What is Interdisciplinarity?

Why interdisciplinarity?

Interdisciplinary learning and teaching have become increasingly popular across different levels of education. They suggest new ways of working and offer a number of benefits, including:

- Deep engagement with complex challenges

- Ability to solve problems and develop critical thinking

- Increased relevance and responsiveness to the world

- Learning with a wide range of collaborators

In many educational contexts, including Western universities, training, study and assessment are traditionally organised around distinct disciplines. For a long time, interdisciplinary approaches have been developed to challenge this dominant model and to provide alternative spaces for working together across epistemic boundaries.

Today, new interdisciplinary programmes are being created, curricula are evolving to become more flexible and open to integration, and mixed research methods are being taught and practised.

By its very nature, interdisciplinarity means different things to different people, and is practised in various contexts with unique methods and applications. This is one of its main strengths. Perhaps the most compelling reason to develop interdisciplinary approaches is the agency that is afforded to chart new paths and find new ways of learning and teaching.

In this video, learners and educators from the University of Edinburgh’s Interdisciplinary Futures degree introduce their approach to challenge-based learning and reflect on the value of interdisciplinary education.

Definitions and versions

The term interdisciplinary is contested and difficult to define, but as a model for learning and teaching, it has a lot of potential to bring us together with people we would not normally work with, and to challenge us to think in creative ways with new ideas and methods.

The prefix, inter- is a good place to start. Inter means between. When we work between disciplines, we create a space for connection, exchange and collaboration. Many definitions of interdisciplinarity emphasise this relational quality. For example, Katrine Lindvig and her co-authors adopt a broad definition referring to ‘any dialogue or interaction between two or more disciplines’ (2019, p. 348). Often, this dialogue or interaction is assumed to take place within the academy. Robert Frodeman refers to the ‘intra-academic integration of different types of disciplinary knowledge’ (2017, p. 4). In these examples, the integrity of disciplinary knowledge is maintained. However, Joe Moran explores the possibility of moving beyond disciplinarity:

[interdisciplinary] can suggest forging connections across the different disciplines; but it can also mean establishing a kind of undisciplined space in the interstices between disciplines, or even attempting to transcend disciplinary boundaries altogether. (Moran 2010, p. 14)

The idea of an undisciplined space implies a rejection of, or at least a willingness to test the ‘rules’ of educational systems and processes. This might take us outside the academy.

We might follow the Indigenous and non-Indigenous research collective of Bawaka Country to challenge ‘the notion of universities as the centre of knowledge production’ (2019, 694). Interdisciplinarity has the potential to move us out of our institutions to engage with, learn from, and become with the world around us. If an understanding of disciplines can be expanded beyond Western conceptualisations of academic knowledge, then the idea of moving between disciplines takes place in a hugely expanded field.

These definitions and provocations represent different ways of thinking about and practising interdisciplinarity. If we understand interdisciplinarity broadly and accept that it might be practised in different ways in different contexts, then we avoid the prescriptiveness that may be inimical to the relational potential of this approach. Whether interdisciplinarity is understood as the careful integration of disciplinary perspectives, or a radical openness to our environments, it is a way of working that takes us beyond traditional approaches to education, into exciting new fields and practices. After all, as Moran suggests:

[…] the value of the term, ‘interdisciplinary’, lies in its flexibility and indeterminacy, and […] there are potentially as many forms of interdisciplinarity as there are disciplines. In a sense, to suggest otherwise would be to ‘discipline’ it, to confine it within a set of theoretical and methodological orthodoxies. (Moran, 2010, p.14)

Flexibility and indeterminacy are very much at the heart of this toolkit. This allows interdisciplinary learners and educators to remain open to new ways of working: ‘receptive to chance and perceptive of change’ (Overend and Lorimer 2018, p. 529).

Nevertheless, as the scholarship of interdisciplinary learning and teaching expands, there are many valuable conceptualisations of interdisciplinarity to draw on. The following sections offer some examples and explore some of the distinctions and models that emerge from the literature. This provides a context for the sections of the Toolkit for Interdisciplinary Learning and Teaching (TILT), which support and promote a pluralistic engagement with interdisciplinarity. This is a selection of examples rather than an exhaustive typology.

