Collaboration

Collaboration is an important, and often essential, part of interdisciplinary learning and teaching; it can take various forms. However, teamwork is not always well supported in learning programmes and collaboration is sometimes just expected to happen. This section highlights the benefits of teamwork for learners. It provides some resources and tasks to support collaborative learning and teaching across four categories: Working in groups, Leadership, Collaboration across disciplines, and Working with external partners.

There are a number of specific challenges posed by interdisciplinary collaboration, as discussed in this video by Utrecht University, which considers issues around complexity, diversity, interdependence and creativity:

Working in groups

Group or teamwork can be demanding and difficult, yet it is vital participants learn to work well with each other – understanding how to compromise and, where desirable, to find consensus. Diverse teams made up of learners from various disciplinary backgrounds with different life experiences informed by their gender, race, class, ability, etc. encourage learners to develop intercultural and interpersonal skills.

Fostering positive working relationships built on trust is a vital first step towards successful teamwork (Barkley, Cross, & Major 2014). Participants should be encouraged to spend time getting to know each other at the beginning of any project. This process can be better facilitated through something like this Team Skills Audit developed by the Centre for Professional Skills Team at Rotman Commerce University of Toronto. This video tutorial explains how to use the document:

A Teamwork Contract, setting out ground rules as well as role and task assignments can help to pre-empt or mitigate conflict as participants work together. By making expectations explicit, individual members can hold each other accountable, making them more autonomous as they progress.

Interactional Discourse Lab is a tool that can help both educators and students to capture and make sense of their group’s dynamic and effectiveness. It can be used to offer insights for students about their engagement- prompting reflection and growth; it can also offer alternative options for assessment of teamwork.

Leadership

Leadership is already a hotly contested concept amongst educators and researchers. In practice, however, leadership is discursively constructed by higher education institutions as a set of skills that can be acquired; this is largely in response to labour market demands. This characterisation most resembles the process (Burns, 1978) and systems-oriented (Senge et al., 2015) perspectives in the literature—whereby leadership is characterised as something that can be taught. However, such an approach locates leadership within the leader; the primary unit of analysis and for improvement is the person—reinscribing leader-centricity.

Various frameworks to account for skill acquirement as related to leadership have been developed. Professionalised disciplines, like engineering or business management, have taken a pragmatic approach. For example, educators have set out six Elements of Engineering Leadership: character development, business knowledge, interpersonal skills, intrapersonal skills, management skills, and the study of leadership (Daly & Baruah, 2021), and MBA programs list leadership amongst their top learning outcomes (Okudan & Rzasa, 2006). In contrast, theatre studies grapple with leadership ‘as an art’ (Biehl-Missal, 2010), as something to be understood with and through performance and aesthetic (Katz-Buonincontro, 2011). While sociologists seek to uncover the origins of leadership (Garfield, Syme, & Hagen, 2020), approaching it as highly politicised (Viviani, 2017), and drawing on theories of power put forth by Bourdieu and Foucault to inform the teaching of leadership (Bogotch et al., 2008; Gunter, 2010). In anthropology, teaching leadership is underpinned by ‘methods that take sociocultural dynamics seriously’ (Johnson, 2007, p. 213).

Data collected from the Edinburgh Futures Institute’s undergraduate course, Students as Change Agents, provided evidence for the ways in which traditional and disciplined concepts of leadership are troubled in the interdisciplinary classroom (Winter & Overend, 2024). There is often no obvious content expert in the interdisciplinary classroom and, especially in challenge-based interdisciplinary contexts, the instructor or coach plays the role of a facilitator rather than a traditional lecturer. The analysis produces a novel characterisation of interdisciplinary leadership as a ‘temporal sensibility that can be taken up, put down, passed around and shared by any and all members’ of a team (ibid., p. 85).

As mentioned in other sections of TILT (see Ethical Practice), interdisciplinary education can be an emotional and challenging process. Part of the uncertainty of the learning process is that many things learners take for granted in disciplined classrooms no longer apply—including traditional leadership and teamwork roles. Here is a Challenging Assumptions about Leadership workshop plan aimed at ushering learners through the assumptions they hold about leadership.

Collaboration across disciplines

Despite the common desire and anticipated value of collaboration across disciplines, working together rarely unfolds in the ways we expect. In his work on radical collegiality, Michael Fielding, addresses both practical and theoretical notions of collaboration and collegiality in order to purposefully differentiate between them (1999). He argues that ‘collaboration is an overidingly instrumental form of activity’ bred of individualistic teaching cultures, while collegiality is ‘communal in form and in substance’ as ‘its intentions and practices make no sense outside a way of life and a tradition which is expressive of collective aspiration’ (ibid., pg. 17). The three primary strategies for fostering an inclusive collegiality are:

(1) Energising equality: the power of peer learning,

(2) Students as teachers: teachers as learners,

(3) Taking democracy seriously: reconstructing education as a democratic project.

It can be difficult to know where to start with a co-creative process. The Co-creation of Learning and Teaching Typology table (Bovill, 2019) is a useful tool for identifying, individually or collectively, how a co-creative project might progress.

Working with External Partners

Collaborating with external partners can be especially stimulating for interdisciplinary learning. In this section we outline the role external partners play on one of the undergraduate courses offered by Edinburgh Futures Institute and highlight some of the ways external partners can be engaged with.

