By Paul Widdop, Manchester Metropolitan University

Alex Bond, Leeds Metropolitan University

and Daniel Parnell, Liverpool University

All told 1900 was quite a year, as wars and industrial strikes broke out across the globe, something else was beginning to stir, the emergence of football’s royalty. As winter tightened its grip on the population of Munich, eighteen young men in a restaurant in the city district of Schwabing were plotting and forming a club, one which would become a giant; a social institution, FC Bayern Munich. From those early days in Bavaria, Bayern has witnessed an unprecedented change in the history of Europe and its Football. Germany’s most successful club now find themselves in a global arms race competing across Europe with the very elite of the game, what’s at stake in this game is the most valuable scarce resource of them all, talent. In Bayern’s 119 year history the trading place for these resources has evolved into a global capitalist economic market model, one which regulation pays little attention too.

Perhaps our story here starts at the end of this club’s current historic path, one which documents and explores how the trading market has evolved and one which captures the constant capitalist need for growth. On 19 August 2019, Bayern made perhaps the biggest transfer of the European summer window, they signed Barcelona’s Brazilian midfield playmaker Philipe Coutinho. Yet such as the market has changed, this was not a straightforward trade between the two clubs involved, it was a strategic alliance and a commitment to loan the asset on a season-long loan, which will see Bayern pay Barcelona a loan-fee of €8.5 million plus Coutinho’s wages. How have we got to these market trading conditions and what does it mean for Bayern and all clubs operating within it? This is the focus of this article.

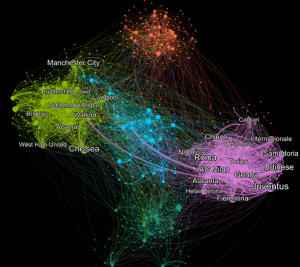

In a recent paper the Alex Bond, Paul Widdop and Dan Parnell, this loan market was explored and described, looking at its structure and trading flow. The results gave a fascinating insight into the market evolution of football and how resources flow in a market with a non-existent to limited regulation. We could say that Football is a window to a neo-classical economic view of a pure market. We have conceptualised what this market looks like, with clubs connected to others as they make loan signing alliances. In fact it looks like this.

Using data on the top-5 European leagues in European football 8139 loan transactions between 31 December 2009 and 22 December 2017 were analysed using social network analysis. Clubs are sized by their aggregate degree (number of connections to other clubs) and colour coded using a modularity algorithm (those who are more connected to each other than others). The modularity shows the natural clusters or communities loan transactions create, with each colour generally representing the countries clubs loan/borrow players to/from: light green (Premier League); pink (Serie A); orange (Bundesliga); blue (La Liga) and dark green (Ligue 1).

As illustrated, the loan system is now integral to football operations globally yet it is under-researched, which is ironic given the economic value of these trading flows. But what does all this mean. Firstly, we can conceptualise the loan system as a cross-subsidisation mechanism which distributes playing resource (assets) from one club to another. This is often advantageous to both; resource improvement/development for the giving club; better-playing resource for the receiving. Using these temporal transactions we used social network analysis to analyse the economic relations created by the loan system illustrated above.

We find several stand out points. Firstly, the loan system across Europe is embedded within some countries more than most, namely Italy. Secondly, there are ‘value creators’ (whos who often reply on loans as a talent resource) and ‘value extractors’ (those clubs who send more players out on loan to other clubs) within the loan system. Third, clearly some clubs have strategised the loan system, namely the European elite, especially Juventus. Finally, some clubs are ‘dependent’ on giving and receiving players through the loan system, therefore any regulation needs to consider unintended consequences

The practical implications of this structural account of the loan market are twofold; 1) executive-level professionals in the football industry need to understand the structure of the market within they are operating, especially as this reduces the rationality of choice, and decisions need to be made in the context of strategy; and, 2) UEFA and FIFA need to full understand the structure of the market before considering regulating it, as there may be a number of unintended consequences, especially for those ‘value creators’ who rely on loans for talent.

But what was to become of FC Bayern Munich in this interconnected future. Given their elevated status in the game, they have a rather modest loan transaction model. According to our data, over the period studied they took 4 players on loan and loaned out 22. So they traditionally haven’t been aggressive in the loan market. This is especially modest compared with Bundesliga contemporaries Bayer Leverkusen (11 loans inward and 58 outward) and Hoffenheim (10 inward and 76 outward). FC Bayern Munich have not maximised their dominant market position.

Perhaps as the Riesling was flowing on that winters day in Munich 1900, those eighteen founding fathers talked of companionship, collective action, something for the people, a foci to share ideas, to share their love of football. Whether collective thoughts wondered off to the world of Brazilian loan signings is another matter, what is clear Bayern are very much part of this modern football trading market, and what is at stake is scarce resources, talent.

Paul Widdop: p.widdop@mmu.ac.uk

Alex Bond: a.bond@leedsbeckett.ac.uk

Dan Parnell: d.parnell@liverpool.ac.uk