E60 – Third Culture Dialoguing Unesco RILA

At the UNESCO RILA Spring School: The Arts of Integrating, which took place in May 2023, Scotland-based curator Dr Deirdre MacKenna and psychologist Dr Laura Cariola hosted an online panel discussion, introducing their approaches to working with culturally plural mindsets.

Through relational and interdisciplinary frameworks, these researchers have initiated a new collaboration to explore what it means to be ‘Third Culture’, and are working to activate consideration of and give voice to people who don’t define their sense of identity through a single nation-state.

For growing numbers of people, describing “where I belong” or “where I’m from” is a challenge which cannot be described simply by indicating a single location/community; their sense of constituency is formed from instances, durational periods, journeys and multiple places (both territorial and online) as well as a process of continuous resistance of the assumptions inherent within concepts of monocultural society.

This panel discussion provided a space to engage in an open, reflective interdisciplinary dialogue with a focus on the world from the perspective of Third Culture experiences, such as liminal places, belonging, and identity in-transition.

For more information about the UNESCO RILA Spring School, please visit www.gla.ac.uk/research/az/unesco…ents/springschool/

For the full show notes, including biographies of the speakers, please visit bit.ly/thesoundsofintegration

Where are you from? Raising awareness of Third Culture Students in Higher Education

Post originally published on “Teaching Matter Blog”

Where are you from? Raising awareness of Third Culture Students in Higher Education

In this extra post, Dr Laura Cariola and Tamara Lai describe the challenges faced by Third Culture Students in Higher Education, and offer suggestions on how students and members of staff can support these students. Laura is a Lecturer in Applied Psychology, and Tamara is a recent MA (Hons) graduate in Psychology and Linguistics.

Who are Third Culture Kids?

Global mobility among families and young people is becoming a common phenomenon, and the number of international migrants has grown significantly over the last 20 years. Recent figures from the United Nations (2020) suggest that there are 272 million international migrants, or 3.5% of the world’s population, living abroad. The population of dependents who accompany their parents abroad has been estimated at 31 million worldwide (UN IOM, 2020).

Within these growing statistics is a less well-known population, referred to as Third Culture Kids (TCKs), or Global Nomads. TCKs have grown up in multiple cultures and countries that are different from their parents’ or their own passport country. The label has often been associated with children who accompany parents in globally mobile employment such as members of the armed forces, missionaries or international educators, but who subsequently return to their home countries.

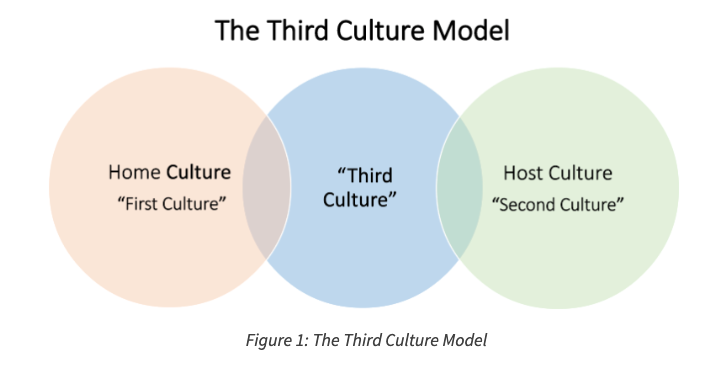

‘Third culture’ describes children who do not belong to their family’s ancestral culture (first culture or passport culture) or the host culture (second culture) in which they live, but feel a sense of belonging to all the cultures they have experienced, creating a unique third culture (see Figure 1). This third culture is not a homogenous mix between the first and second culture, but it refers to a sense of belonging with others who have similar multicultural childhood experiences rather than geographically fixed locations. As such, third culture experiences are also shared among diverse cross-cultural populations, including children of refugees and migrants.

