Simulation – learners participate in a simulation of groups proposing grants to a funding agency to deal with a humanitarian crisis. Adopt a Country – learners ‘adopt’ a country to follow and research for the semester.

- Debate – CFR Education from the Council on Foreign Relations (USA) provides a list of questions on global health, for example: ‘How well prepared for a major disease outbreak is the world?’. These can be used to prompt debate between groups, or offer starting points for independent research tasks.

- Poetry – the Scottish Poetry Library hosts the Poetry for Wellbeing toolkit (created by Autumn Roesch-Marsh, Ariane Critchley and Samuel Tongue), which offers a practical guide to running your own poetry group, with an emphasis on how reading and writing poetry can support positive mental health, and is available for anyone to use and download. The programme is created primarily for social workers, but the ideas and activities are valuable in lots of different contexts.

A full list of references for the TILT site is available here.

Comments are closed

Comments to this thread have been closed by the post author or by an administrator.