Podcast

Interdisciplinary Futures student Emily Shaw asks What is Interdisciplinarity? and interviews interdisciplinary educators, David Overend and Gill Robinson:

Further information available on the University of Edinburgh’s Teaching Matters blog.

Multi- / Inter- / Trans-

Interdisciplinarity is generally considered to be something quite different to multi-disciplinarity (meaning many disciplines), which brings together different perspectives and approaches, but does not necessarily integrate them. For example, Rebecca Turner and her colleagues at the University of Plymouth, explain the distinction:

[I]nterdisciplinarity involves the merging or integration of disciplinary knowledge to offer novel perspectives, unlike multi-disciplinary approaches in which each discipline contributes from its epistemological origin but remains fundamentally unchanged by its encounter with alternative views. (Turner et al. 2024, p. 1093).

This suggests that interdisciplinarity has the power to change established disciplines by bringing them into new configurations and relationships with each other.

A good example of this is the way in which geographers have been drawn towards artistic methods in such a way that a whole new sub-discipline of creative geography has emerged. Artists can be geographers and geographers can be artists. And both now understand and apply each other’s methods (Hawkins 2021).

Another common term is trans-disciplinary. This term is often used to describe an approach that not only moves between different academic disciplines, but may even escape the boundaries of the academy all together to engage with other types of knowledge and practice out there – in the ‘real world’ (Bammer 2013).

While universities are always inevitably part of the ‘real world’, the emphasis here is on collaborations that include diverse academic disciplines interfacing with external partners.

As Tanya Augsburg explains, one of the key conceptualisations of transdisciplinarity is ‘as problem-focused with an emphasis on joint problem solving at the science, technology, and society interface that goes beyond the confines of academia’ (2014, p. 235). A similar definition is offered by Andrew Barry and his co-authors:

[Transdisciplinarity] is taken to involve a transgression against or transcendence of disciplinary norms, whether in the pursuit of a fusion of disciplines, an approach oriented to complexity or real-world problem-solving, or one aimed at overcoming the distance between specialized and lay knowledges or between research and policy […] (Barry et al. 2008, p. 27).

Insofar as it is useful to distinguish between ‘intra-academic integration’ (Frodeman), going ‘beyond the confines of academia’ (Augsburg) and ‘real-world’ problems (Bammer; Barry et al.), the inter and trans prefixes help to define different types of activity and collaboration that might comprise a project that takes a novel approach to learning and teaching.

However, if a more pluralistic understanding of interdisciplinarity is accepted, then the boundaries between these terms may usefully be understood as more fluid and adaptable. It is important not to get too hung up on semantics and TILT follows Barry et al. in using ‘interdisciplinary’ to refer to a broad spectrum of activities, from the exploratory collaboration of multi-disciplinarity to the paradigm shifting potentials of trans-disciplinarity.

