Beginning the Lacuna project

Ahead of the Lacuna project, Chloe writes about the inspiration and aims of it.

I am a Masters by Research student of History at the University of Edinburgh. In January 2025 I was awarded funding by the Student Experience Fund to develop an exhibition across the University’s campuses. This exhibition, entitled ‘Lacuna’, will be made up of multi-media art displays exploring connections between LGBT history, the city of Edinburgh, and the University of Edinburgh’s collections, including the Lothian Health Services Archive, the School of Scottish Studies Archive, and the Vere Gordon Childe Collection.

William Sharp

A lacuna is a gap, in historical sources or the body. Putting together a history of LGBT people in Scotland is to find lacuna after lacuna. Sometimes, with enough digging and investigation, individual people who expressed same-sex desire, such as Marie Maitland, or who deviated from norms of gender expression, like Walter Sholto Douglas, are found through documentary evidence. Other times, they lived out their lives openly embracing complex gender identities, as did Fiona Macleod/William Sharp. In other cases, non-consensual posthumous examination resulted in gender non-conforming individuals, such as Dr James Barry. However, these examples of individuals are rare and tend to overrepresent those who could afford to learn to write.

The exception to this is where people’s names remain as a result of persecution. Examples of people in this project, the schoolteachers Jane Pirie and Marianne Woods, went to court to clear their names when they found themselves at the centre of a scandal. Examples I have found of men accused of witchcraft include sodomy charges, which may have been as spurious as the charge of magic. Some researchers choose to approach this by refraining from using labels such as “homosexual” or “transgender” as they argue that we cannot know how people identified as the time. Furthermore, what we now call “queer” was, in other times and places, only the expression normative gender expression and sexuality.

To address this I have turned to our own archives, and the records of early pride in LGBT identity.

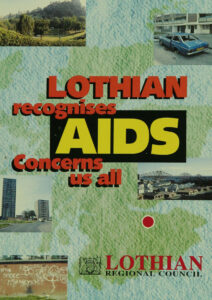

Edinburgh was disproportionately affected by the AIDS crisis, and this is reflected in the Lothian Health Services Archive. This is housed at the Centre for Research Collections, where members of the public as well as staff and students can access their collections. These archives invoke the importance of community for queer people, as community centres, newsletters, discos, and educational information were created to ensure the safety of LGBT people. This was particularly important as homosexuality was criminalised until 1981, and thereafter police frequently detained LGBT people without arresting them in a continuation of tactics which targeted the community.

|

|

|

While the most completely recorded LGBT moral panic in the University’s archives, it is certainly not the only one. In fact, LGBT people have frequently been scapegoated during times of social change and accused of corrupting the moral character of society. The canard that queer people pose a danger to children, and their association with moral decay, are present in the literal witch panic of the 17th century, as well as the case faced by Pirie and Woods. By the 1980s, the tragic prominence of gay men amongst the victims of HIV/AIDS led to their ostracisation, fears for the safety of children, and hateful rhetoric that they were experiencing God’s punishment. Underlining this history is the variation on the theme of “witch hunts”, of scapegoating those who lived differently and using criminal prosecution to damage their reputation, confine them and end their lives.

Finally, it is worth lingering on the difficulties of finding transgender people in historical sources. People “cross-dress” for a variety of reasons, and so the motivations of gender-non-conforming people are not always clear; cross-dressing might occur as people recorded as women seek better wages in male jobs, to pursue other women romantically in the guise of men, to work and travel in the military, or to perform on the stage. Mainstream society records these people, often in newspaper reports, with curiosity, humour, sympathy, intrigue or a desire to shame them. While troubling, these responses are varied in tone and speak to the complexities of the past. In the University of Edinburgh’s own archives, similar stories exist as folk songs which I have used as another inspiration for this project. Elliot Holmes, a member of staff working at the Centre for Research Collections, has written on the use of queer theory when using these as sources for queer histories, taking into account the problematic nature of their creation. One theme which I look forward to returning to here is shape-shifting in Scottish ballads, as collected at the School of Scottish Studies Archives.

Yet for all of the difficulties which LGBT people have faced, our community has been founded on care and acceptance. The Lothian Health Services Archive is a testament to the importance of a collective voice when we advocate for our community. The famous poster Silence=Death, created by the Silence=Death Project consciousness-raising group in 1985, speaks to the importance of speaking up for ourselves as our rights remain a device of political division. By drawing on the wisdom of queer elders who experienced the onset of the AIDS crisis, I want to shine a light on the varied history of LGBT people in Edinburgh.

(By Unknown author - http://fred-de-vries.blogspot.com/2016/08/review-dr-james-barry-woman-ahead-of.html from Museum Africa, Johannesburg, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=87253849)

(public domain )