Benefits and challenges of a mobile childhood

Psychological literature has identified various benefits of TCKs’ mobile experiences. For example, compared to their mono-cultural peers, TCKs often develop skills to adapt easily to new cultural environments, including increased open mindedness, multilinguistic abilities, and cultural empathy (Dewaele & Oudenhoven, 2009). These global perspectives and cultural resources also offer academic advantages. Due to their early experiences of living in diverse cultural and linguistic environments, and interacting with people of other cultures, TCKs often have cross-cultural competencies that are highly relevant for a globalised workforce, such as high levels of positive diversity beliefs, ability to manage uncertainty, and intercultural sensitivity (de Waal et al, 2020).

Despite these advantages, TCKs often experience various challenges. With each relocation, TCKs undergo separations from places, schools, friends, and pets they love, with many experiencing multiple losses that remain unresolved. Cycles of repeated relocations and interpersonal separations can make TCKs wary of forming close relationships to avoid further painful relational losses. Having grown up in different cultural environments, TCKs often have an unstable sense of cultural identity, and feel a sense of rootlessness and not belonging to any culture, including their home culture. Repatriated TCKs may also feel that they do not ‘fit in’ because they experience reverse culture shock and feel alienated within their own home country.Thus, it comes as no surprise that many TCKs find it challenging to answer the innocuous question “Where are you from?”, to which their answer is not a geographical location but an evolving narrative and a lifelong exploration of their sense of self and belonging in the world.

Third Culture Kids’ adjustment to Higher Education

After a childhood of cultural relocations, many TCKs relocate again when they transfer from secondary school to university. As for most students, moving to university is a time of joy but is also accompanied by challenges that come with adjusting to university life, such as culture shock and the need to orientate oneself emotionally and practically in a new academic and cultural environment. Although Third Culture Students (TCSs) are well-versed in cultural adjustments, they often struggle to adjust to university life, and nearly 40% TCSs drop out of their first institution (Ender, 2000). Unlike monocultural students, as a direct result of the multiple relational losses and unresolved grief they experienced during childhood, TCSs have difficulty forming and committing to friendships (Hervey, 2009). As such, they experience pronounced social and emotional difficulties, including feelings of loneliness, depression and anxiety.

A recent University of Edinburgh undergraduate psychology student, Miss Tamara Lai, conducted her dissertation with a focus on TCSs’ first-year experiences at university. Her qualitative analysis of five in-depth interviews identified that TCSs experience social isolation from the university’s monocultural social network due to a dislike of alcohol culture. Findings also revealed that TCSs show paradoxical social behaviour because they desire close relationships, but in order to avoid the pain of further relational losses, they refrain from emotionally investing in making new friendships. These findings indicate that unresolved grief from past relocations, accompanied by current feelings of isolation, negatively impacts TCSs’ mental health.

What are Third Culture Students’ support needs?

Although monocultural individuals might not fully understand the experience of a multicultural childhood, an accepting and non-judgmental academic environment that values diversity and inclusion is immensely helpful for TCSs’ integration to university life. There are many ways in which students and members of staff can support TCSs, for example:

1. Getting to know TCSs’ by showing an interest in and appreciation of their unique multicultural identity and their experiences of living abroad during childhood. This also means refraining from generalizations and assumptions about TCSs’ experiences based on where they have lived.

2. Acknowledging that for many TCSs, university is a place of stability after a childhood that was constantly in flux and characterised by multiple relocations. As such, university may be a time they are able, for the first time, to process their losses and unresolved grief.

3. Providing emotional and practical support to TCSs who appear to be struggling with adjusting to university life, for example, inviting them to social events where there is no ‘obligation’ to consume alcohol, and encouraging them to share their experiences with you.

4. Creating a community of belonging and a network of students with similar multicultural experiences, enabling TCSs to connect with other students from similar backgrounds who value and appreciate diversity. For example, the University of Edinburgh has an active Third Culture Student Society.

5. Recognising that TCSs’ unique characteristics and skills make them ideal role-model ‘global citizens’, who have a lot to offer to their academic community.

If you are a student or member of staff and recognise yourself as someone with third culture childhood experiences – a ‘Third Culture Kid’ – please get in contact with Dr Laura Cariola: Laura.Cariola@ed.ac.uk.

Families in Global Transition Conference 2022 March 24

Exploring the Cultural Repertoires of Adult Third Culture Kids through Multimodal Autobiographies