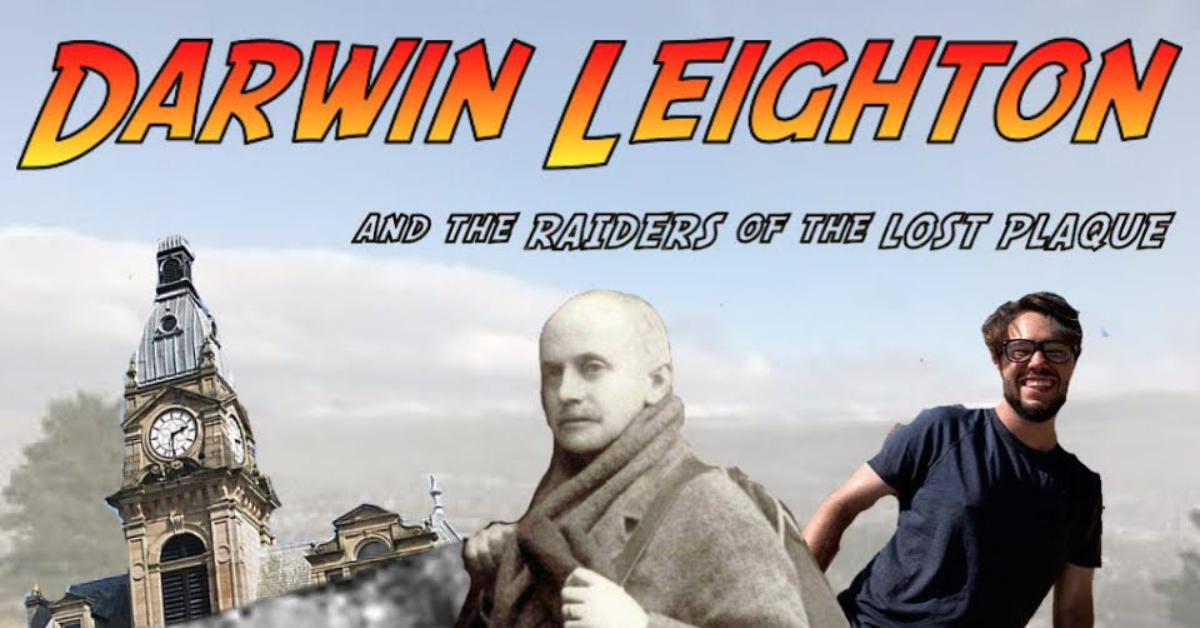

Darwin Leighton and the Raiders of the Lost Plaque

When History and Archaeology student Tom’s outreach project fell foul of Covid, he looked closer to home for inspiration and Footnotes was born.

One day in December I was trawling through reports written by the commercial archaeology firm Oxford Archaeology North about the archaeology that they had found in my local area. Commercial archaeologists survey archaeological remains on behalf of companies and governments, usually to help them make decisions about heritage preservation or building projects. Commercial archaeologists are made to work much quicker than academics, navigating strict deadlines and small budgets. Consequently, their reports are often dry lists of facts with few attempts to make them relevant or exciting to a wider audience. They are often referred to as “grey” literature. Not so that day!

Almost by accident I stumbled onto a description of a plaque dedicated to someone called Darwin Leighton. Intrigued by – if nothing else – his name, I looked him up online. It turned out he lived and died in Bleak House, Kendal. It was then that my obsession began. Why? Because Bleak House is less than 100 metres from where I live, where I am sitting right now. In fact, because my house was a bakery during Darwin’s lifetime, it’s possible he once stood in the very room I am writing in.

I just had to find the plaque. This would be an ideal story to share for the same reasons it appealed so much to me. It was local and personal, highlighting how archaeology can allow us to explore the lives of humans who lived in the same places we do and – in many ways – lived quite similar lives to us. The problem was no map was included in the original report, instead just a cryptic reference to another report. The black and white photo of a wall next to some trees was also, to put it mildly, less than illuminating. But I was on the scent and, like Lara Croft or Indiana Jones, I couldn’t be stopped. Admittedly – rather than hired guns, intricate booby traps and (sigh) dinosaur infested Aztec ruins – the challenges facing me were local bureaucracy, rain and overgrown bushes. I eventually found the second report and even a vague grid reference for the plaque. Armed with a paper printout, I strode into the woods convinced that determination, guile and grit would find the plaque. They didn’t. Hours later, I was stood on the roadside, trying to read my crude map by the light of the setting sun. Then, it struck me and all at once I understood the meaning of the map. The plaque was metres away from me. There were two paths I could take, a long route following footpaths or a much shorter route through some bushes. Seconds later, I had found it! “Archaeologists are a peculiar bunch” I thought to myself, pulling twigs out my hair.

I just had to find the plaque. This would be an ideal story to share for the same reasons it appealed so much to me. It was local and personal, highlighting how archaeology can allow us to explore the lives of humans who lived in the same places we do and – in many ways – lived quite similar lives to us. The problem was no map was included in the original report, instead just a cryptic reference to another report. The black and white photo of a wall next to some trees was also, to put it mildly, less than illuminating. But I was on the scent and, like Lara Croft or Indiana Jones, I couldn’t be stopped. Admittedly – rather than hired guns, intricate booby traps and (sigh) dinosaur infested Aztec ruins – the challenges facing me were local bureaucracy, rain and overgrown bushes. I eventually found the second report and even a vague grid reference for the plaque. Armed with a paper printout, I strode into the woods convinced that determination, guile and grit would find the plaque. They didn’t. Hours later, I was stood on the roadside, trying to read my crude map by the light of the setting sun. Then, it struck me and all at once I understood the meaning of the map. The plaque was metres away from me. There were two paths I could take, a long route following footpaths or a much shorter route through some bushes. Seconds later, I had found it! “Archaeologists are a peculiar bunch” I thought to myself, pulling twigs out my hair.

Why was I doing all of this? I was enrolled in the course Geoscience Outreach and Engagement, where each student organises their own outreach project in order to share something about our university course with the public. My original plan, a tour of Edinburgh’s archaeology, had been scuppered by the second wave of coronavirus in the UK, forcing me to return home to Kendal, Cumbria. Instead, I decided to make a series of short videos highlighting the unsung archaeology of my local area to, firstly, teach the people around me about the archaeology of my home town, and to tell stories that are deeply personal about the people who lived here in the past, many of whom were just like me. But I realised that, especially at the moment, not many of the people who watch will be able to visit Kendal so I also strive to teach broader lessons about what archaeology can teach us and how people can make their own discoveries.

Why was I doing all of this? I was enrolled in the course Geoscience Outreach and Engagement, where each student organises their own outreach project in order to share something about our university course with the public. My original plan, a tour of Edinburgh’s archaeology, had been scuppered by the second wave of coronavirus in the UK, forcing me to return home to Kendal, Cumbria. Instead, I decided to make a series of short videos highlighting the unsung archaeology of my local area to, firstly, teach the people around me about the archaeology of my home town, and to tell stories that are deeply personal about the people who lived here in the past, many of whom were just like me. But I realised that, especially at the moment, not many of the people who watch will be able to visit Kendal so I also strive to teach broader lessons about what archaeology can teach us and how people can make their own discoveries.

Four videos are now on YouTube on the Footnotes channel covering lime kilns, time guns and ridges and furrows. And Darwin Leighton, of course.

You can watch all Tom’s videos on the Footnotes channel on YouTube.