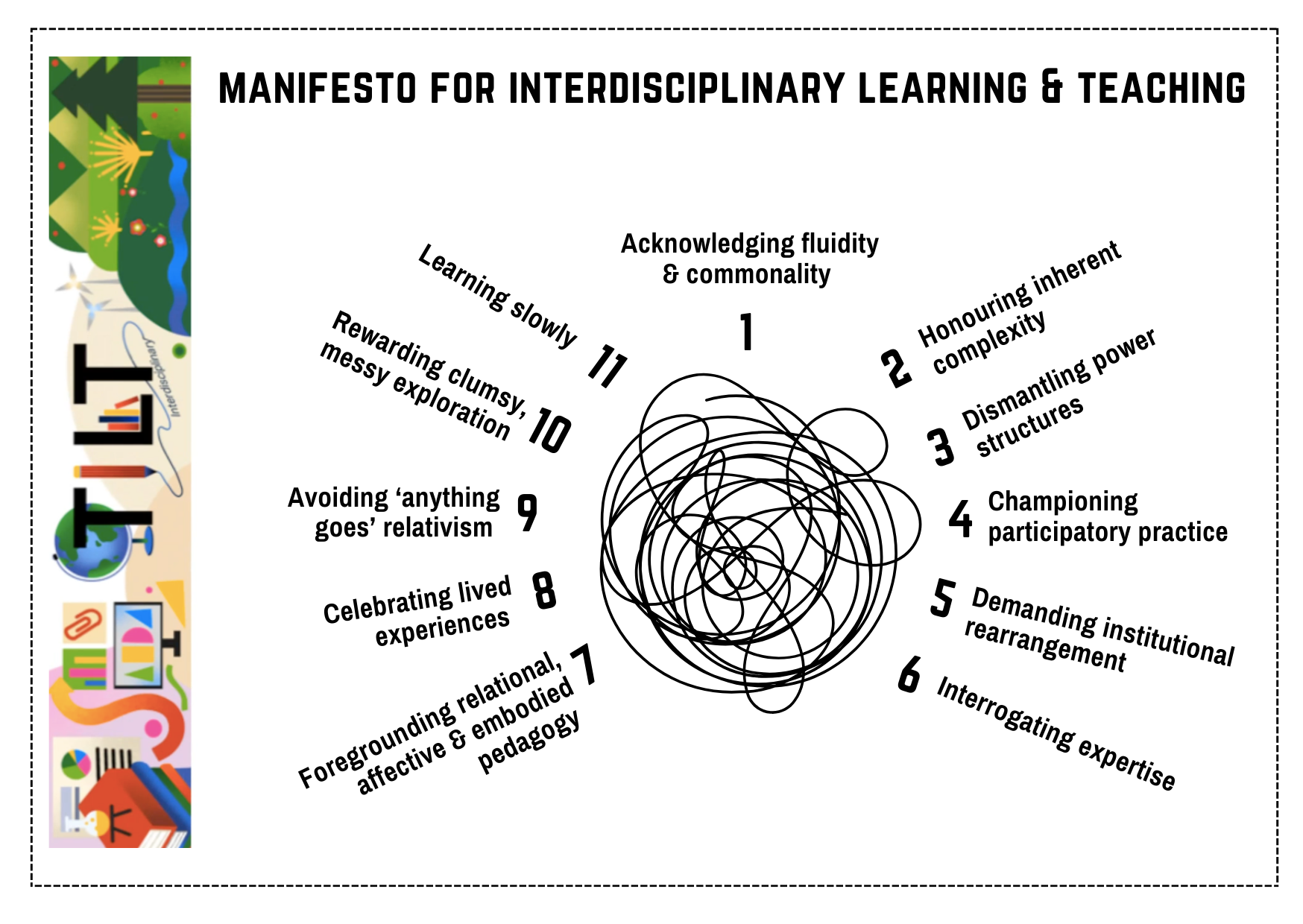

Activity: Manifesto making

Due to the vast range of competing definitions of interdisciplinarity, it can be useful for a new group to find some common ground. An effective activity is to write a manifesto together.

Manifestos often initially appear confident and totalising, suggesting an authority not yet possessed; they propose an imagined and desired future, but they simultaneously deploy irony and ambiguity to balance, or even counter their own prescriptiveness. This means that manifestos should open up debate, rather than closing it down.

Here is an example of a manifesto for interdisciplinary learning and teaching, compiled by Jenny Scoles, Clare Cullen and Maddie Winter at the University of Edinburgh, with a film by Simon Dures:

This manifesto can be used as part of a teaching activity by asking learners to decide which statements they agree with, which they are opposed to, and which they would want to rewrite. This will help groups decide what is important to them as they embark on an interdisciplinary learning journey. The document could be returned to at the end of a course or project, to see if the statements need to change.

Modes and models

Of course, if we define everything that we do in relation to disciplinarity (whether multi-, inter- or trans-), then the idea of the discipline still carries a lot of weight. There is, perhaps, a tension between ‘inter’ and ‘discipline’ in some of these formulations, as alternative spaces are created that paradoxically rely on the disciplinary infrastructure that they exist within.

Agonistic-antagonistic model: An antagonistic (or more positively, agonistic) relationship occasionally emerges between the integrity of the disciplines and the practice of interdisciplinarity. Barry and his co-authors (2008) see such tensions as a strength of interdisciplinarity, drawing on radical democratic theory to emphasise the inherent value of conflicts, tensions and agonism, ‘to challenge and transform existing ways of thinking about the nature of art and science, as well as the relations between artists and scientists and their objects and publics’ (p. 25). The disruptive potential of interdisciplinarity can be a powerful way of challenging and changing established ways of working.