Students as Change Agents and External Partners:

Students as Change Agents (SACHA) was originally offered at the University of Edinburgh as an extracurricular program in 2019, and in the years that followed engaged more than 30 external partners. A curricular version, offered by the Edinburgh Futures Institute since 2022, works with partners organisations who pose an interdisciplinary problem for learners to respond to. For instance, the partner for the pilot run, the Data for Children Collaborative, posed the question, ‘How might the mental health of children living in Scotland be improved?’. The next years question was, ‘How can we effectively communicate and engage with marginalised communities in order to empower climate action?’. Recent iterations of the course dealt with issues concerning the safeguarding of children and diversity in the construction sector. The student teams work towards presenting a set of recommendations to the partner along with a written report; they also receive feedback from the partner throughout the process.

Learners on SACHA often noted that working with an external partner was novel in the context of their university experience:

I was excited to get a more hands-on opportunity to use my knowledge and interact with real world partners rather than with theory just re-enforcing my own worldview and solutions onto the problems

The biggest opportunity was to get really deep into the challenge posed by the external partner. I liked that we were able to talk with them

Their exposure to ‘real world problems’ inspired learners to become more active, or pursue careers in relevant fields:

I have been completely inspired to get more involved in environmental activism and the positive response from the team to our ideas, and presentation has given me the confidence to aim for the career in politics which I have always wanted to do, but not had the confidence to properly pursue

External partners also recognise the value of their collaboration with the university and students:

Having such insightful and really well articulated ideas has really given us a lot of food for thought, and it will totally inform our work

I’ve been hugely impressed by both the calibre and enthusiasm of the students involved. We will mull over all that has been shared and consider if there are elements we can implement- now or in the future

Connecting with External Partners

The Public Services Innovation Lab at Edinburgh Futures Institute works to connect academics, practitioners, community members and other stakeholders to explore challenges they are facing together. Their work involves, appraising opportunities, sharing guidelines for collaboration to avoid siloing, and striving towards innovation and change. The Scottish Prevention Hub, for example, is a collaboration between EFI, Police Scotland, and Public Health Scotland. Staff from all three partners are co-located within the EFI, focusing their efforts on reducing inequalities.

In her work as Director of Public Services, Dr. Kristy Docherty (2024) has identified seven challenges to collaboration, as illustrated below.

©️ Docherty, K. 2024. CC BY 4.0 (Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International)

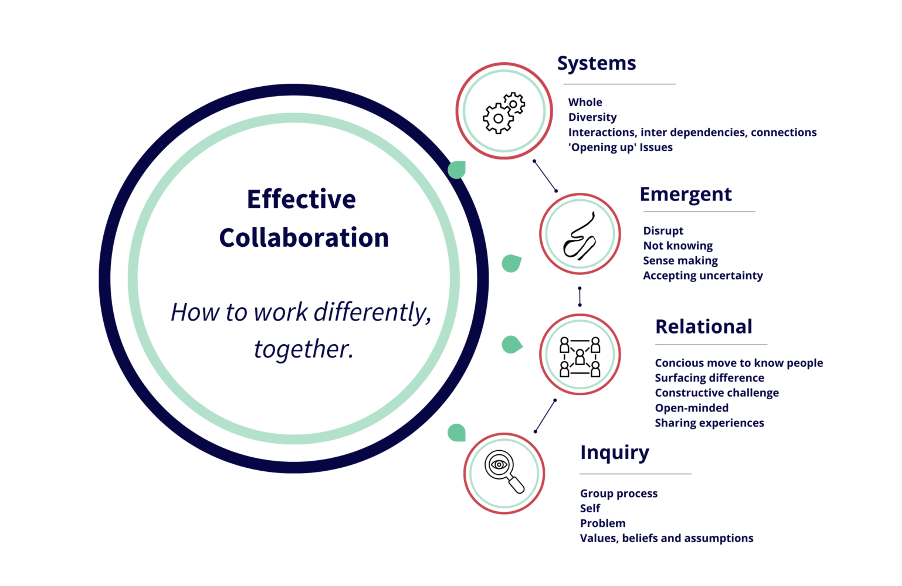

A four-principles approach, as shown below, provides the framework for collaboration at the Scottish Prevention Hub. Although the model was developed specifically to reduce health inequalities in Scotland with a focus on prevention, the approach can be applied to various contexts.

©️ Docherty, K. 2024. CC BY 4.0 (Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International)

When thinking about connecting with external partners it might be assumed that these relationships should be brokered at the institutional level, by representatives of the university. However, learners themselves come from rich communities of organisations and groups and are well placed to establish connections with partners as well.

Further resources on group work

• A Teaching Matters series on SACHA (2024) explores issues around mentoring, group dynamics, reflection and co-creation.

• In a Times Higher Education blog post, William J. Owen and Leah Chambers (2024) share their tips on how to turn individual wins into team achievements in group work. They argue for a systematic approach, which aligns with the principles of collaborative learning, and suggest a pre-project group development tasks and reflective activities to form a better group dynamic.

• Rotman Commerce, based at University of Toronto offers some useful Teamwork resources, such as Tips for Teamwork, and an example of a ‘Teamwork contract’.

• In a Teaching Matters blog post, Dr Rosie Stenhouse introduces study circles as a teaching method based on the critical pedagogy of learning circles (Suoranta and Moisio, 2006), which aim to develop collective social expertise. Students work in learning circles for two hours per week, and the group becomes a key medium for student learning. Learning within the group context requires students to engage with the process, which is addressed through the structure and framing of the study circles, and the assessment process.

• The Association for Learning Development in Higher Education provides resources designed to help assess and develop students’ group work skills.

A full list of references for the TILT site is available here.

Comments are closed

Comments to this thread have been closed by the post author or by an administrator.