By Dr Paul Widdop

University of Manchester

At times like these it is worth checking the calendar. It has been quite a season for Manchester City, ending as English Premier League Champions on home soil, at the Etihad. The 1st June 2022, the symbolic start of British Summertime, will see the biggest crowd of the season gather at the Etihad. But not for the English champions, they are here to worship another cultural icon, rock n Roll star, son of Manchester, and notorious Manchester City fan Liam Gallagher.

Gallagher and Manchester City have history. Aside from the rock stars life-long love affair with the club, 26 years ago the two came together for a highly significant event in the popular cultural fabric of Manchester and Britain.

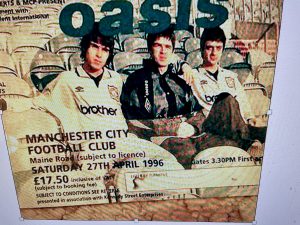

Amid the optimism of the 1990’s, in part politicised through Tony Blair’s New Labour an its Third Way, and the backdrop of Britpop, a handful of Mancunians from Burnage, a working-class suburb in South-East Manchester took to the stage at Maine Road, Manchester City’s iconic and now symbolic old stadium. On that night 26 years ago 40,000 people came to worship a coming together of music, culture and football. The five lads, Liam and Noel Gallagher, Paul ‘Bonehead’ Arthurs, Paul McGuigan, Alan White, were Oasis, the band which was the embodiment of Britpop.

It is perhaps worth reflecting on Britpop, perhaps the last significant British-based music genre and culture movement. Britpop was an ‘indie’ music scene that broke into mainstream ascendency in the mid1990s. Britpop bands, including Blur, Pulp, Suede, Elastica and Menswear, but it is Oasis that were most symbolic. Aside from the music, which reflected British rock n roll heritage, with nods to The Beatles, The Who, The Kinks and The Jam, it was the mannerisms, personalities and fashion that set Oasis apart. They had swagger, in Liam Gallagher an androgenous charismatic frontman, they were football fans, working class, and stylish. Indeed, Liam and Noel Gallagher, with influences from The Mods of the Sixties, Suedeheads of the seventies, and terrace culture of the eighties, adorned clothes that reflected the movement, they were the ringleaders of the movement. Parkas, Fred Perry polo, Retro Adidas Originals, Burberry and Ben Sherman shirts buttoned to the top, Levis jeans and Clark’s desert boots were their cloths of choice.

As Gallagher owns the stage with swagger and style at the Etihad, just outside of the stadium on Joe Mercer’s way stands the club shop, a testament to the new commercialisation of football. At present the English champions are showcasing their new kit for the coming 2022/23 campaign, nothing new in summertime, as teams up and down the country produce their marketing campaigns to accompany the new kit launches. But Manchester City, since the arrival of Adu Dhabi Investment Group, do things a little different, and they do it very well. The marketing and creatives around Manchester Cit are master practitioners of using cultural codes and nostalgia to generate a consumable past.

What is interesting is that Manchester City highlight that this kit is to celebrate iconic teams of the past and Club legend Colin Bell. This is true the kit resembles that of the 1970s with the central positing of the badge, which the legendary Number 8. wore as he graced and entertained Maine road. But it’s the other cultural codes which are fascinating. Indeed, this year the kit, its promotional material, and its advertising, takes its cultural codes from its close connection to Britpop and Britpop’s cultural icons Oasis.

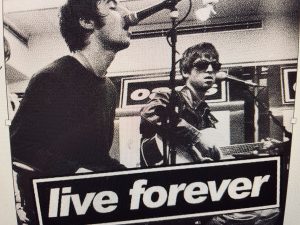

Outside the club shop projecting form its window façade is the marketing stap-line ‘Play Forever’, a clear and obvious association with Oasis’ third single ‘Live Forever’ from the debut album ‘Definitely Maybe’. Furthermore, whilst the kit is reminiscent of Bell’s City, its also very similar in style, with classic colours and trims of the t-shirts worn by members of Oasis, and its legions of followers. Furthermore, front and centre of the marketing campaign is Phil Foden, another androgenous charismatic Mancunium frontman, with a swagger. Indeed, in the marketing material Foden is mimicking the famous onstage stance, head to the side hands behind the back, made famous by Liam Gallagher.

Football loves history, revels in history. It takes us back to a different time, an escape from the world we have created. One that breaks the stranglehold of individualism and shows us another way of being a collective, of social relationships, belonging to a tribe and a city. Often nostalgia is viewed as a negative component of consumer behaviour, of a longing for the good old days, quite melancholic in its application. But football is different, fans share stories of the past, of trophy wins, of great games, of Colin Bell’s goal against Burnley. In a similar way this is also the mechanism of music movements. Subculture of music and football come together to great a powerful force of symbols (clothes, style, mannerisms), conventions and norms, a glorified past that perhaps doesn’t really reflect reality.

By tapping into collective memory, capitalism can exploit socialism, or rather socialism and the mechanisms around collective identity and belonging within a sub-cultural can be marketized and exploited to sell football kits. By associating with Oasis, with Liam Gallagher and his persona, with the cultural codes of Britpop, the Manchester City owners are using sub-cultural codes to position themselves in the marketplace. A club in touch with supporters past, of there collective history. Even those not part of the Britpop movement will recognise the signalling theory emanating form the Etihad.

It is also worth asking what City’s Abu Dhabi owners get from the club’s consumable past, apart from selling as many kits as possible to boost club revenues. It is very unlikely that the Gulf owners will recognise Oasis, Britpop, and swaggers from Mancunians. However, nostalgic soft power creates legitimacy and acceptance. By tapping into sub-cultures and its conventions they are marketizing cool, changing perceptions of out of touch overseas owners. As we have written elsewhere soft power is attractive power, a way of convincing others that you share the same values as they do and want the same things.

As the crowd at the Etihad bounce to ‘everything’s electric’, perhaps there will be more than a few in the crowd wearing the new city kit. There will be a coming together of music, football and fashion – the holy trinity’ – a powerful force. For Manchester City and its owners consumable past is an effective marketing tool for not only selling shirts, but in a wider game of legitimacy and soft power.