For Barry and his co-authors, ‘interdisciplinarity should not necessarily be understood additively as the sum of two or more disciplinary components or as achieved through a synthesis of different approaches’ (p. 28). The agonistic-antagonistic model is in contradistinction to more utilitarian approaches, which emphasise the importance of integration. In some cases, a refusal of integration defines an interdisciplinary approach. Rather than using yet another prefix and suggesting an anti-disciplinarity, a conflicted ‘relation to existing forms of disciplinary knowledge and practice’ is identified, in which ‘interdisciplinarity springs from a self-conscious dialogue with, criticism of or opposition to the intellectual, ethical or political limits of established disciplines’ (p. 29). In this sense, interdisciplinarity holds the potential for disruption and political intervention.

When synthesis and integration are emphasised, there is a risk of closing down possibilities, or even unquestioningly shoring up disciplinary dominance (Barry et al. 2008). This is sometimes seen in the various ways in which disciplines have been interconnected in response to large-scale global challenges, such as climate change.

Challenge-led interdisciplinary learning: The challenge-led model of interdisciplinarity is widely practised in different educational contexts. When disciplinary tradition and established ways of doing things are removed from, or repositioned within, a learning experience, complex challenges can provide a valuable point of focus. The rationale for interdisciplinarity at the modern university often refers to problems that cannot be adequately addressed within a single discipline. The opening of Keisuke Okamura’s article on the evidence for research impact and dynamism of interdisciplinarity is one of many examples of this argument:

Many of the world’s contemporary challenges are inherently complex and cannot be addressed or resolved by any single discipline, requiring a multifaceted and integrated approach across disciplines. (Okamura 2019, p. 2)

The challenge-led approach has huge potential for societal and planetary benefits. However, it is not the only way of practising interdisciplinarity and all too often, challenge-led and interdisciplinary learning are perceived as synonymous, particularly in the modern university.

Interdisciplinary environments: One alternative approach is to explore an interdisciplinary environment, such as the contemporary city (Overend et al. 2024, Cullen et al. 2024). In the University of Edinburgh’s Creating Edinburgh: The interdisciplinary city (available as an Open Educational Resource), students are invited to explore the city as an interdisciplinary learning space. The course is organised around a series of topics, which include Decolonising Edinburgh, Sustainable Edinburgh and Designing Edinburgh. Learners follow a set route each week, returning to the classroom to share experiences and documents from their urban fieldwork, building an interdisciplinary understanding of the perspectives, practices and people who comprise the city.

Diffracting interdisciplinarity: Another way of thinking about the potential of interdisciplinary learning and teaching is through Karen Barad’s (2007) concept of diffraction. Arising from an interdisciplinary dialogue between physics and feminist theory, Barad’s complex ideas have been taken up in education studies as a way to move away from the interpretive and analytical approaches, which can reinforce and reproduce existing hierarchies (Bozalek and Zembylas 2018, Murris 2022, Spector 2015). By turning ideas and experiences over and over (re-turning), diffractive methods produce difference and resist closure.

Here are two lesson plans created for TILT by David Jay (Anglia Ruskin University), to introduce a diffractive methodology to the interdisciplinary classroom: PDFs are available for Tracing Entanglements and Diffractive Questioning, both of which are intended to be used flexibly as practical activities in different learning contexts. Tracing Entanglements uses objects to foster diffractive thinking; and Diffractive Questioning promotes the values of open and generative questions.

The diffractive model might be understood as post-disciplinary. This is because the synthesis that is required to organise knowledge within the confines of a discipline is perpetually deferred by Barad’s practice of continually re-turning ideas, concepts and methods. Or perhaps, more helpfully, it can be used as part of a rich assemblage of learning and teaching practices that emerge around the idea of interdisciplinarity.

It will be clear by now that there are many different, occasionally conflicting, ways of understanding interdisciplinarity. Embracing this plurality, the Toolkit for Interdisciplinary Learning and Teaching has been created to support a range of diverse modes and models. TILT therefore offers a collection of different methods, focusses, activities, and principles. It is hoped that this will complement and enhance the work of learners and educators in this expanded field, inspiring new approaches and ways of working.

A full list of references for the TILT site is available here.

Comments are closed

Comments to this thread have been closed by the post author or by an administrator.